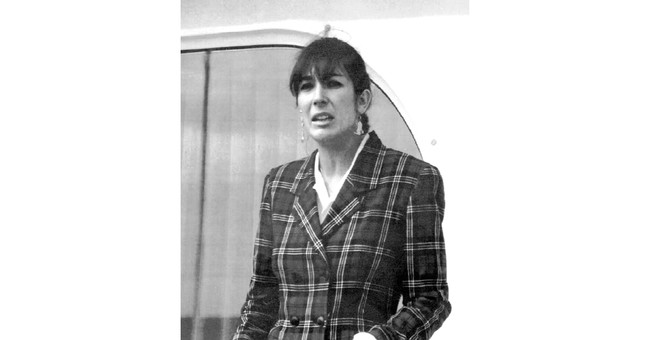

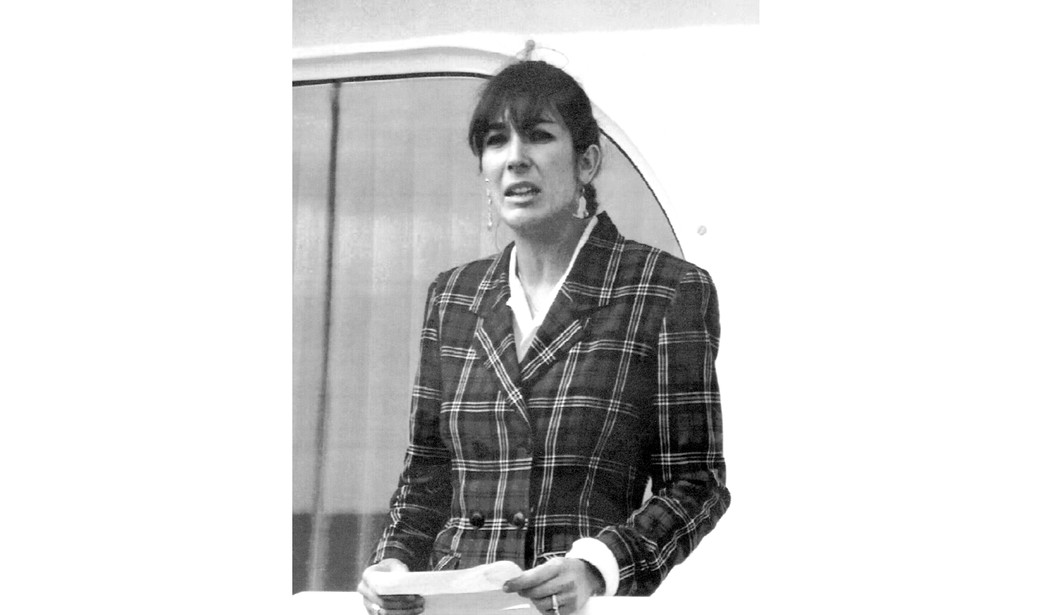

A federal indictment was unsealed today in New York charging Ghislaine Maxwell, one-time girlfriend and longtime confidante of accused sex trafficker Jeffrey Epstein, with six counts of criminal activity in connection with her participation in Epstein’s sexual activity with underage girls. Epstein died in his jail cell shortly after his arrest in 2019. The official cause of death was listed as “suicide”, but the matter remains under investigation, and the absence of evidence that would normally be available as part of such an investigation — like video recordings of he movements around Epstein’s cell around the time of his death — have been determined to be unavailable.

There are several noteworthy features in the 18 page indictment returned against Maxwell.

First, she is charged in Count One with “Conspiracy to Entice Minors To Travel To Engage in Sex Acts.” The time frame of the conspiracy as set forth in the indictment is 1994 to 1997, although the language used in the indictment is such that evidence of conduct on either side of those two dates — but relatively close in time to the referenced years — would likely be admissible in a trial.

But it is beyond “rare” to have a federal prosecution mounted based on allegations of conduct dating back to a time frame 23-26 years prior to the indictment. The most logical explanation for this is that under the particular facts of this case, the prosecutors determined that the most credible victims upon whom they could base charges were women now in their late 30’s or early 40’s who will be able to take the stand and testify about what happened to them while having a personal background and history that will survive the assault on their credibility and truthfulness that will form the foundation of any defense to the charges. The indictment specifically refers to three victims who were abused by Maxwell and Epstein in the time frame covered by the indictment — Victims 1, 2, and 3.

