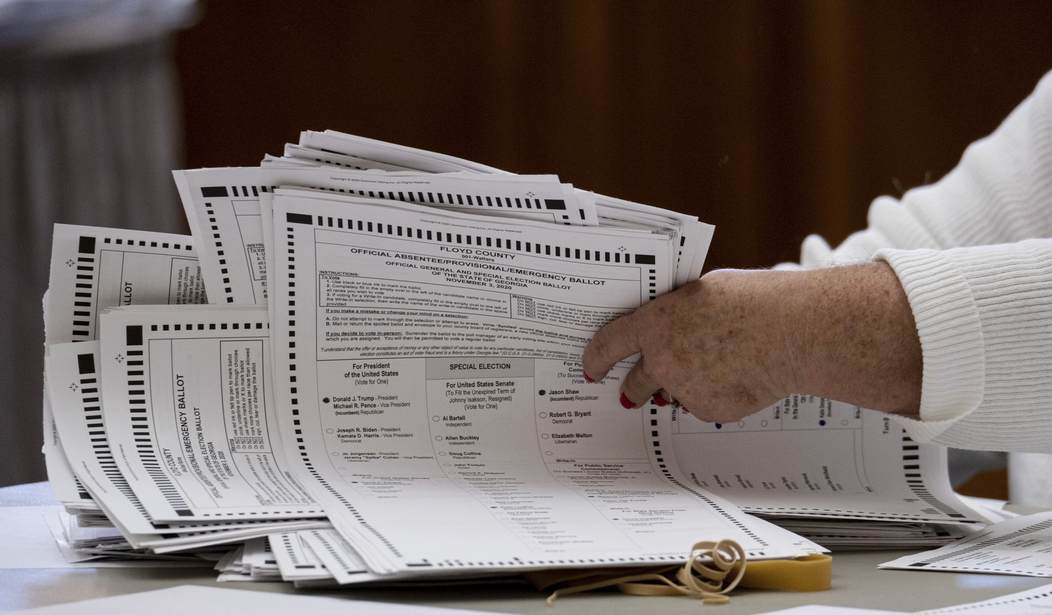

Late in the day on Saturday the Pennsylvania Supreme Court dismissed with prejudice the complaint filed by GOP Congressman Mike Kelly, failed GOP candidate Sean Parnell, and others, claiming that the “no excuse” mail-in ballot option created by the Pennsylvania legislature in 2019 violated Section 14 of Pennsylvania Constitution. That Section limits “absentee” voting to four narrow categories of “absent electors”. The complaint alleged that because Section 14 is itself a constitutional limit on exceptions to in-person voting, the no-excuse mail-in voting statute worked as a de facto amendment to the Pennsylvania Constitution without going through the required process for amending the Constitution.

Without addressing the merits of the complaint in any fashion, the Court ordered the case dismissed on the equitable grounds of “laches”, finding that the “facial” challenge to the constitutionality of Act 77, the law which created no-excuse mail-in balloting, was a matter the plaintiffs could have brought the time the Act was passed. The Court found a lack of diligence from the fact that they did nothing for more than a year, during which time both a primary and general election took place in which “no-excuse” mail-in voting procedures were employed.

I’m going to make a point here, at the outset, that is somewhat out of place because I want the readers to keep it in mind as they read through the remainder of this article.

The Kelly complaint alleges that Act 77 changed the voting process in Pennsylvania in a manner that amended the Pennsylvania Constitution, without going through the process for making amendments to the Constitution as set forth therein.

The opponents of the Kelly complaint — joined by the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in dismissing the complaint — are possessed by the issue of whether millions of Pennsylvania electors will be “disenfranchised if “no-excuse” absentee voting is declared to be invalid due to the complaint.

What I have not seen commented on — and that failure is why I put this issue here at the top — is that one of the approvals required in the process for amending the Pennsylvania Constitution is that proposed Amendments must receive a majority vote of Pennsylvania electors in a general election.

The voters of Pennsylvania were entitled to have a say in whether the Constitution’s provisions regarding elections and voting should be amended. The General Assembly, Governor, Secretary of the Commonwealth, and County Boards of Election DISENFRANCHISED Pennsylania voters by imposing a “no-excuse” change to the “absentee ballot” provisions of the Constitution without first getting their approval.

