Los Angeles County Director of Public Health Dr. Barbara Ferrer made news Tuesday when she told the county’s board of Supervisors that the “Safer at Home” order would almost certainly be extended for three more months when it expired May 15. Outrage ensued, and the Board of Supervisors and Ferrer herself walked back those comments. Turns out that walk-back was just a giant “psych!” because Ferrer announced the new order Wednesday – one with no expiration date. But, give her credit for being literal – it wasn’t a three-month extension.

To say that the vast majority of county residents are upset is an understatement. As we at RedState have argued throughout our collective quarantine, the people making these decisions are people with stable, steady paychecks – paid for by We the People. Ferrer definitely fits in that category, but the amount of her salary is stunning. According to Transparent California, a watchdog group, Ferrer’s total compensation package in 2018 was $553,249.

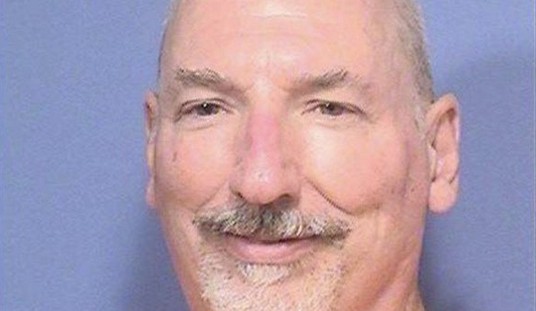

Screenshot

Los Angeles is an expensive place to live, but wow.

Here at RedState we have also pointed out that our public health “experts,” particularly Dr. Anthony Fauci, are not infallible deities, and that doctors aren’t qualified to run the entire country.

In “Doctor” Ferrer’s case, she’s not an epidemiologist or virology expert. She’s not even a medical doctor, as KABC’s John Phillips discussed on his radio show Wednesday. Her educational resume, from a bio published at USC, where she was a panelist at a “Safe Schools” symposium:

Dr. Ferrer received her Ph.D. in Social Welfare from Brandeis University, a Master of Arts in Public Health from Boston University, a Master of Arts in Education from the University of Massachusetts, Boston, and a Bachelor of Arts in Community Studies from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

What in the world is a Bachelor of Arts in Community Studies, besides a waste of money? Apparently it is the first step on a career path to becoming a “nationally-known public health leader,” as USC says (emphasis added):

Dr. Barbara Ferrer is a nationally‐known public health leader with over 30 years of professional experience as a philanthropic strategist, public health director, educational leader, researcher, and community advocate. She has a proven track record of working collaboratively to improve population outcomes through efforts that build health and education equity.

Her most recent position before joining the LA County Department of Public Health was with the W.K. Kellogg Foundation:

“[W]here she was responsible for developing the strategic direction for critical program‐related work and providing leadership to the foundation’s key program areas: Education & Learning; Family Economic Security; Food, Health & Well‐Being; Racial Equity; Community Engagement; and Leadership Development.”

There may be a place in society for people with Ferrer’s training and expertise, but does her experience qualify her for this position during a pandemic? The Los Angeles Times writes:

In Ferrer’s role as the top health officer in a county of 10 million people, she’s in the middle of every tough conversation about which businesses and institutions have to shut down, whether public and private hospitals are equipped and prepared to handle a possible surge, and what each of us has to do to make a difference.

She’s our very own local version of White House infectious disease expert Anthony Fauci, the straight-talking, overworked doctor now so visible that I feel as though I can tell how many hours of sleep he gets each night.

They also noted Ferrer’s Social Justice Warrior bona fides:

Ferrer was born in Puerto Rico and spent her childhood there. Then, as a young activist, she became a community organizer focused on unequal healthcare access for the poor. She thought about becoming a doctor, but after earning a bachelor’s degree at UC Santa Cruz, she attended Massachusetts universities for master’s degrees in education and public health, followed by a doctorate in social welfare.

In other words, she chose a life of “poverty” to remain an activist.

Other counties in the state, such as San Diego and Alameda, have actual MD’s for county health officers, but Ferrer’s allies say that Ferrer relies on MD’s on her staff for necessary input.

Nevertheless, despite Ferrer’s “leadership,” Los Angeles County has an extremely disproportionate number of Wuhan flu infections and deaths. With just over 10 million residents the county is home to approximately a quarter of all Californians, yet essentially half of both of the state’s confirmed coronavirus cases and deaths are in the county.

How much of that is due to Ferrer’s policy focus and lack of will to take aggressive measures to clean up the county? Ferrer came to the county in 2017 and quickly focused on homelessness issues, understandably. Downtown Los Angeles was getting grimier and deadlier by the day, and the blight had started spreading throughout the county. Ferrer inherited a massive problem, no doubt, but over two and a half years or so has shown a stunning lack of initiative in the face of major public health concerns.