In making the necessary statutory allegations to set forth a crime of conspiracy, the indictment refers to Maxwell, Epstein and “others known and unknown” as conspirators. Much might be made of this reference, but that doesn’t mean there is much significance to such language. This is standard language that appears in any federal indictment charging conspiracy. It does not suggest that other individuals will be charged — or even identified. The benefit of having such language is that it leaves open the possibility under the Rules of Evidence that the government can introduce evidence regarding the conduct of other individuals not named as having been part of the conspiracy. “Co-conspirator” evidence is a particular kind of evidence that can sometimes be introduced in criminal cases, and that is most easily made possible by the allegation of a conspiracy in the indictment, and a reference that there might have been one or more people involved in the conspiracy than those defendants named in the indictment.

The Epstein case has had many prominent individuals mentioned over the years as possibly having a connection to his illegal conduct. The indictment names only Maxwell and Epstein and is specific to a relevant time frame. Any individual who is said to have a connection to Epstein — where that connection is for conduct not between 1994 and 1997 — is not someone who might fall within the reference to “persons known and unknown.” Its possible that the selection of the time frame is purposeful for that reason, as some who who have been connected in press reports cannot be fit into that specific time frame.

Count Three of the indictment charges the existence of a separate and second conspiracy — Conspiracy to Transport Minors With the Intent to Engage in Criminal Sexual Activity.

Normally a conspiracy charge would include all the “criminal objects” of a conspiracy in a single count. It is unusual to see two separate conspiracy charges in the same indictment if it was possible that one conspiracy charge could have incorporated multiple criminal objectives. One possible explanation for having two separate conspiracy charges here is that different individuals might be engaged in both, and the “overlap” of common individuals is not significant enough to allow all the illegal conduct to be “lumped in” to just one conspiracy. Alleging and proving two different conspiracies may be simpler from an evidentiary standpoint. The evidence of one might be stronger than the evidence as to the other, so alleging them separately gives the jury the opportunity to convict on one or both.

But a second reason to charge two conspiracies here is that there is a greater maximum penalty attached to a conspiracy charge tied directly to the “Transportation” offense — up to 10 years in prison. The only conspiracy charge available for the “Enticement” offense is the “general” federal conspiracy statute under 18 USC Sec. 371 — which carries a maximum sentence of only 5 years.

In other words, the “general” conspiracy statute (Sec. 371) applies to a conspiracy to violate any federal law, and is punishable by no more than 5 years. But the “Sex Transportation” statute has a subparagraph that makes it a specific crime to “conspire” to violate the “Transportation” statute, and that “conspiracy” is punishable by up to 10 years in prison. There are a few federal statutes in which Congress determined that they should have their own “conspiracy” subparagraph, but this is very much the exception, not the rule.

BUT — and here is a signal that should not be ignored — the indictment does not charge Maxwell with the 10 year conspiracy statute under the “Transportation” statute — it charges her with a conspiracy under Sec. 371. That means that even though they could have exposed her to a 10 year sentence by using the offense-specific conspiracy charge, they chose to only expose her to a five year sentence under the general conspiracy charge. That is not an accident.

She is charged with a single count of under the “Enticement” statute, and a single count under the “Transportation” statute. She is also charged with two counts of perjury that are linked to false answers she gave under oath in a deposition as part of a civil case pending in the Southern District of New York in which she was named as a defendant.

The significance of the fact that she was charged with only the five year conspiracy statute, and not the ten year conspiracy statute, suggests to me that there is already a guilty plea and cooperation agreement being discussed. She can plead guilty to both conspiracy counts, and maybe one of the perjury counts, and face no more than 60 months in custody. She might be able to work that number down with cooperation in the investigation or prosecution of others.

Sometimes those kinds of deals are accomplished in advance — but sometimes the actual indictment becomes the final application of “leverage” by the prosecutor that ends up delivering the deal that has been offered and rejected. If she refuses, the prosecutor can return to the grand jury and seek the 10 year conspiracy count that the “Transportation” statute provides, thereby creating significantly greater risk for her with regard to the possible sentence length following conviction.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member