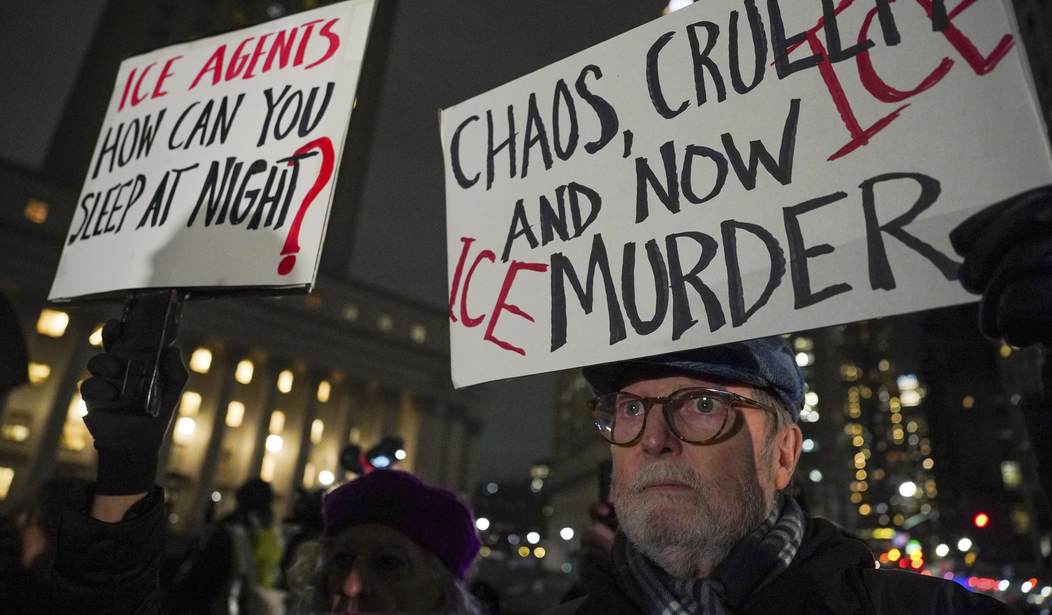

To say that several American cities are now seeing serious unrest, even open defiance of lawfully constituted authority, is something of an understatement. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents are being openly challenged by increasingly angry and unhinged mobs in the course of carrying out their statutory duty, enforcing the nation's legally constituted immigration laws.

Minneapolis, at the moment, seems to be the Schwerpunkt of this increasingly strident rebellion, and no, I don't think rebellion is too strong a word for it. So, what can the federal government, specifically the Trump administration, do about it?

On Thursday, I examined the Insurrection Act, how it works, how it has been used in the past, and whether it might apply now:

Read More: When Presidents Unleash the Insurrection Act - and Why It Matters

Now, let's discuss the ultimate application: martial law.

First of all, let's dispense with the notion of a national application of martial law, which has in recent years been the topic of a lot of blog posts and news stories. A nationwide declaration of martial law is not only unlikely in the extreme, but it would be impossible to enforce; here's why, and I'm going to tell you.

A blanket declaration of martial law is logistically and tactically impossible in a nation the size of the United States. Even if we were to assume that the entire U.S. military and law enforcement communities were to agree, without argument or dissent, to enforce the declaration, our armed forces and civil police forces combined are insufficient to hold down 80-100 million (that's likely an underestimation) armed citizens, many of whom are military veterans (myself included). And it is unlikely beyond belief that the military and law-enforcement communities would unquestioningly obey such a declaration. There would almost certainly be massive disobedience, if not outright rebellion, among the nation’s military members, a majority of whom hold no fondness for the leftist rioters in cities like Minneapolis.

The United States has 4 million square miles of land, 4 million miles of paved roads, 150,000 miles of railroads, and thousands of miles of navigable rivers. There is no conceivable way that any government could monitor, much less control, all of the movement of citizens along those routes. The only result of such an effort would be massive civil disobedience and the rise of a massive black market for all manner of goods.

An effective enforcement of martial law would require the federal government to shut down the internet and cell phone networks. This would cause untold chaos in every aspect of life, but most notably in the business world. The vast majority of American businesses rely heavily on the internet and cell phone networks for everything from accepting credit/debit card payments to coordinating operations. This action would plunge the economy into a depression that would make the 1928-1941 depression look like a picnic, and the impact would be global; despite the best efforts of the government, the United States is still far and away the most powerful and influential economy on the planet.

No, no administration, Democrat or Republican, could make that work. But a local declaration of martial law? Say, in a city? That's a different story, and it's been done several times in our nation's history. Here are a few key examples:

In 1862, President Abraham Lincoln declared martial law at the federal level at the onset of the American Civil War.

Rather than declaring martial law over a particular area, Proclamation 94 applied martial law to “all rebels and insurgents, their aiders and abettors, within the United States, and all persons discouraging volunteer enlistments, resisting militia draft or guilty of any disloyal practice affording aid and comfort to rebels against the authority of the United States.”

In 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt declared martial law in the Territory of Hawaii after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Martial law was in place in Hawaii until October of 1944.

But there are a couple of more relevant instances in which martial law was declared in response to a rebellion or uprising.

In 1921, Army General Charles Barrett declared martial law in the city of Tulsa, Oklahoma, in response to the Tulsa Race Massacre.

In 1943, Texas Acting Governor A.M. Aikin Jr. declared martial law over the city of Beaumont, Texas, for five days, in response to the Beaumont Race Riot. This declaration, among other things, resulted in civilian infractions being examined by a military tribunal, although cases were referred to civil authorities.

In 1963, Maryland Governor J. Millard Tawes declared martial law for over a year in response to riots in Cambridge, Maryland.

So, this is a tool that has been used in the past by presidents, by governors, and by military officers in response to domestic unrest. It's a tool that is available in the case of an open insurrection, as defined in the Insurrection Act.

Read More: 'Leave My People Alone': Unraveling Walz Whines After FBI Takes Over ICE Shooting Investigation

Here's the thing: The Constitution does not define martial law, nor does it clearly state who may impose it.

Throughout American history, the federal and state governments have declared martial law over 60 times. The Constitution of the United States does not define martial law and is silent as to who can impose it. However, the modern interpretation allows the president and state officials to declare "degrees of martial law in specific circumstances."

Some scholars believe the president has the executive power to declare martial law. Others believe the president needs congressional authorization to impose martial law in a civilian area. Therefore, Congress may be the only governmental branch that can legally declare martial law, and the president can only act according to its action.

It's an interesting problem. Which takes us back to Minneapolis.

Now, Governor Tim Walz (D) isn't about to declare martial law, not under any circumstances; that much is certain. And while President Trump could make an argument, especially if he invokes the Insurrection Act, that he has the right and the power to declare martial law in the city of Minneapolis, such a declaration would no doubt be blocked by the first tame judge that the opposition could stir up; more than anything else, this would lead to yet another protracted legal battle.

At the moment, President Trump hasn't shown any inclination to invoke the Insurrection Act, much less make a declaration of martial law. But the laws on the books and the history of this tool should render it a last-ditch attempt to restore order in the face of open rebellion. But the problem is that the city of Minneapolis, along with some other Democrat-dominated cities, like, say, Portland, Oregon, may well be approaching that point.