Keep that in mind when we get to the issue of “prejudice” as part of the application of the “laches” defense below.

Laches is an “equitable defense” to a meritorious and timely legal claim, where allowing the plaintiff to enforce their claim would be unfair due to prejudice or disadvantage that has resulted from the passage of time, coupled with the “fact” that the plaintiff “sat on their rights.” The United States Supreme Court has described the defense thusly:

The defense of laches “requires proof of (1) lack of diligence by the party against whom the defense is asserted, and (2) prejudice to the party asserting the defense.” “`Doctrine of laches,’ is based upon maxim that equity aids the vigilant and not those who slumber on their rights. It is defined as neglect to assert a right or claim which, taken together with lapse of time and other circumstances causing prejudice to the adverse party, operates as bar in court of equity”).

So, in fact, there are actually three elements to the doctrine, the first two of which are often conflated — first, neglect on the part of the plaintiff in not asserting the right; second, a lapse of time; and third, circumstances showing prejudice to the adverse party.

The partisan members of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court were never going to allow the Kelly complaint to be resolved on its merits. All seven members of that court must stand for re-election in partisan contests. Any Judge who had voted in favor of the Kelly complaint would certainly be the subject of open partisan warfare by the Democrat Party of Pennsylvania the next time that Judge runs for re-election.

But, the perfunctory nature of the Court’s treatment of the laches issue might bring it some grief in the days ahead. The Court did not treat the issue carefully, nor did it render a decision with acute legal clarity that is necessary when setting aside a meritorious and timely claim based on an equitable defense.

The Court acknowledges that it rendered its decision only on the filings of the parties in the court below. It allowed no evidence to be taken — which is all the lower court intended to do — even though prior decisions of the Supreme Court describe the application of “laches” as a “fact-intensive” inquiry. Its explanation as to why “laches” should bar the claims raised by Kelly is legally inadequate and fails to account for its own decisions reaching the opposition outcome in earlier election cases.

In short, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court protected the partisan outcome of the electoral tally that it favors — nothing more.

A thorough legal analysis of the historical origins and application of “laches” as a common law equitable defense would be the length of an involved law review article. I am not attempting that here. There is case law on just about every side of the application of “laches” so there is plenty of available language from compelling cases that would contradict what follows.

But I begin my criticism of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court with its own words — from two days ago, and from 22 years ago.

In ordering the dismissal of the Kelly Complaint the Court stated:

Upon consideration of the parties’ filings in Commonwealth Court, we hereby dismiss the petition for review with prejudice based upon Petitioners’ failure to file their facial constitutional challenge in a timely manner. Petitioners’ challenge violates the doctrine of laches given their complete failure to act with due diligence in commencing their facial constitutional challenge, which was ascertainable upon Act 77’s enactment. It is well-established that “[l]aches is an equitable doctrine that bars relief when a complaining party is guilty of want of due diligence in failing to promptly institute an action to the prejudice of another.” Stilp v. Hafer, 718 A.2d 290, 292 (Pa. 1998).

Let’s stop here. I always enjoy reading the cases cited in support of key legal points made by a party, and Stilp is the first key citation to authority made by the Court in its decision. So, what else did the Court say in Stilp?

Stilp involved a constitutional challenge to a statute passed as part of a multi-state compact on dealing with storage of low-level radioactive waste material. That statute was passed eight years prior to the complaint filed by the Plaintiffs. The challenge to the statute was not based on its substance, but rather on the procedures followed in passing the statute. This became a significant basis for the Court finding that the doctrine of laches — after 8 years of delay — applied as an equitable defense to the Plaintiff’s claim.

Also significant in Stilp was the fact that the application of laches came as part of a motion for summary judgment filed 13 months after the complaint had been filed, and after the parties had conducted extensive discovery, i.e., a “fact-intensive” inquiry on the question.

The parties in Stilp — and the Supreme Court in its decision — distinguished constitutional challenges to the substance of a statute from constitutional challenges to the procedural manner in which a statute was passed. Note the following:

Appellants argue that the Commonwealth Court erred in granting summary judgment based upon laches because the doctrine may not be used to defeat a constitutional challenge to a statute. While Appellees concede that laches may not bar a constitutional challenge to the substance of a statute, they maintain that laches may bar a challenge like the one in this case, which only attacks the process by which the statute at issue was enacted eight years ago.

