I had a personal mantra as a newspaper correspondent some years ago. If I was where other reporters were, then I was most likely in the wrong place.

I did not always succeed in that goal. There was much routine stuff that my editors felt needed covering – politics, tornadoes, diplomacy, economics, small-town shootings. And did I mention politics?

This is another in the ongoing series of Memories (links to all the others are below) from my journalism and political career and life, which thankfully is also ongoing.

I always wanted to report and then write unique stories, unusual tales that felt different, about interesting people and details, curious, offbeat things readers might not know they wanted to know. After a while, I got a reputation for that, which explains a phone call I received from the U.S. Coast Guard.

Every spring, that service flies patrols out of Newfoundland to track and report on the gigantic icebergs that break off of Greenland and start their slow drift south to eventual extinction in the warmer waters of the Gulf Stream.

Those frozen monsters contain thousands, even millions of tons of accumulated snow that fell, compacted, and slowly slid toward the Greenland coast in valley-wide sheets of ice. They are so immense you can feel their chill a mile away.

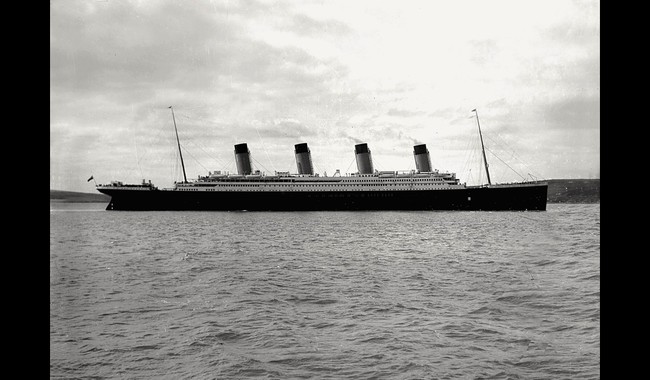

Largely submerged, until radar, they were also very hard to spot after sunset, especially when the sea was calm, as it was on the historic night of April 14-15, 1912.

Sixty-two-year-old Edward T. Smith was given the honor of captaining the White Star Line’s new RMS Titanic on her maiden voyage from Southampton to New York. An excellent raconteur with a tidy white beard, Smith was very popular among passengers for his engaging personality and sea tales stretching back into the 1800s.

On the fifth and fateful night of the voyage, about 1,200 miles northeast of New York City, radio traffic was full of iceberg reports. One ship, the Californian, found the ice packs so daunting that its captain simply ordered "All Stop" to await dawn and avoid the risk of running into hidden icebergs.

Titanic's Marconi radio operators relayed most, but fatefully not all, messages to the bridge where the deck officer altered course slightly to the south. For unknown reasons, the Californian's decision somehow did not make it to the bridge.

The Titanic seems minuscule today, but in her day was mammoth — 883 feet long, 93 feet wide, 65,000 tons, built for luxury. Some cruise ships today are nearly four football fields long and displace 228,000 tons with upwards of 9,000 crew and passengers.

Titanic had 16 compartments that could be closed from the bridge. Her builders claimed four compartments could be breached without danger, which, they said, made the ship unsinkable. The compartment bulkheads, however, were not sealed at the top.

Standing about 145 feet above the water, the Titanic's lookouts were Frederick Fleet and Reginald Lee. They were hampered that night because, for some reason, the crow's nest binoculars were missing.

What might not have happened had the instrument been there?

As one result, the lookouts did not see the iceberg in the frigid, North Atlantic darkness until it was too late. The waters were calm, so there were no telltale ripples and whitecaps to betray an iceberg's presence.

The helmsman desperately signaled to reverse the three giant propellers and frantically spun the wheel to turn the 100-ton rudder and avoid the looming collision.

Unfortunately, he almost succeeded.

Had the brand-new Titanic hit the iceberg head-on at 22 knots, it likely would have survived. But nearly missing it proved fatal.

Like icebergs, much of the ship's bulk was beneath the waterline, an almost 35-foot draft. The starboard side scraped relentlessly against the unyielding, centuries-old ice. The hull was made of one-inch-thick steel plates. But the iceberg gashed large openings along at least five compartments as if the steel was wet bread.

Water gushed in to fill the compartments. With no bulkhead caps, the seawater spilled into the next compartment one after another. The ship's bow began to tilt down. As each compartment filled, Titanic tilted more, inviting water into additional compartments.

Distress signals went out and several ships responded, but they were hours away. The Californian was much closer, idling until sunrise. But it had turned off its radio.

Two hours and forty minutes later, with the orchestra still trying to play on deck, the ship slid into the black water on her ponderous plummet nearly two-and-a-half miles down to a muddy tomb. The bow section landed with such force it forged a 60-foot crater.

There, split in half, she would lie alone in darkness for 73 years.

Being so obviously unsinkable, the Titanic had set sail with only 20 lifeboats, nowhere near enough for the 2,227 people onboard. And, fearing cable jams, some crew members hastily launched lifeboats only partially full.

Naval veteran Capt. Smith was on his final voyage before retirement. His last reported words to the crew were: "Boys, do your best for the women and children, and look out for yourselves."

He was last seen making his way back to the bridge to go down with the ship, along with 1,517 others.

