Every war produces a few battles which serve as axioms for that conflict. In my view, the American Revolution produced two battles which really let you understand the war. The first of these is the rapid fire combination of First Trenton, Second Trenton, and Princeton between December 26, 1776 and January 3, 1777. Here you see the first glimmer of Washington as a strategist in addition to being a battlefield leader. During the retreat into Pennsylvania, Washington had all the boats on the New Jersey side of the Delaware River rounded up and consolidated on the Pennsylvania side. This stopped the British advance in its tracks and also showed that even in retreat, Washington was anticipating offensive action. At second Trenton, and during the ensuing Forage War, it became clear that the American army was learning how to integrate militia into its scheme of maneuver, not as an an ersatz unit of the infantry line but as a special tool in its own right.

The second, and my favorite, is Monmouth. While the official Army birthday is June 14, 1775, I would argue that the US Army was conceived in 1775, gestated at Valley Forge during the winter of 1777-1778 and born at Monmouth Courthhouse, New Jersey on June 28, 1778.

On February 6, 1778, the United States and France signed a military alliance. The British Army in North America, under General Sir Henry Clinton, was ordered to send substantial numbers of his army to defend West Florida against Spain, who had also entered the war, and the West Indies against French attacks. Clinton was located in Philadelphia and this loss of forces dictated that not only should Philadelphia be abandoned but that British forces would fall back onto the Loyalist stronghold of New York City (funny out some things remain constants, isn’t it?). There weren’t sufficient ships to evacuate Philadelphia loyalists and the British Army so most of the British troops were forced to march back to New York.

The winter of 1777-1778 had been difficult and rewarding for the American army. The privations of Valley Forge had welded a cohesion that had been lacking and the arrival of the Prussian drillmaster, Friedrich von Steuben, had produced trained troops and the beginning of a corps of noncommissioned officers. Washington, ever eager for offensive action, was fairly champing at the bit. According to the custom of the time, Washington held a council of war. Most of the younger generals and regimental commanders wanted to strike Clinton while he was strung out on the road. But the senior general, Charles Lee, wanted to probe the rearguard.

Lee was a curious character. He had been a lieutenant at Braddock’s defeat, so he and Washington were acquainted via service in that campaign. He had been a British lieutenant-colonel and had served as a soldier of fortune in Poland and Russia. Unable to obtain advancement, he contacted an old friend from the Braddock expedition, Horatio Gates, and decided to emigrate. He bought an estate in what is now the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. In June 1775, be became the second man commissioned as a major general, then the senior most rank, in the Continental Army. George Washington was the first.

In the early going, Lee had become something of a negativist. He was convinced that American soldiers couldn’t stand against Redcoats and he seems to have become convinced that the war could not be won. He was dissatisfied with Washington as a commander and wrote numerous letters denigrating Washington and puffing up himself. One of these fell into British hands on 13 December 1776 when Lee was rousted out of his sleep in a New Jersey tavern by a patrol of the 16th Light Dragoons led by Cornet Banastre Tarleton. He was treated as an honored colleague by his former comrades. In early 1777 he put himself forward as a peace commissioner and when those negotiations proved fruitless he gave the commander of the British forces, General William Howe, advice on how to defeat Washington. He was exchanged in April 1778 and returned to duty as an American general. But a lot of water had passed under the bridge since his capture. New commanders had been promoted, like Henry Knox and Anthony Wayne. And there was the whole Trenton-Princeton-Valley Forge thing.

The battle began confused as the Americans, operating without any tactical reconnaissance. While that may have been bad enough, Lee made things worse. He piecemealed regiments into battle and failed to give coherent orders to his subordinates.

True to their training the American army stood its ground and fought it out, toe to toe, with the British. Some of the units took heavy losses. Colonel William Grayson’s 4th Virginia Brigade nearly ceased to exist. A year earlier and the American troops would have scattered in the face of these losses. The battle teeter on razor’s edge.

Since Lee had failed to inform all his subordinates of his plan, an already confusing engagement degenerated into outright chaos. When he finally saw the British 3rd, 4th and 5th brigades advancing over Briar Hill, Lee ordered Maxwell and Scott to line their troops up to face them. When Oswald’s artillerymen were sent back to replenish their ammunition, however, other Continental troops, including Scott’s and Maxwell’s, mistook their retirement for an ordered retreat. Scott also thought that Lafayette was retreating and began withdrawing his own men to the western side of the East Ravine. That left Grayson isolated, and he, too, decided to withdraw to protect himself. Like an avalanche started by a few loose stones, the entire American line began to disintegrate as Lafayette, having been informed that Scott had retired, began to fall back.

Clinton now saw his chance. Ordering Knyphausen to halt, he brought up reinforcements. With 3,000 troops heading toward the courthouse, Cornwallis was ordered to attack immediately with the soldiers at hand and turn the Yankee retreat into a rout.