Consider for a moment the “Appellees” in that case — Tom Ridge, Governor of Pennsylania, and the State of Pennsylvania.

“Appellees concede that laches may not bar a constitutional challenge to the substance of a statute.“

Well, the Governor and State of Pennsylvania just argued to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court in the Kelly case, and the Supreme Court agreed, that laches should bar a constitutional challenge to the substance of a statute. That is the exact opposite of what the Governor and State “conceded” 22 years ago. So much for legal and political ethics.

The Court in Stilp also referred to its earlier decision in Sprague v. Casey, also decided in 1988, which the Plaintiffs in Stilp cited for the language “laches and prejudice can never be permitted to amend the Constitution.” But the Court noted in Stilp that the cases cited in Sprague for the proposition that “laches and prejudice” could never be allowed to amend the constitution were cases involving a challenge to the substance of the statutes under attack — not the procedure by which the statutes were passed which was the basis for the challenge in Stilp.

This reference in Stilp to Sprague and those two prior cases further reinforced the distinction between the application of laches to constitutional attacks on the substance of a statute, and constitutional attacks on process. Laches could work to bar the latter, but never the former.

Until Act 77, Joe Biden, and Donald Trump.

But let’s consider further the holding in Sprague because that was an election case. The Plaintiff in Sprague was challenging the decision to place two races for two open judicial positions on the general election ballot in November 1988, which the Plaintiff claimed was in violation of Pennsylvania law. The Plaintiff failed to file his complaint for more than six months after the two races were added to the ballots. A difference in Sprague, however, is that the challenge was filed prior to the election taking place.

Nevertheless, there is key language in Sprague that addresses the issue of lack of diligence and prejudice when it comes to the application of laches to an election contest.

Begin with the fact that the Pennsylvania Supreme Court found that laches did not apply in Sprague even though the Plaintiff did know for many months prior to filing his complaint that the two judgeships were on the ballot, and he did not file his complaint until the eve of the election. But the Court denied the defense of laches to the State Defendants, and their reason for doing so is highly pertinent to the complaint filed by Kelly:

Respondents contend that the petitioner unreasonably failed to commence this action for six and one-half months from the time he had actual or constructive notice of his claim…. In the instant case, petitioner had not only to discover the facts surrounding his claim, but also to ascertain the legal consequences of those facts. It is asserted petitioner, as an attorney, is deemed to be familiar with the mandate of the Constitution of this Commonwealth, and thus should have been immediately aware of his claim. The candidates-respondents, however, are also lawyers and are candidates for offices on the two highest courts in this jurisdiction, and should be charged with the knowledge of the Constitution as well. Respondents are requesting that this Court use its equitable powers to deny petitioner relief; yet, they have made no effort to seek judicial approval of the scheduled election. He who seeks equity must do equity. Mazer v. Sargent Electric Co., 407 Pa. 169, 180 A.2d 63 (1962), Hartman v. Cohn, 350 Pa. 41, 38 A.2d 22 (1944). To find that petitioner was not duly diligent in pursuing his claim would require this Court to ignore the fact that respondents failed to ascertain the same facts and legal consequences and failed to diligently pursue any possible action. We cannot say that respondents who seek to invoke this equitable defense have acted equitably in this manner. In light of the foregoing, we cannot say that petitioner failed to pursue this matter diligently.

Whaaa??? What???

Did the Pennsylvania Supreme Court say in Sprague that whether legislative action is lawful is a question known to both the plaintiff who challenges the action, and the State Officials who took the action, such that each had a concomitant obligation to diligently seek out an answer regarding that legality? Did the Court find that State Officials cannot complain about the failure of the Plaintiff to act diligently in that regard if the State Officials had not taken any action on the same matter to validate the legality of their actions?

Yes — that’s exactly what the Pennsylvania Supreme Court said in Sprague. The state officials knew that putting the judgeships on the general election ballot was potentially a violation of state law, and they did not seek judicial sanction for their decision as they could have done. Since they had not been diligent in seeking to defend their action, they could not — in equity — complain about the Plaintiff’s lack of diligence in seeking to challenge their action. “He who seeks equity must do equity.”

