When I was a little boy, I waited in a very long line with my father to inch our way slowly along a leaf-strewn sidewalk into an observatory in Cleveland.

My feet were bored. But I knew it must be an important occasion because we never did anything like that on a school night.

Eventually, we got inside. Then, step by step up several floors into a cavernous room with the roof open. When my turn came, Dad lifted me up on a chair to look through a tiny viewer on a huge telescope.

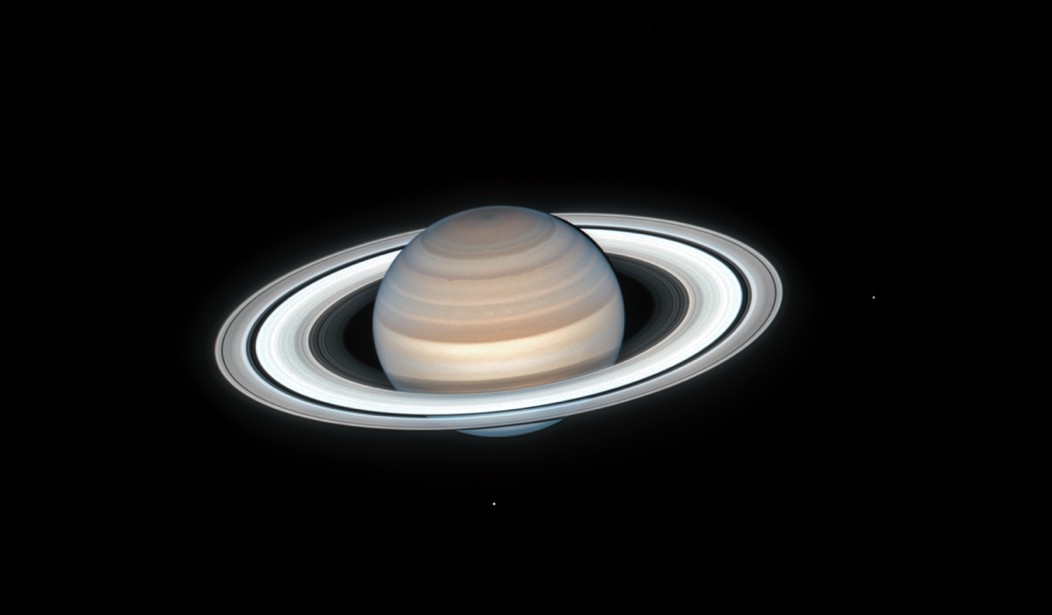

It was Saturn!

I had never seen anything so big, so mysterious, so strangely beautiful. Filling the lens was an immense, brilliant white orb, tilted, with silver, white, and black rings of dust precisely encircling its middle. Just hanging there in the boundless black of Space. It seemed so close you could almost touch it. Yet Space stretched beyond comprehension. It still does.

The astronomer said Saturn that night was 822 million miles away. I wasn’t in kindergarten yet. So, my world was measured in city blocks. I had no idea what a million anything was. But if it was farther than crossing Pennsylvania in the backseat of a Plymouth, I knew that was a long ways.

Those 15 seconds shaped my life. Not in terms of career choice. I’m fine staying right here on the surface of Earth, or within 35,000 feet of it. I knew our planet was orbiting the Sun. I did not realize that on that journey, in addition to rotating at 500 miles an hour, Earth is moving through Space eight miles every second.

Astronomy, I was told, involved a lot of arithmetic, which led to long division and fractions and, God help us, Algebra. Two years, to be honest.

What made me jabber all the way home that night and all the way upstairs and into bed was the scale of Space. Big was too small a word. Even immense was inadequate. I’ve got some more things about that to share with you.

Awesome is a word that’s been much abused in modern life. Awesome is not a jumbo tub of movie popcorn.

Like ants, many of us rarely look up as we scurry about. We should. Awesome is peering into the night sky and spotting the three stars of the Alpha Centauri system, the “closest” stars after our Sun.

By close, I mean “only” 4.24 light years away. Traveling at the speed of light, which is 186,000 miles per second, the Alpha Centauri light beam that reaches your eyes tonight has been traveling to your retina since Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris burned down.

That journey to Earth at the speed of light covered almost 25 trillion miles, much farther than even crossing Pennsylvania twice.

Space and the real meaning of that is on my mind again these days because this is what’s scheduled to happen early Sunday morning: A capsule launched from Florida by NASA seven years ago will complete an epic return-space journey by parachuting into the Utah desert. NASA TV will cover the return.

Inside the capsule are a couple scoops of asteroid gravel from the Big Bang when the universe was created nearly 14 billion Earth years ago.

The asteroid named Bennu is one of millions, some of which crashed into Earth over time, depositing the building blocks of life.

Some 66 million years ago, long before Joe Biden's birth, an asteroid about six miles wide crashed near Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula, creating a crater 10 miles deep and a global earthquake that lasted weeks.