The Redcoats swarmed over abandoned Yankee positions by Briar Hill. Learning of that, Lee abandoned his feckless attempt at encirclement, and by 1:30 p.m. he had ordered a retreat. At first, he thought about rallying his men in the streets of Monmouth Court House itself, until he discovered that the houses were built of wood — not stone as originally supposed — and could easily be set aflame by enemy fire. He then consulted with his French engineer, Louis Duportail. Duportail pointed out a slight ridge about a mile or so from Monmouth Court House, near the present Catholic cemetery. Perhaps a stand could be made there. Again, though, Lee seems to have been unable to get the word of the plan to his subordinates. So the retreat continued, despite the fact that Lee still had more than 3,000 men, and only 1,500 to 2,500 of the king’s men had actually arrived on the scene.

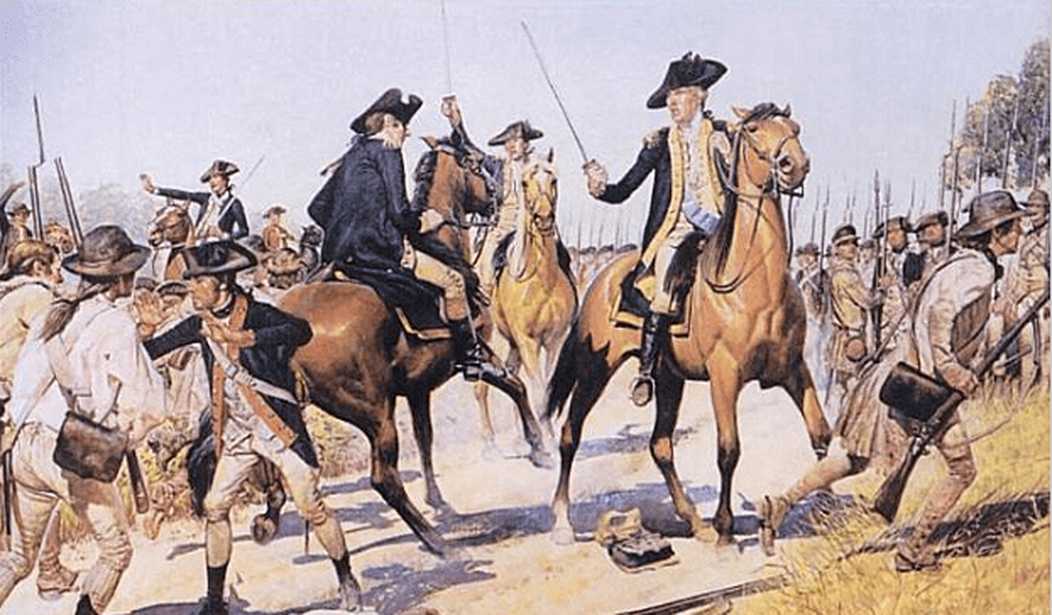

Washington had heard the gunfire and was riding towards it when he encountered a boy fifer who told of disaster. Shortly thereafter he encountered companies and regiments retreating. But they weren’t beaten. They were angry that they had been ordered to retreat. Washington pushed them into a defensive line and sent messengers to recall all units in his army to the battlefield. Then Charles Lee arrived. Washington was an exemplar of gentlemanly behavior. He prohibited his troops from swearing. But desperate times call for desperate measures:

“You damned poltroon,” Washington rejoined, “you never tried them!” Always reluctant to resort to profanities, the chaste Washington cursed at Lee “till the leaves shook on the tree,” recalled General [Charles] Scott. “Charming! Delightful! Never have I enjoyed such swearing before or since.” Lafayette said it was the only time he ever heard Washington swear. “I confess I was disconcerted, astonished, and confounded by the words and the manner in which His Excellency accosted me,” Lee recalled.

In today’s vernacular, Washington told Lee to “pack his sh** and get off the battlefield.” The he started turning chaos into order.

He constituted a reserve under Wayne, a force that could either cover his retreat or exploit a victory. He moved Knox’s artillery onto Comb’s Hill, at the bottom of the map, and enfilated the British lines. But what turned the tide was Washington’s leadership. He literally rode one horse to death. At times he was a bare ten yards from British infantry. By nightfall, both sides were exhausted but the Americans were still on the battlefield. In the middle of the night the British abandoned their camp and marched away.

Lee was angry over his dismissal from command. He damanded a court martial to clear his name but what he got was one year suspension from rank. He never commanded American troops again.

It was an Monmouth that Americans learned they could hold their own with the cream of the British Army. The lesson of Monmouth was well learned. Nathaniel Greene’s Southern campaign showed at Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse that American regulars could use cold steel as well as the British. Monmouth marks the creation of the American Army as a fighting force worthy of the name.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member