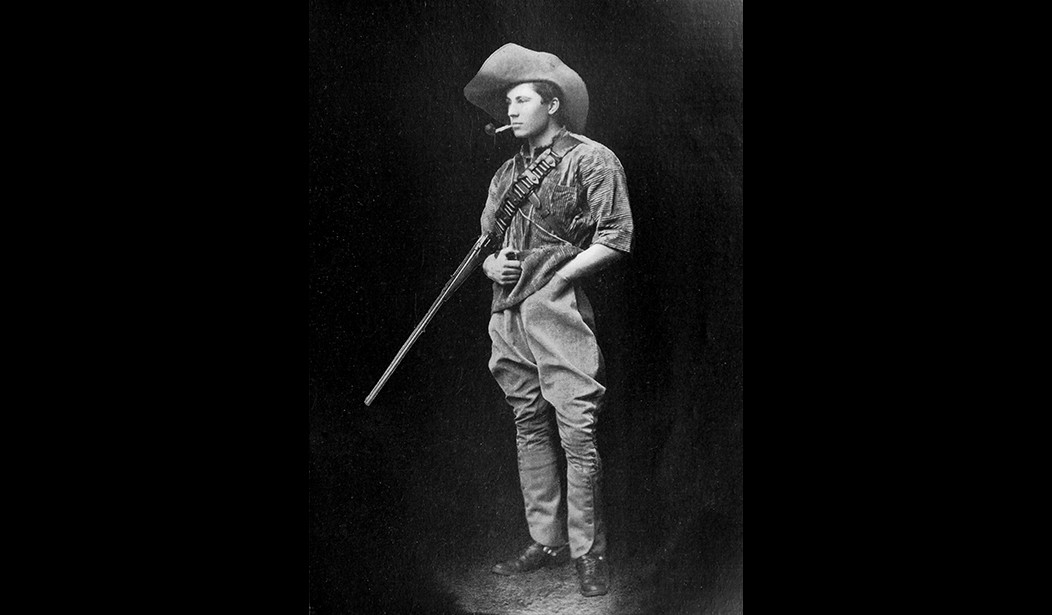

Appearances Can Be Deceiving

See the fellow in the image above? He doesn’t look like anyone very unusual; just a steady, solid young Britisher, probably a stolid fellow of no great imagination, not one to take on anything that’s not sensible. He looks like he has just left his silk-sheeted bed, downed a pink gin and a fine breakfast, and is ready to essay forth for a bit of sport.

That assessment couldn’t be farther from the truth. This is in fact the young man who would become Colonel Ewart Scott Grogan, the first man to walk the length of Africa from Cape Town to Cairo, possessor of an enormous set of solid titanium masculine appendages, and undeniably a British hero.

Origins

Ewart Scott Grogan was born in London in 1874, the fourteenth of twenty-one children of the Irish Surveyor-General of the Duchy of Lancaster, William Grogan. Young Ewart drew his unusual given name from his godfather, one William Ewart Gladstone. Once his appellation was firmly in place, he set about his career by quickly being expelled from several schools and then universities. The last of these was the famous Cambridge, where he was expelled for herding a flock of sheep into the rooms of one of his instructors. With his educational career behind him, he alleviated his boredom at nineteen years of age by first climbing the Matterhorn, then deciding to go off to Cape Town to enlist in the Chartered Company of South Africa to fight in the Second Matabele War. During this campaign, young Grogan developed a capacity for endurance of terrible hardship, having been at times forced to subsist on the flesh of mules and vultures while witnessing horrific massacres of the type not all that uncommon in tribal Africa of that time.

But it was his adventure after that war that was to earn him worldwide fame – or, at least, notoriety.

His Adventurous Career

After the Second Matabele War, Grogan found himself back in Cape Town, 24 years of age, and anxious for whatever opportunities would present themselves. While in Cape Town he fell madly in love with one Gertrude Watt, the sister of a Cambridge classmate. Unfortunately for Grogan, the girl’s stepfather disapproved of him; while he was the product of a good family, young Grogan seemed to have little to recommend him besides empty pockets and a thirst for adventure. So, Grogan made a proposal to Miss Watt’s stepfather; one might imagine the conversation went something like this:

“Young man, I just don’t see how you would make an acceptable match for my stepdaughter. Gertrude is a fine girl from a fine family and wants a solid, respectable man of character to care for her.”

“Sir,” Grogan replies, “it seems to me that I must prove that I am in fact a man of determination and character. Therefore, I propose to become the first man to walk the length of Africa, from here in Cape Town to Cairo. Will that prove my character sufficiently?”

“Well, yes, that may do.” And secretly, to himself, the old man likely thought, that impudent young pup will be food for jackals within a fortnight.

But Ewart Grogan was made of sterner stuff. In 1897, aged twenty-two, Grogan set out. He had already marched from South Africa to Mozambique during his military service, and so considered that portion of the journey a fait accompli, but with a partner, a double rifle, some native porters, and plenty of ammo, he set out to accomplish the rest of the feat. He had a five-thousand-mile hike yet to complete.

I highly recommend Grogan’s book on the journey, “From the Cape to Cairo: The First Traverse of Africa from South to North.” It’s a great narrative of the epic journey, detailing their hardships, their slaughter of all manner of wildlife virtually over the entire trek, and their day-to-day travels. They evaded predators ranging from lions to crocodiles and contended with malaria and dysentery. The journey, eschewing straight-line travel and choosing instead to wander widely, covered all manner of terrain. They crossed deserts, hiked through savannahs, traversed the Great Rift Valley. They detoured around swamps, volcanoes, and tribes of native warriors.

