“Bigot.” “Opportunist.” “An eye for the sensational.” “He has mercury in his blood.” These are not the words from contemporaries and opponents from his era, but they are used by historians to describe the man who birthed American journalism. That is not to say Benjamin Harris did not inspire similar invective while alive; one of his critics then stated he was simply “the worst man in the world.” Rather fitting that this is the character who kicked off what has led to the quagmire of our contemporary media complex.

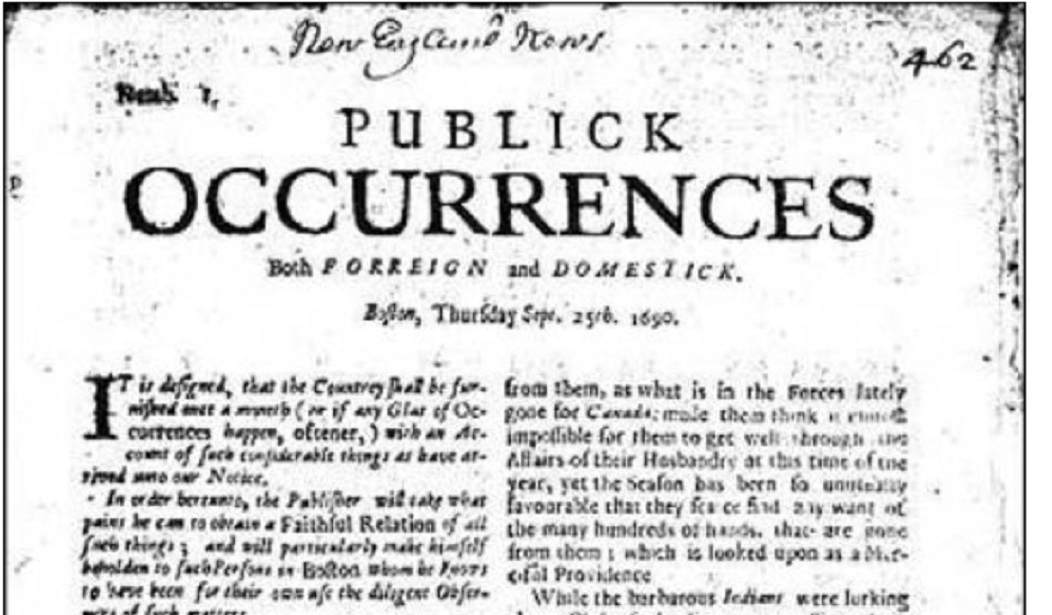

It was three hundred and thirty-three years ago on this date that the citizens of Boston were blessed with a unique and historical item to whose significance they were quite likely oblivious. Comprised of four pages, each measuring 7.6 x 11.5 inches of folded papyrus, they were, on that Thursday, reading what was actually the first newspaper in the United States.

Their copy of Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick might have struck them as a curiosity — in both content and in format — but likely they were not gobsmacked at this new arrival. Some of those who came across the Atlantic might have been exposed to newspapers in London or those offered up for resale locally. Also, many a colonial was putting out printed items to be offered for public consumption, yet the edition that emerged on this date in 1690 was, in truth, unique.

Citizens were used to seeing either pamphlets handed out, notices displayed publicly in playbill fashion, or broadsides which were either distributed and/or posted. These were all single-sheet editions that citizens would have local printers dash off so they could get a message out to the local gentry. You could consider these to be similar to what we see on social media timelines today, where a person feels the public will become edified by these personally distributed notices. (Okay, they are more than just similar to the rambling Facebook posts we encounter today.)

But Benjamin Harris had a little more in mind in reaching out to the burgeoning metropolis — population roughly in the thousands — that was Boston in his day. Harris had rented a wooden edifice (calling it a “shack” would both be accurate and a disservice to the historical significance) for printer Richard Pierce, where Harris would become editor and publisher of Publick Occurrences. So much of this inauspicious debut of American journalism is fitting for today’s media industry, beginning with the fact that Harris was a sonofab**** of a character.

