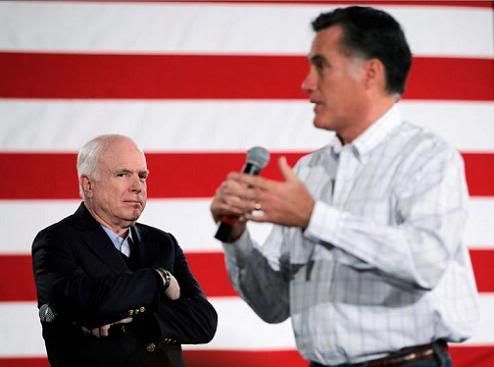

It can be difficult to summarize in one place all of Mitt Romney’s problems as a candidate and as a potential President. I have tried; I wrote, back in 2007, a series so lengthy on Romney’s flaws (some 15,000 words, Part I, II, III, IV & V) that I can’t possibly hope to rewrite the whole thing now, and explained why I preferred McCain to Romney. More recently I focused on the dangers of backing Romney to the integrity of his supporters, the conservative movement’s need to maintain its independence from Romney, and the problems with Romney’s technocratic approach. Let me try to zero in on four of his problems here: the unconvincing nature of his political conversion, the hazards of becoming enamored with candidates whose primary rationale for running is their money, the unprecedented difficulty of winning with a moderate Republican who lacks significant national security credentials as a war hero or other prominent foreign policy figure, and Romney’s vulnerability arising from his dependence on his biography.

I. The Unconvincing Convert

One argument that’s been made in favor of Romney (including by a number of people I respect who are trying to find a way to support him in good faith) is that both the Republican Party and the conservative movement should, and do, welcome converts – and thus, Romney’s history of being on the wrong side of practically every domestic policy issue should not be an obstacle to accepting him into the fold now.

Now, it’s important that we recognize the full scope of what we are dealing with here, because Romney supporters often try to draw false equivalences to other Republicans who have changed positions on issues over the years. You need to examine Romney’s history in this regard in its full detail to appreciate that his record of flip-flops and deviations from conservative and Republican positions is on an order of magnitude beyond anything else out there.

You can start with this DNC oppo video, which despite including a few ticky-tack attacks and ignoring a number of his major flip-flops does a devastatingly effective job of showing how easy it is to dramatize Romney’s dizzying changes of position over the years, and sometimes over as little as a single day:

I went in detail through Romney’s flip-flops and their meaning back in Part III of my 2007 series: abortion, immigration (more here), guns, the Bush tax cuts, campaign finance reform, Don’t Ask Don’t Tell, No Child Left Behind (see here, here and here on that last). This is before we even address his position on health care, although as I noted last time, Romney claimed in 1994 to be opposed to the use of mandates in health care. And even this list doesn’t fully capture the entirety of Romney’s enormous record in such a short career of taking positions opposed to the current conservative view, as every new controversy reveals another – witness Romney’s record (after his supposed conversion to the pro-life cause) on compelling Catholic hospitals to dispense ’emergency’ contraception.

As I discussed in 2007, Romney’s flip-flops are uniquely damaging to him because (1) there are so many of them, (2) they came relatively recently in his public career, and in most cases he has spent little or no time in office developing a record of fidelity to the new positions, (3) he didn’t really offer plausible explanations for them compared to his oft-impassioned explanations for holding the earlier positions and (4) there really isn’t one central core to Romney as a political leader that is free of flip-flops, no one thing we could be sure he’d never compromise on. Thus my characterization of Romney’s record as a sheet of thin ice as far as the eye can see.

All of that helps explain why Romney is broadly mistrusted, why nobody can really be sure if he’ll stick with his newly-minted positions when the going gets tough. But I need to expand here on the third point.