When there was an outbreak of typhus in Los Angeles in 2018 and 2019, infecting 20 people, including one Los Angeles Police Department officer, Ferrer didn’t declare an outbreak and had to be ordered by the Board of Supervisors in June 2019 to develop a plan to minimize the risk of additional cases:

“In the interest of protecting the health and safety of our residents and law enforcement personnel, the county must examine the root causes of the spread of communicable diseases associated with trash and rodent infestations, and develop a comprehensive plan to minimize risk of additional cases,” [Supervisor Kathryn] Barger said.

The disease is typically caused by contaminated food or water and is different from typhus, which can spread to people from infected fleas and their feces.

An employee at City Hall East came down with typhus last year, which led to a exhaustive inspection of city buildings in the Civic Center area. Department of Public Health Director Barbara Ferrer said a multi-pronged approach to disease prevention was required.

Well, no s**t.

“I don’t think there’s a simple answer,” [Ferrer] said.

Yes, there are some simple answers – as part of a multi-pronged approach. The buildings have rat infestations because the streets are filled with trash, human feces, and the petri dishes otherwise known as the tents of people experiencing homelessness. The streets are filled with mentally ill people who won’t shower or otherwise participate in normal, healthy hygiene practices because they are mentally ill and not receiving proper treatment or medication.

But, when your Department of Public Health Director is an activist with a Ph.D. in Social Welfare from Brandeis, the Berkeley of the northeast, you cannot expect true solutions with a scientific basis. In October 2019, when the Board of Supervisors directed Ferrer’s department “to examine and execute strategies that lead to a rapid reduction” in the number of homeless people dying on the streets (which had doubled between 2013 and 2018), here’s Ferrer’s game plan:

“As we work hard to secure housing for those experiencing homelessness, we have a civic and moral obligation to prevent unnecessary suffering and death. We need to start this work by speaking directly with those experiencing homelessness to better understand how to align our support.”

So, you’re going to talk to unmedicated paranoid schizophrenics to better understand how to align your support of them? You’re going to talk to drug addicts and alcoholics who are only thinking about how to keep the buzz going about policy? No. When people are unable to care for their basic needs, you get them help. Immediately.

Despite the typhus outbreak of 2018-19 and a massive increase both in the numbers of homeless people living and dying on the streets of Los Angeles County, Ferrer counted the department’s blessings in her year-end newsletter:

“We have been blessed this year with outstanding leadership from the Board of Supervisors, our workforce, county department partners, our unions, community leaders, and residents. Collectively, we formed powerful alliances that brought about policy and practice changes in communities, workplaces and schools.”

Oh, great, you had “outstanding leadership” from your unions and “formed powerful alliances.” The 1,100-plus homeless people who died on your streets are sure grateful for that.

Here are the “accomplishments” she lists:

- We worked with many of you to promote a “care first, jail last” model for our most vulnerable residents who are often refugees from failed social and economic systems.

- Together, we established the LA County Office of Violence Prevention where community organizations and county departments can implement efforts that eliminate violence in our neighborhoods schools, workplaces, homes and relationships.

- This month, we opened 34 of our 50 Wellbeing Centers at high schools across the county so that students can build their leadership skills, make good choices, and have opportunities to receive support from their peers and caring adults.

- Many of you helped us respond to outbreaks, and with your assistance, we were able to contain and prevent further transmission of communicable diseases such as mumps, measles, and flea-borne typhus.

- Community environmental justice leaders led efforts where we partnered to prevent and mitigate the devastating consequences of exposures to known chemical hazards.

A “care first, jail last” model “for our most vulnerable residents who are often refugees from failed social and economic systems”? Coming in dead last in her newsletter were the people sleeping on the streets – some of whom probably could have been helped by Skid Row drug dealers being put behind bars:

And we all worked hard to address the crisis facing 59,000 people experiencing homelessness by expanding services, realigning resources, and intensifying efforts to prevent people from dying on our streets.

No solutions, but they worked hard on a lot of nebulous things. Gold star.

During each weekday’s press conference, Ferrer notes how many new coronavirus deaths have occurred over the past 24 hours and expresses her sincere condolences to their families. As one of the county supervisors noted in the LA Times bio, Ferrer’s genuine concern is visible. In a world that is often unkind and views human beings as numbers or statistics, Ferrer’s individual focus is welcome and good. But until Ferrer also concerns herself with the millions of human beings who are experiencing severe mental distress because they’re locked at home in bad relationships or abusive situations, who are unable to obtain necessary (but not emergency) medical/dental care, whose businesses and life’s work are being decimated, and allows them to return to regular life, her words are hollow.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member