The publishing career of Harris began in Britain, where he put out a number of anti-Catholic publications, as well as being a participant in the Popish Plot. (This was a fraudulent conspiracy cooked up by opponents of the Catholic Church in England that there was allegedly a plan by church leaders to kill King Charles II, which ultimately led to almost two dozen people being executed and nearly as many perishing in prison.) He also wrote in opposition to King James VII's ascending to the throne, resulting in his being arrested on sedition charges.

By 1689, following his release, he fled Britain for the New World and opened up a coffee house in Boston that featured books and foreign publications for sale. He also served as a book publisher, putting out volumes and an almanac. By 1690, though, he hit upon the idea of his own newspaper. More than a simple broadside, Harris wanted to deliver a comprehensive coverage of varied items. What he concocted broke the format of a single message sheet, instead opting for a two-column display of a collection of topics, which would comprise multiple pages. His concept was planned to be a monthly issue with some ambition attached, as he allowed for additional editions to arrive, saying, “If any glut of occurrences happen, oftener.”

Harris intended to forge the way for future papers in the colonies and even displayed techniques we see frequently this day. His paper, as entitled, would cover global and local affairs. Foreign items would be culled from the papers printed in Britain he sold in his shop. Local details came in the form of gossip he collected by ear from locals and overheard in the taverns. In this way, Harris was the first practitioner of aggregated news gathering.

To say this was a crude news delivery system is a fair read. He was not against sensational topics, and these were lumped together in a format, as he gave no news breaks to segregate his entries. Matters involving the British crown might be followed immediately in the next paragraph with an entry on a breakout of smallpox. His coverage of international issues involving Canada might close with the very next sentence concerning a local farmer who hung himself in his barn.

His paper came in four pages, with paragraphs filling the columns on three pages. The fourth page was left blank so readers could fill in their own thoughts on the preceding matters. This way, someone might lend their impressions about an entry, and then it would be read by someone else as the paper was shared and passed on. In a way, this could be considered the very first appearance of a Comments Section.

Harris would also run afoul of the local government. Before fleeing England, one of his last publishing efforts was a pamphlet called English Liberties, in which he called for an expansion of citizen rights and a criticism of the monarchy for not supporting those that currently existed. That anti-authoritarian attitude carried over to the new continent, as he basically refused to get the required license to start his paper business. Adding to the antagonism, the content of his publication contained items that concerned local authorities.

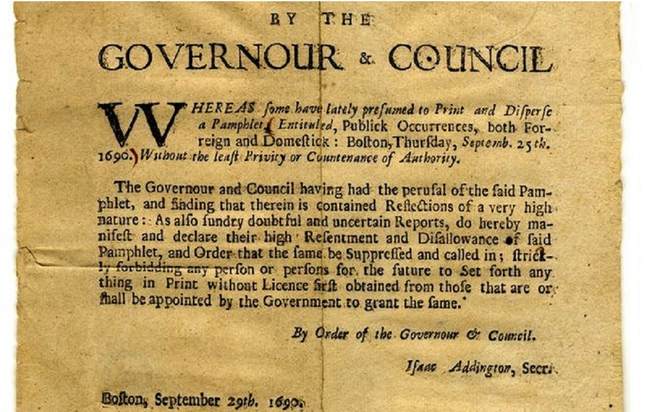

Once his paper circulated, those in power got a glimpse of its contents and they called to take action. Colonial officials put a call out to put an end to things. The Governour issued an order of Resentment and Disallowance and called for Harris to be collected and his paper to be suppressed. His operation was shut down, Harris was arrested, and the remaining copies of Publick Occurrence were destroyed. The lone remaining physical issue of this newspaper was found in a British records repository in 1845

As a result, America’s first newspaper lasted for all of one issue. There would not be a follow-up publication for more than a decade, yet some of Harris’ techniques endured, such as the column format and a willingness to editorialize on the front page. It seems almost fitting that this scoundrel of a man would launch journalism in the country, as the tendency towards the tawdry remains, the questionable sourcing of stories endures, and the brazen disregard for verified facts is entrenched to this day. Media historian John Tebbel summarized it thusly: “It is safe to say no major American institution has been launched by so unworthy a pioneer.”

The legacy of Benjamin Harris appears to exist throughout our media landscape today. With respect to Tebbel, I would suggest Harris is a worthy originator, as so much has been unchanged after more than three centuries.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member