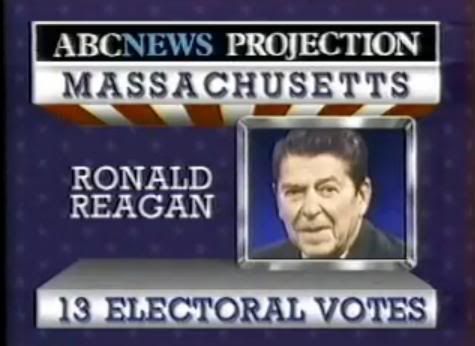

The Republican Party is chock full of converts. People get more conservative as they get older, get jobs and families, experience more of life. Even many of our most prominent leaders were once liberals or Democrats or both, Ronald Reagan foremost among them (two of the candidates I’ve supported against Romney – Rudy Giuliani and Rick Perry – were former Democrats). Movements and groups in the party (from neoconservatives to Dixiecrats to Reagan Democrats) have often been identified on the basis of their prior affiliations on the other side. Change in party affiliation, policy positions or political philosophy, alone, is not reason for excluding people from leadership roles.

But here’s the thing: politics, even presidential politics, is only partly about exercising power; it is just as much about persuading people of ideas and their implementation in laws and programs. A political leader is, for better and worse, the salesman of his or her party’s ideas and proposals. Converts can actually be tremendous ambassadors for winning over new people to their party’s standard, because they understand how to speak to the doubts people on the other side may have about their own positions. And they can talk the audience through the process of their conversion, explaining how they came to realize they were wrong, or detailing how the other side changed (in Reagan’s famous phrase, “I didn’t leave the Democratic Party, the Democratic Party left me.”)

Romney never does this. He admits, grudgingly, his flip-flop on abortion, because it’s the most prominent one, but even there, his explanation of how he became a pro-lifer over the stem cell issue (oddly, an issue on which many pro-life Mormons are not on the pro-life side) is less personal and less convincing than his prior narrative of how a family experience led him to be pro-choice. The dual conversion narrative leaves both positions sounding hollow and insincere: St. Paul only went to Damascus the one time.

And after that, it gets worse. If Romney really believed that his past positions on tax cuts, guns, immigration or campaign finance reform were terribly misguided, he could pepper his stump speeches with the kind of stories Reagan so often told about how he came to see that the old Democratic ideas just didn’t work in the real world. He doesn’t, and perhaps as the son of a Republican governor, presidential candidate and Cabinet secretary, he knows it would ring hollow. If anything, Romney bristles and throws back other people’s changes in position when his are raised (a tendency Drew M. has compared to internet trolling). He’s so busy trying to sell conservatives on the notion that he’s bought our ideas that he doesn’t have it in him to sell those ideas to anyone else. Jonah Goldberg and others have talked about how, as a convert, Romney often seems to have the words but not the music of conservatism, to not know the language. But that’s precisely what a convert to a new set of ideas usually possesses in excess: an enthusiastic desire to share with the world what it was that made him change teams. The fact that Romney can’t do this in convincing fashion and barely tries is not just a clear indication that his changes of position are matters of political convenience, but also why he has no chance of selling the voters on conservative and Republican policies if he can’t really explain why he was won over by them himself. This is a serious liability in a general election, and a serious liability for a president as well. Even if Romney’s primary opponents prove too flawed to stop him, it should worry us greatly about the future of our party’s ability to convince anyone that we stand for anything worth believing in.

II. The Money Man

A second problem I have with Romney, and which worries me greatly if he wins, is that he is precisely the kind of candidate that political consultants, campaign professionals and the campaign committees in the GOP love, and who lead us over and over again to defeat.

(Side note: if Romney’s the nominee, I will fight for him to win, because the stakes are too high to roll over and accept an Obama re-election. But that doesn’t mean I need to be blind to the costs of Romney winning).

Political consultants love candidates who enter races with a lot of money and not much in the way of a political record or political convictions. Such candidates can be tailored to a script and platform developed by the consultants, they spend money on the consultants and their businesses, and when the candidate inevitably fails because he or she lacks the natural political instincts and convictions to speak well off script, the consultant can just shrug, say there’s only so much you can do with a bad candidate, and move on to the next one. Over and over, Republicans have lost races with such people, and if Romney manages to back his way into a victory this fall, we shall never be rid of them.