The same is true with regard to Act 77. The Legislature and Governor knew Act 77’s introduction of “no-excuse” mail-in balloting was an expansion of the “absentee voting” limits established by Sec. 14 of the Pennsylvania Constitution. Their knowledge is reflected in the fact that they simultaneously advanced separate legislation intended to be a proposed amendment to Sec. 14. They faulted Kelly and the other Plaintiffs for not seeking to make their factual challenge to the constitutionality of Act 77 immediately upon its passage, but they failed to seek a judicial sanction of their immediate implementation of Act 77’s adoption of “no-excuse” mail-in balloting.

That is the precise basis upon which the same Court in Sprague determined that it could not find a lack of diligence on the part of the Plaintiff in that case. .

In dismissing the Kelly complaint, the Supreme Court doesn’t even mention the fact — even though it refers to its earlier decision in Sprague.

But there is a second aspect to the “imprecision” of the Pennsylvania Supreme Court’s decision, which is based on the briefing of the issue to the Court by the State Defendants, and that is the issue of “prejudice.”

As I noted by italisizing part of the language of the United States Supreme Court on “prejudice” that I quoted near the top — the reference is to prejudice to “the respondent” — the defendant in the case.

But the Pennsylvania Supreme Court followed the lead of the briefing by the State — it relies on “prejudice” to voters who would be “disenfranchised” by the remedy sought by the Kelly complaint. It did so without even pausing to consider whether this is appropriate “prejudice” that the Court should take into account in determining whether the defense of laches should apply.

“Laches” is an affirmative defense. Voters aren’t parties to the Kelly complaint and do not assert “defenses” to the claims made. Voters aren’t “prejudiced” by the fact that the case is pursued. There is no outcome yet in the case. There is no “disenfranchisement” unless Kelly prevails on the merits and invalidating all mail-in ballots is the only remedy to be imposed.

Under Pennsylvania law, an invalidly cast ballot is void that shall not be counted in the tally of votes. A ballot is either validly cast according to law or it is invalidly cast — the cause is irrelevant.

There are invalidly cast ballots in every election, and those ballots are set aside. Those voters are disenfranchised. So voter “disenfranchisement” is not an uncommon occurrence in elections.

The fact that there may be 2.3 million such invalid ballots is not the fault of the Plaintiffs bringing the Kelly complaint. By refusing to allow the case to be resolved on its merits, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court is likely violating Pennsylvania law by allowing invalid votes to be included in the final tally.

And this takes me back to the point I made near the top. The voters of Pennsylvania are given a meaningful and necessary role in amending their State’s constitution. A vote of a majority of the electors in a general election is the required final step to adoption of such amendments. The Defendants in the Kelly complaint deprived the Electors of their right to validate the proposed amendment passed by the General Assembly, and they put the amendment in place without their approval.

That was “disenfranchisement” of the Pennsylvania electorate. Who is to say that Pennsylvania voters might have rejected “no excuse” mail-in balloting if not for being disenfranchised.

Let us not kid ourselves about what the real “prejudice” is the Supreme Court was worried about with regard to the Kelly complaint. The real prejudice that concerned the Court was that Joe Biden might not get the benefit of the illicit acts of partisan democrats in control of the state’s elections.

Addendum: There are questions in the Comments about whether the US Supreme Court might take up this case. This is a final judgment of the highest court of the State of Pennsylvania, so it is a decision which is reviewable by the US Supreme Court. But, as a general proposition, the Court only reviews decisions from state courts that implicate federal law. If the decision is viewed purely as a matter of state law, the US Supreme Court generally defers to the highest Court in the State to resolve such issues.

But “laches” is not “state law” — it is an equitable defense to a claim. The “claim” made here involves the process for Amending the Pennsylvania Constitution with regard to the “manner” by which Electors to the Electoral College are chosen. The Pennsylvania Legislature — and Pennsylvania voters — have placed certain aspects of the “manner” for selecting electors in the Pennsylvania Constitution. The Legislature and the State Actors are alleged to have changed those aspects of the “manner” for selecting electors in a way not allowed by the Constitution. That is a question the US Supreme Court could take up if it so chooses.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member