The impact and catastrophic debris cloud ended much of life on Earth, including about 1,000 species of dinosaurs, every single one of them except those that Steven Spielberg discovered.

Bennu is just a little guy by galactic standards, some 1,700 feet in diameter, weightless in the vacuum of Space but an estimated 171 billion pounds if it was on Earth.

A potato-shaped chunk of space debris, Bennu has been flying around out there for billions of years, waiting for scientists at the University of Arizona to develop a robot that could be launched into Space, directed to find then catch up to that rock more than 100 million miles away, circle it for a year’s study, land on it gently, scoop up some of whatever is there, take off, loiter nearby for a while, then begin its on-time delivery to Utah two years later. That's all.

The robot itself will not be landing, however. It’s heading off to study another passing asteroid six years from now.

As you can see, not much to be impressed with in Space this week.

The long-ago night I experienced Saturn led to building a little tube-telescope with Dad, drawing star maps, and watching fake space shows like "Captain Video" and "Tom Corbett, Space Cadet." Years later, I looked up Saturn. I was right. It is big, very big -- more than 870 Earths would fit inside.

A couple years after the observatory visit, an Air Force officer named Chuck Yeager flew an airplane faster than the speed of sound. That, to me, was beyond imagination.

Later, I witnessed an Air Force Thunderbird F-16 silently flash by faster than sound. Two seconds later, the following roar shook my chest.

During one high school study hall, they played the beeping sound of Sputnik on the loudspeaker. I didn’t get much done that hour.

The U.S. space program began with a lot of explosions, rockets that didn’t even get six inches off the pad.

Sputnik was 10 years after Yeager’s flight. Just 12 years after Sputnik, I was a reporter at Kennedy Airport beneath a Jumbotron, interrupting people for their impressions as they tried to watch and listen to Neil Armstrong step on the Moon. Breaking News: Everyone was impressed.

I’ve flown on many 747’s. But I’m one of those people who sees no possible way an airplane weighing more than 735,000 pounds can get off the ground. Same with modern rockets.

I watched the Space Shuttle program with fascination, pride, and, at times, sorrow. In 2011, a kindly editor, knowing how I’d watched so many rocket launches on TV since high school, assigned me to cover the final shuttle flight to the International Space Station, STS 135 Atlantis, from the Kennedy Space Center.

When the engines ignited, giant clouds of steam billowed around the tower as the heat blast vaporized tons of water designed not to cool, but to muffle the massive sounds of the shuttle’s engines and two solid-fuel boosters that nearly toppled the first shuttle flight.

Six seconds after ignition, the clamps released, and the 4.4-million-pound shuttle with a 65,000-pound payload began to ascend, using the shuttle’s own engines and two solid-fuel boosters. Here’s what that sounds like.

As an astronaut told me, “Once you light those candles, hang on, ‘cause you’re going somewhere.” For 120 seconds before falling away, each booster burns five tons of powdered aluminum and ammonium perchlorate per second.

I was standing three miles from the pad at that time. When Atlantis cleared the tower, I felt heat on my face.

Now, you can get alerts when the International Space Station flies over your house.

NASA and JPL have designed, built, launched, and landed other robots wandering our solar system and the surface of Mars. Don’t forget the Hubble and Webb Space Telescopes that can literally peer back in time through our ever-expanding universe. And even let us hear space sounds.

Then, there’s the valiant Voyager twins that have fascinated me since they launched in 1977. They did revealing flyby photography of various planets on their way to become the first man-made objects to leave this solar system.

Voyager 2 is now 12 billion miles from home, pulling away another 35,000 miles every hour, piercing the exotic vacuum of interstellar space headed for no one knows where. Forever.

Yet every day, Vger dutifully phones home to a giant dish in southern California that's two-thirds the size of a football field. I visited there once and heard the faint electronic burbling of an incoming Voyager message.

Those Voyager signals take almost 18 hours to reach Earth, traveling at 186,000 miles per second. And 18 more hours to send back an acknowledgment.

Our nation and its partners have accomplished some truly amazing things in just this one lifetime. I try to remember that amid all the complaining. This was just a sampling.

This entire space Memory of mine, all 76 years of it, began as I waited with my father in a long line on a school night for the first encounter with the magic aura of Saturn. My feet were bored.

But as you may have gathered from this ongoing Memory about Space, my mind never was. I hope now yours isn't either. Comments are open below.

PREVIOUS MEMORIES:

When Dad Died, He left a Haunting Message That Reemerged Just Now

My Father's Sly Trick About Smoking That Saved My Life

His Name Was Edgar. Not Ed. Not Eddie. But Edgar.

My Encounters With Famous People and Someone Else

The July 4th I Saw More Fireworks Than Anyone Ever

Editor's Note: A previous version of this article referenced Voyager's mission beginning in 1967 rather than 1977. We apologize to our readers for the error.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member