We all know, whether or not we admit it, that Romney (who has heavily outspent his rivals in negative advertising in his key victories in Florida and Michigan) would not be the frontrunner in this race if he didn’t have the most money. Patrick Ruffini gave a great, detailed account a few years back of the many flaws of wealthy candidates:

The dollar signs dancing around in consultants’ heads don’t make up for the fact that most self-funders tend to be subpar candidates for important structural reasons. First, they’re political dilettantes unfamiliar with the rigors of elected politics. They make rookie mistakes. They assume their records before their recent entries into politics aren’t relevant or won’t be scrutinized. They have less political acumen or knowledge than many of the people I follow on Twitter, or even most of them.

And that’s just when they start running. Once they do, they run overkill levels of TV, and often resort to slashing negative ads to dislodge better known competitors, which drives their own negatives up….The gaudiness of the campaign operation tends to infect media coverage late in the game, and that’s when self-funders really get worked over by the traditional press corps, which tends to counter-balance the perceived buying of the election with uniquely skeptical coverage when voters are actually paying attention. And as any student of campaigns will tell you, earned media is far, far more valuable than paid media, even at inflated levels of spending.

From an ideological perspective, self-funders are political chameleons. Since they’re somewhat politically attuned, they’re likely to have been a donor, but like most big donors, they’re pragmatists who’ve played both sides. And it’s not uncommon for these rich candidates to have made donations to fashionable lefty social crusades. The country-clubbers who have supported Focus on the Family or the National Rifle Association with their philanthrophic dollars are few and far between.

All of this should sound familiar (from Romney’s political tin ear to his carpet-bombing ad campaigns to his donations to Planned Parenthood). And as Ruffini pointed out, it gets worse when you consider the downstream effects of how a campaign built around money rather than principles warps the entire structure of the party and the movement:

And there’s another element here that shouldn’t be tolerated: corruption. To put it indelicately, when a mega-self-funder gets in, people get bought. Local parties are capitalized to the tune of tens or hundreds of thousands of dollars with endorsements magically appearing shortly thereafter. People who couldn’t afford to take salaries before can now take salaries. Others get put on the campaign payroll. Elected officials who’ve fought hard and risen through the ranks suddenly become fans of political “outsiders”, leaving their own integrity and intellectual honesty open to question.

In any system where money rules, conservatives lose. When endorsements and political support are rooted in money, not principle, that’s just as great an insult as choosing a moderate over a conservative in a red state on electability grounds. This is not a matter of being a campaign finance zealot as it of avoiding bad and unreliable candidates who tend to lose at alarming rates.

There are certainly strong reasons to suspect that Romney has at least tried to do just this, in the way he has spread his money around over the years to people who turned up as his allies later (see here, here and here, here), most notoriously by donating money to help retire Tim Pawlenty’s campaign debts as Pawlenty has stumped for Romney. This is how you get Romney surrogates attacking people for things they themselves voted for.

Money is not a bad thing, and its presence in politics is inevitable. But the sooner we prioritize being a good candidate over being a well-funded one, the better for our prospects as a party.

III. The Naked Moderate

Here’s another overlooked point: Romney is trying to run as a novelty, a Republican who has neither the strong loyalty of any domestic faction nor a corresponding strength on national security.

It is true that Republicans have nominated moderate, Establishment-backed candidates before. But if you look at the moderate Republicans to win the nomination since Eisenhower defeated Robert Taft in 1952, you will notice they all have something in common: all of them had military service records (several being war heroes of one sort or another), and all had significant foreign policy credentials. And several of them ran to the right of their primary opponents on national security, trumping domestic policy divisions. Ike, of course, had been Supreme Allied Commander in World War II, and faced an opponent (Taft) who was seen as somewhat isolationist; Ike was elected during the Korean War. Nixon, a WWII veteran who was more or less a moderate on domestic policy in 1960 and 1968 and a liberal by 1972, had made his name as an anti-Communist and been a two-term Vice President; he was elected at the height of the Vietnam War. Ford, a WWII Navy combat veteran, was nominated while already the sitting President. George HW Bush, a WWII Navy aviator who was shot down over the Pacific, was sitting 2-term Vice President (like Nixon, a VP whose duties were mainly in the foreign policy realm), and had been Ambassador to the UN, US representative in China and CIA Director. Bob Dole, crippled from his WWII injuries, had been in the Senate for decades and two-time Senate Majority Leader. John McCain, of course, spent a quarter century in the Navy, suffered torture as a POW in Vietnam, was first elected to Congress as an anti-Communist, focused throughout his Senate career on foreign policy and ran in 2008, during the ‘surge’ phase of the Iraq War, as an Iraq hawk and champion of the surge. Every one of these candidates, successful or not in November, led with their foreign policy/national security credentials and experiences.

