Note: the following review contains major plot spoilers.

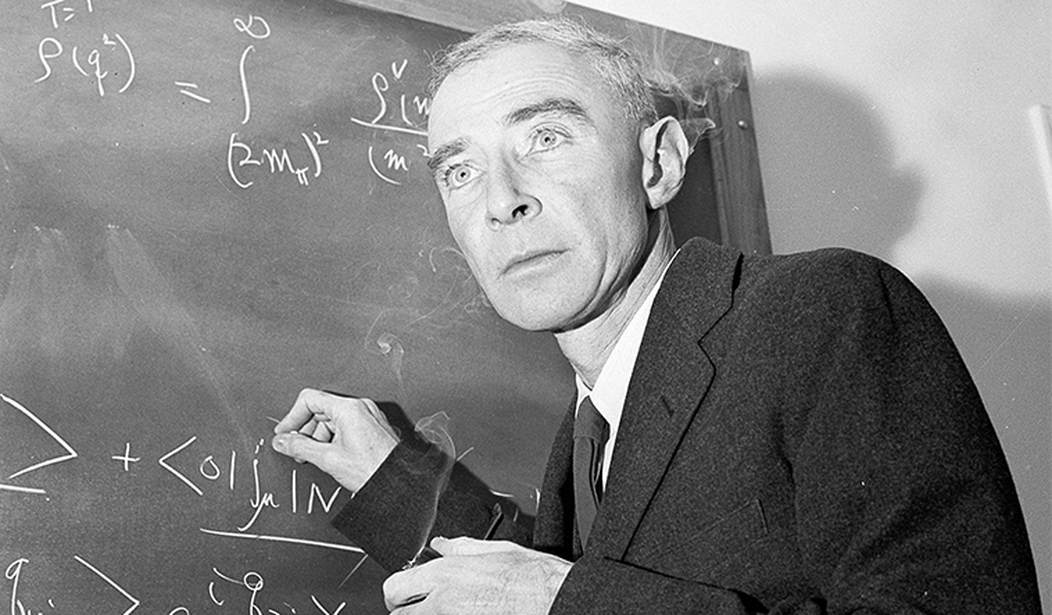

“Oppenheimer” is a 3-hour epic about the life of J Robert Oppenheimer. In certain ways, it’s reminiscent of how movies used to be made. The dialogue is smart. The editing was crisp, and (because I know the sound editor), the soundtrack was terrific—being “big” when it was needed and subtle when required. It’s also a “whodunit” wrapped in soft commie propaganda inside leftist messaging.

For most of its three-hour run, Oppenheimer straddles multiple fences about big-picture principles and personal morals. For instance, none of the scientists working on the Manhattan Project had moral qualms about nuking Germans citizens yet, almost universally, they revolted against the prospect of vaporizing Japanese citizens. So much so that they circulated a petition to stop its Fat Man and Little Boy as a weapon against Japan.

The film juxtaposes Oppenheimer’s genius against his almost childlike naivete and nearly nonexistent personal morals. It begins with young Oppenheimer poisoning his instructor’s apple with cyanide. Why? Because his professor told him to finish his work. The next day, Oppenheimer returned to prevent his intended murder. Later in the film, when asked about his murder-by-poison plot, that he must have “hated” the professor, he said: “Oh no, I very much liked him.” Oppenheimer’s motive to murder a man was presented as a youthful indiscretion.

The film bends time by blending Oppenheimer’s 1954 security clearance revocation hearing with the 1957 Senate Commerce Committee hearing on the nomination of former AEC chairman Lewis Strauss. Christopher Nolan flips back and forth from Oppenheimer’s security clearance hearing (shot in color) to the Commerce Committee public hearing, as if they are being held contemporaneously. All of the committee scenes are shot in black and white, with the clear intent to cast the Strauss hearing as a comeuppance moment in the vein of the McCarthy v Joe Welch’s Army hearing, in which Welch said: “You have done enough. Have you no sense of decency? But in the movie, a Senator isn’t the bad guy—it is Lewis Strauss, the witness and nominee.

