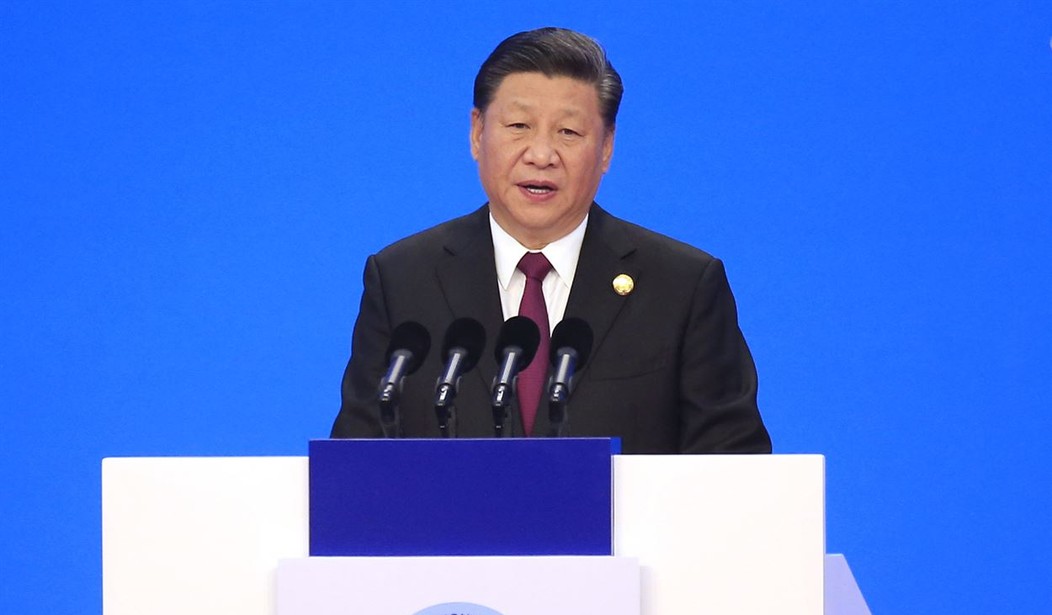

Chinese President Xi Jinping speaks at the opening ceremony for the China International Import Expo in Shanghai, Monday, Nov. 5, 2018. Xi promised Monday to open China wider to imports at the start of a high-profile trade fair meant to rebrand the country as a global customer but offered no response to U.S. and European complaints about technology policy and curbs on foreign business. (Aly Song/Pool Photo via AP)

At the end of March, The Guardian published an article entitled, “China sees a new wave of xenophobia.” The lede reads, “Fears rise that Beijing is stoking mistrust of foreigners as part of an attempt to rebuild a reputation tarnished by the coronavirus crisis.”

At the time, China had begun to report “imported cases” of coronavirus. For the week ended March 28, for example, Chinese health officials “reported only six locally transmitted cases but dozens arriving from abroad. By last Thursday [March 26], officials had reported a total of 595 imported cases since the outbreak began, the main source being the UK.” According to the Chinese foreign ministry, “90% of the imported cases were Chinese passport holders.” So the new anti-foreign sentiment seems misplaced.

These reports have begun to turn the Chinese people against foreigners living in their country. And foreigners are feeling the chill.

According to the article, “experiences have ranged from socially awkward to xenophobic. An American walking with a group of foreigners in a park in Beijing saw a woman grab her child and run the other way. Others have described being called foreign trash. Last Saturday, the country temporarily closed its borders to all foreign arrivals. Officials have also ordered local airlines to maintain only one route per country per week.”

Andrew Hoban, a 33-year-old man from Ireland who now lives in Shanghai, told The Guardian, “I’m walking past someone, then they see my blue eyes and jump a foot back.”

An American historian who lives in Beijing said, “There is an effect when state media are reporting this is a foreign virus. It is a new variation of a familiar theme: don’t trust foreigners. If there is another flare-up in China, the blame will fall on people coming from outside.”

Mike Gow, a lecturer at Coventry University’s School of Strategy and Leadership believes this is “the leadership’s attempt to shore up its image. If there is an opportunity to make themselves look strong, competent and legitimate by capitalising on public anxiety, they’ll take it. If that happens to stoke xenophobia, so be it.”