(George W. Bush was moderate on a fairly large number of major issues, but even in 2000, Bush’s strength on taxes and social issues made him the more conservative candidate in the race and a favorite of many in the electoral base; Bush ended up as the third-most-conservative president of the past 100 years, after Reagan and Coolidge. So I don’t really class him as a moderate).

Romney has none of this going for him. He’s never served in the military, and his main, modest foreign policy experience is from running the Winter Olympics in Utah. These are not absolutely disqualifying factors for a presidential candidate; George W. Bush had little to no foreign policy experience as Texas Governor (really, just dealing with Mexico); Bill Clinton had none at all. But they mean that Romney will be going into battle without one of the key credentials that other moderate Republicans used to command respect and keep their party united. He’ll have the weakest base of core support of any GOP nominee since Dewey or possibly Willkie.

IV. Policy Talks, Biography Walks

Look: a great country takes all types, and Mitt Romney is one of the kinds of private citizen who contribute enormously to making America great. He’s smart, articulate and fantastically disciplined and hard-working. He was a fabulously successful businessman, intimately involved in the development of many new and growing businesses during his career in venture capital and private equity. He ran the Salt Lake City Olympics well, rescuing it from a corruption scandal as well as the challenge of handling the extra security that came from hosting the Games just five months after September 11. He’s obviously a good family man, a man of faith and unquestioned personal integrity. He seems like the kind of guy anyone would be glad to have as a next-door neighbor or a son-in-law. He’s the kind of shirt-off-his-back guy who would ride out in the dark on a JetSki to save a drowning family and their dog, or shut down his entire business for days to help a co-worker rescue his kidnapped daughter, or give 15% of his income to charity. If we lived in a world without ideological conflict and were simply choosing a manager from among our most upstanding citizens to be a political leader, Mitt Romney would be near the top of anyone’s list.

But that’s not the world we live in, and we need to choose a candidate who can handle the world as it actually is. Ideas matter. As I’ve explained before, you persuade voters to your side by making arguments about philosophy and public policy and then tying them back to their real-world consequences. Romney’s insistence on campaigning on his biography rather than his principles is one of the reasons I compared him in 2007 to failed Democratic campaigns of the past, and he’s had the same problem this time – he hasn’t articulated a concise message on economic policy so much as he’s just told people that Obama is a failure on jobs and he’s a businessman here to help. And that, in turn, only makes him more vulnerable to the frequent gaffes that stoke dislike of Romney’s life of wealth and privilege.

All of this is why Romney cannot win in November; the best he can hope for is to stand by and let Obama lose the race. I believed in 2008 that Romney was unelectable; I still believe that was true of that race (although in retrospect it’s hard to imagine any Republican winning after the mid-September financial crisis). I can’t say that with the same certainty this time around; as Sean Trende and others have explained in great detail, Barack Obama is an enormously vulnerable incumbent president, one with an LBJ-sized credibility gap in his constant predictions that the economy is seeing the light at the end of the tunnel (remember “Recovery Summer”?). The electorate doesn’t believe in his policies and doesn’t believe in his results. If high oil prices dovetail with a double-dip recession, Obama could simply collapse, no matter who his opponent is. But I still believe Romney is a terrible general election candidate, who will need a lot of good fortune and outside help to end up winning, and that just about anybody will be able to beat Obama in those circumstances.

Maybe Romney wraps up the primaries tomorrow, and he’ll go a long way towards doing that if he wins Ohio. He’s had chances to follow up wins before and blew them, but the voters sooner or later may throw in the towel and let him finish things off. But nobody who wishes the Party of Reagan well should regard that prospect with anything but grim resignation. This is no way to run for president.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member