The movie soft-pedals Oppenheimer’s lack of personal morals throughout. Besides Oppenheimer’s youthful murder plot, he and his wife Kitty couldn’t stand the sounds of their infant crying. What was the solution? They took their baby to the home of Haakon Chevalier and his wife Barbara, both of whom were communists. “Oppy” and Kitty weren’t dropping the baby off for a one-night break; Oppy and his wife were getting rid of their child. Oppenheimer asks Chevalier if he is a “bad person”. Oppenheimer is assured that just asking the question means he isn’t a bad person thus absolving Oppenheimer of the moral guilt he clearly never had.

While married, Oppenheimer met up with former lover and always communist Jean Tatlock for sex. He only demonstrated angst about it after she committed suicide. Was he bothered by her death or what it would do to his reputation? Kitty clearly cared more about how the affair would affect her lifestyle than how it was adulterous and immoral.

The movie also soft-pedals Oppenheimer’s decade-long interaction and his admitted dalliance with communism as just “intellectual curiosity” about Marxism. The movie (and by extension, the man) never explains how a genius who read “Das Kapital” in the original German didn’t recognize communism as a blight. Oppenheimer recognized Nazis as imperialists and evil, as Jew-hating madmen but apparently couldn’t see the Jew-hating Karl Marx and mass-murdering Joe Stalin in the same light. The film follows a well-worn script that communists weren’t “all that bad”. It tracks the oft-used illustration of how communists were “ruined” just for being communists. It never mentions that most American communists were counting on and willing to foment a Soviet-style revolution in America.

At the tail end of the movie General Leslie Groves, the man who oversaw the Manhattan Project, admits during Oppenheimer’s security clearance hearing that Oppenheimer would not be granted a security clearance based on the 1954 guidelines. The film suggests that Groves’ objectively correct admission was a bad thing, and the Manhattan Project would have failed without Oppenheimer running it. There is little evidence to support that suggestion. The project would have gone forward with or without Oppenheimer having clearance.

“Oppenheimer”s final act demonizes Lewis Strauss and lionizes Oppenheimer. Strauss is cast as the antagonist, because why not? Strauss and Oppenheimer didn’t agree on how to deal with the Soviets’ nuclear buildup. In my opinion, Strauss saw the Soviets in a clearer light: as an oppressive and murderous lot intent on world subjugation and world domination. Was Strauss also manipulative? A political animal in a pack of other political animals? Sure. Welcome to reality. But “Oppy” engaged in an impossible effort to put the nuclear genie back in the bottle, and for that, he is presented as the film’s hero. Not for building the bomb and helping end a bloody world war, but for tilting at windmills. The film wants you to engage in silly wish-casting, that had America engaged with the USSR early in arms talks, as Oppenheimer suggested, the production of hydrogen bombs may not have happened. That, of course, is Pollyanna-ish nonsense.

The film informs the audience the Strauss Senate confirmation vote came down to three, unanticipated “no” votes. According to the film narrative, the deciding vote came from a young John Kennedy. Strauss is befuddled. He asks an aide: “Who is this John Kennedy?” pretending that Strauss wouldn’t know who the son of Joe Kennedy was. The film doesn’t bother with the uninteresting fact that Strauss’ nomination was torpedoed, not because Strauss wasn’t qualified for the job (he was) or because Strauss was conflicted over Oppenheimer’s opinions; the nomination was scuttled largely because of the personal animus of a dozen Senate Democrats. It was personal—nothing more. Kennedy didn’t cast his no vote because he was upset over Strauss’ opinions about Oppenheimer. Kennedy voted “no” for base reasons. Political reasons. Kennedy got something in return. But Hollywood will always mythologize Kennedy because he was the prince awaiting his crown,the future king of a fictional Camelot—and Hollywood never passes up a chance to mythologize Jack Kennedy.

“Oppenheimer” is an interesting story, but the film is way too long. It spends too much time mythologizing a conflicted (mostly immoral) man and ultimately left me empty – not caring for the man beyond the fact that (if he liked it or not) helped end the war against Japan with the deaths of 100,000 dead civilians. Oppenheimer had an unintended hand in my dad coming home from the war. For only that reason, I thank him.

Not mentioned in the film, but of note: the current Energy Secretary, Jennifer Granholm reinstated the security clearance of the long-since-dead Robert Oppenheimer as vindication against mean Joe McCarthy and the bad, very bad anti-communist Republicans. Much like the film, that act was empty moralizing wrapped in leftist virtue signaling inside of political puffery.

In short, there are better ways to consume three hours of your time.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member