Here are several other experiences recounted to The Guardian:

But some foreign communities are experiencing more harassment. An African couple in Beijing were made to wait for two hours at a restaurant before a worker let slip that they were not supposed to allow in heiren – “black people”.

“The combination of pre-existing attitudes to race and Africans, plus this new wave of fear of foreigners, is making things worse,” said Runako Celina, co-founder of Black Livity China, which documents experiences of Africans and people of African descent in China. “Despite us doing this work steadily throughout the years, I don’t think there’s been a single period of time when we’ve had as many racism [or] discrimination-related incidents from different people and provinces.”

Others describe more scrutiny and wariness. American David Alexander, 32, who lives in the southern province of Jiangsu, said his Chinese co-workers had been advised to stay away from foreigners. In a shop last week, a couple waited until he had left before entering. “There is a sense of fear around foreigners,” he said.

A British-Canadian software engineer living in Shenzhen described being stopped several times by police and asked for her papers, something that did not happen before.

The issue is being replicated across Asia. In Vietnam, hostility toward foreigners has reached such a level that the Vietnamese ministry of foreign affairs issued a statement calling for it to stop.

“It is our hope that the spirit of humanitarianism, equality and non-discrimination will be upheld by the entire international community, so that citizens from all countries and territories can enjoy security, safety and healthcare,” the statement said.

In Thailand, a since-deleted Twitter account operated by the country’s health minister reportedly said the country had to be “more careful of westerners than Asians” because they “never shower” or wear masks. He later denied writing the tweets. In Taiwan, some restaurants have reportedly said they will not serve foreign diners.

In the last couple of days, several new articles indicate that anti-foreigner sentiment among the Chinese has deepened further in just the past three weeks.

Hot Air’s John Sexton writes about an incident that took place in a Chinese McDonald’s. Before being kicked out of the country along with several other American journalists, a NY Times reporter described his experience:

Having a quick meal at a half-filled McDonald’s before heading for the train station, my colleague and I were quietly talking when a young man wearing a bright yellow hoodie approached. He pointed at me. “You foreign trash,” he said. “Foreign trash! What are you doing in my country? And you, with him, you bitch.”

He hovered over us menacingly for a few minutes before moving on. His tirade, and the fact that no one in the restaurant said a word, felt bleakly appropriate.

An article in Friday’s New York Times entitled, “As Coronavirus Fades in China, Nationalism and Xenophobia Flare,” actually appears to give an accurate assessment of the change in the attitudes of many Chinese. It begins by telling readers, “Now that the pandemic is raging outside China’s borders, foreigners are being shunned, barred from public spaces and even evicted.”

In Beijing and Shanghai, foreigners have been barred from some shops and gyms, supposedly as part of a campaign to combat the virus. “We are temporarily not accepting foreign friends and people whose temperature is above 37.3,” read a sign in a hair salon near Beijing’s central business district.

A salon employee said she didn’t see it as discrimination. “It is an epidemic, after all,” she said…

Some expressions of antiforeigner sentiment have made no pretense about public health concerns. Last month, a porridge restaurant in the northeastern city of Shenyang displayed a banner that read: “Celebrating the epidemic in the United States and wishing coronavirus a nice trip to Japan.”

What would account for this new distrust of foreigners? The writers of The NY Times piece, who are both Chinese, believe it was caused by the daily reports of imported cases of the virus in the state-run media.

Some of the uglier manifestations of nationalism have been fueled by government propaganda, which has touted China’s response to the virus as evidence of the ruling Communist Party’s superiority…

China’s heightened us-against-them mentality is perhaps most apparent in its recent strictures aimed at foreigners. Though the Chinese government denounced racist attacks against Asians overseas when the outbreak was centered in China, it now casts people from other countries as public health risks.

In other words, the CCP is doing what they always do — they are shaping public opinion. At this point, the Chinese government is well aware of how far they’ve fallen in the eyes of the world and they’re trying to control the story within their own country.

I was surprised to see articles that were critical of the Chinese state media and government in the Guardian and the New York Times. Is it possible that the truth about China is finally sinking in?