In an unusual act for the time, Grogan carried a supply of trade goods and currency and purchased supplies from local people along the route instead of merely confiscating them as many European explorers were wont to do when dealing with native villages. Probably at least in part because of this, they had little trouble with the locals, aside from the odd band of warriors and one tribe of cannibals who pursued the party through a portion of the Congo.

After two and a half years, the battered and exhausted Grogan emerged at the upper reaches of the Nile, there to encounter a British medical officer named Captain Dunn, who was leading a small exploratory party. Dunn was understandably surprised to see a bedraggled young British chap emerge from this howling wilderness, and the conversation that followed was a masterpiece of British understatement:

Dunn: “How do you do?”

Grogan: “Oh, very fit, thanks; how are you? Had any sport?”

Dunn: “Oh, pretty fair. But there’s nothing much here. Have a drink? You must be hungry; I’ll hurry on lunch.”

Grogan returned to England in triumph. He was then twenty-six and was promptly feted by London society, made a fellow of the Royal Geographic Society, and was rewarded further with an audience with Queen Victoria. After publishing the book mentioned above to international acclaim, he capped his successes by returning to Cape Town and, after accepting the astonished congratulations of his soon-to-be-father-in-law, marrying young Gertrude.

But he had more adventure in him. Grogan was not yet thirty and had no expectations of easing himself into any kind of settled life.

See Related: Portrait of a British Hero: John Malcolm Thorpe Fleming 'Mad Jack' Churchill

Portrait of a Scottish Hero: Walter Dalrymple Maitland 'Karamojo' Bell

His One-Man War

It’s not commonly known to people who haven’t seen "The African Queen" that the Great War had an African theater.

The outbreak of the war found Grogan with his wife Gertrude in Kenya, where to stave off boredom he built that nation’s first deep-water port at Mombasa, opened a successful Nairobi hotel called “Torr’s,” opened Kenya’s first dedicated children’s hospital, and kick-started Kenya’s timber industry.

When war was declared, Grogan quickly volunteered. While details on his wartime service are unclear, it is known that he fought in several battles in German East Africa, eventually attaining the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and receiving a Distinguished Service Order and three mentions in citations. Slaughtering Germans was at least as interesting as slaughtering wildlife, and his talent for un-aliving German troops earned him the nickname of “Bwana Chui” (the Leopard) from the local Kikuyu tribesmen.

There was, however, a less pleasant and accommodating side to the man.

His Dark Side

The first recorded instance of Ewart Grogan results from the “Nairobi Incident” of 1907. Ewart Grogan was not a man to cross; when three rickshaw drivers were “impudent” to his sister and her companion, Grogan and a couple of friends tracked the errant drivers down and administered what the Brits would call “a damned good thrashing” in the public square. One of the drivers was badly injured and required hospitalization. The judge demanded to know why Grogan had reacted so violently and was answered with, “Because I wanted to.” Unimpressed, the judge sentenced Grogan to a month in jail.

During the Great War, Grogan spent some time in hospital with blackwater fever. During his stay, he was not so incapacitated that he was unable to seduce a nurse 26 years his junior nor to father an illegitimate daughter. Later in the war, he repeated this feat, albeit his second mistress was only 16 years younger.

Later in his life, Grogan vocally advocated the seizure of lands from native Africans, claiming that they were “…inferior in mental development and ethical possibilities.”

But, like all of us, Grogan was a product of his time. His violent temper was generally unacceptable even in his era, as his jail sentence demonstrates; his racism, on the other hand, was a prevalent view among most Europeans of the time. Whatever Grogan’s bad traits, his courage and fortitude were still remarkable, even by the standards of his somewhat more adventurous time.

His Golden Years

Despite his stated disdain for the intellectual capacities of native Africans, in his later years, Grogan devoted a considerable amount of time and resources to their benefit. While serving on the Colonial Association, he took an interest in improving educational opportunities for the natives, claiming that “…the road of achievement must be open to all Africans, as only then could a reasonable and decent society in Africa be achieved.”

During the Second World War, Grogan, then in his sixties, reported to the nearest British Army outpost in Nairobi and aided in carrying out reconnaissance missions across the Congolese border. Eventually, he was placed in charge of three prisoner-of-war camps, a duty which he held until the war’s end.

After the war, he returned to Nairobi in sadness, as his wife Gertrude had died suddenly of a heart attack in 1943. In happier times Grogan had built her a substantial house in Nairobi, and as a memorial to his wife, Grogan donated the house to be refitted as the Gertrude’s Garden Children’s Hospital. There are today seven branches of this hospital in Nairobi; this, perhaps, is the most lasting and successful portion of Grogan’s legacy.

Ewart Grogan eventually remarried one Camilla Towers and divided his time between Nairobi and Cape Town. He died in the latter city in 1967, aged ninety-two.

Few men in history can match Ewart Scott Grogan in determination, raw courage, fierce single-mindedness, in utter fearlessness. His is a type that the British no longer produce, and that’s a sad note. But Grogan holds a singular place in the history of his countrymen; his longtime friend Rudyard Kipling may well have been writing of Grogan in his poem How To Be A Man:

If you can fill the unforgiving minute

With sixty seconds’ worth of distance run –

Yours is the Earth and everything that’s in it,

And – which is more – you’ll be a Man my son!