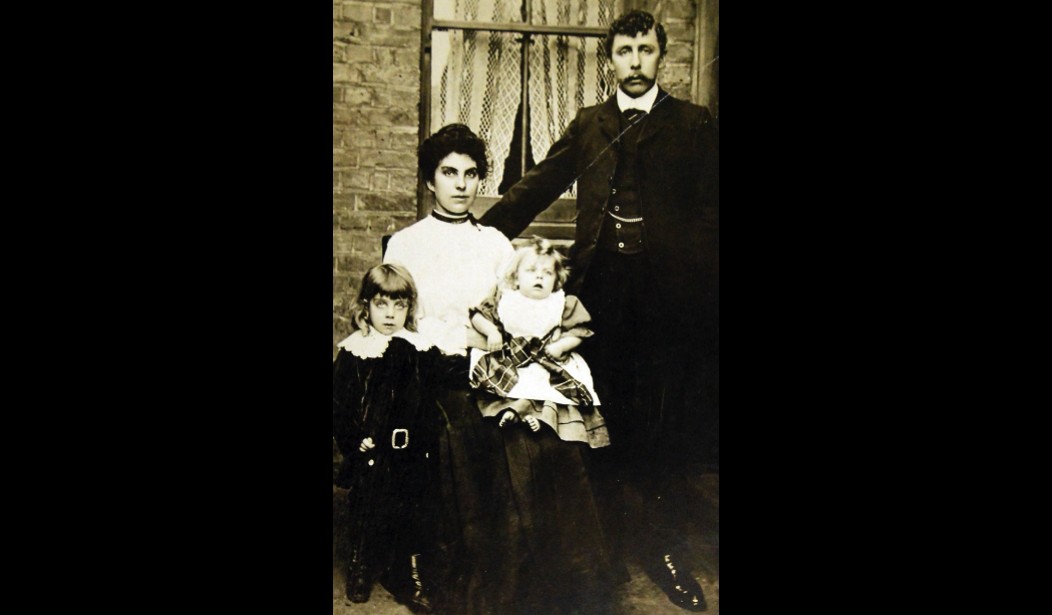

One of those fatalities was Frank Goldsmith, a British lathe operator who had saved $30 to transport his wife and son to the United States, where he heard jobs were plentiful.

As the ship's compartments filled with water, one by one, Frank Goldsmith stood with his family on the titling deck near one of the last lifeboats. He hugged his wife, Emily. Then, he leaned down and squeezed the shoulders of his four-year-old son.

“So long, Franky,” he said. “See you later.”

Not long after, as the Titanic vainly fired her final flares, Franky’s Mom covered his face as the new ship slid from sight.

His father's last words were embedded in the youngster’s mind.

Franky went on to lead a largely happy life, first in Michigan, where he coached church basketball, then Ohio, and a Florida retirement. He married Victoria in 1926. They ran a photography supplies store in Ohio for years and had three boys, 11 grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren.

About this time every year, his widow told me, Franky would grow eerily silent for days, especially if he heard the screams of sports crowds drifting from a nearby stadium.

Sometimes, he’d feel compelled to retell his memory of that night and Victoria would listen patiently, though she knew the details by heart.

Word of Goldsmith’s stories spread. In the mid-sixties, a Rotary Club asked him to share. “At first,” his widow recalled, “it was very painful for him. But the more he talked, the easier it became. He told the story so well.”

The mid-April silences soon became busy times for public recollections. One year, Victoria Goldsmith recalled, he did 13 radio interviews in one day.

In 1970, Franky Goldsmith had a stroke. But nothing could erase his memories of 1912. He was excited early in January of 1982 when the invitation arrived to address the Titanic Society in April.

That night he stayed up to watch the TV news. Around midnight, Victoria found him gone on the couch.

But she knew precisely what he wanted. For some 30 years he said he wanted to rejoin his father at the Titanic.

Over the ensuing weeks, Victoria Goldsmith was in touch with a long series of kind people in Massachusetts, New York, North Carolina, and Florida.

Every April 15, the Coast Guard flew over the recorded location of the Titanic and dropped a wreath. The ship’s precise resting place would not be found until 1985, some distance away.

But in 1982, a small box containing Franky Goldsmith’s ashes was held tightly in the hands of Petty Officer John Flynn in the back of a Coast Guard iceberg patrol plane. I was there, too. Everyone wore helmets and was strapped on a secure leash as the plane’s back ramp lowered slowly.

Immediately, a bitter, wild wind swirled inside the plane, sucking out anything loose and making the leash amply appreciated.

A thousand feet below, through wispy clouds, I could see the dark-grey waters of the North Atlantic spotted with wind-whipped white caps.

Coast Guardsman Flynn, who knew little of Franky Goldsmith's story, crept closer to the edge. When the pilot hit the green light some 400 miles south of Newfoundland, Flynn launched the annual wreath into the slipstream. Then, he opened the little box and turned it upside down.

Maybe three handfuls of granular ashes blew out the back to be instantly absorbed by the winds and fall into the frigid water below. Minutes later, Frank Goldsmith’s promise from 70 years before was fulfilled: “So long, Franky. See you later.”

Upon landing a few hours later back at Gander, Newfoundland, I phoned Victoria Goldsmith to describe the afternoon in detail. “For all his life,” she said, “April 15th was very sad for him. But that will be different now. They are back together.”

Postscript:

Before the aircraft's rear ramp slowly closed that afternoon 40 years ago today, I tossed out a plastic Diet Pepsi bottle containing two of my business cards. But that’s another Memory.

This is the 15th in an occasional series of personal Memories. The others are below. I hope they trigger your own memories to share in the Comments.

Things My Father Said: 'Here It's Not Loaded'

The Terrifyingly Wonderful Day I Drove an Indy Car

When I Went on Henry Kissinger's Honeymoon

When Grandma Arrived for That Holiday Visit

Practicing Journalism the Old-Fashioned Way

When Hal Holbrook Took a Day to Tutor a Teen on Art

The Night I Met Saturn That Changed My Life

High School Was Hard for Me, Until That One Evening

When Dad Died, He left a Haunting Message That Reemerged Just Now

My Father's Sly Trick About Smoking That Saved My Life

His Name Was Edgar. Not Ed. Not Eddie. But Edgar.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member