Here’s something that kind of sneaked up on this interminable 2024 presidential campaign:

Nearly two out of three adult Americans think it’s time that voters in this country had another party to consider voting for because the Democrats and Republicans have done such “a poor job.”

You can guess why this is: Overwhelming majorities of adult Americans dislike the leading choices of the two major parties that appear at the moment to be preparing to nominate Joe Biden and Donald Trump — a rerun of 2020, which left a bad taste, bitter feelings, and countless court cases.

Republicans in a handful of unrepresentative but strangely influential states will get to express their preference from a field of seven or so starting, as of now, with January’s Iowa caucuses.

New Hampshire, however, being New Hampshire, has a state law requiring the fifth smallest state to be the first of the 50 to vote in primaries. That probably means a date in early January, followed by the Iowa caucuses on Jan. 15, then South Carolina on Feb. 24.

New Hampshire Democrats didn’t like Biden even before he became POTUS. In the 2020 primary there, the ex-vice president received no delegates. He finished in fifth place, far behind party heavyweights like Amy Klobuchar and Pete Buttigieg, who used to be mayor of the city where Studebaker used to make cars.

So, Biden or his minions arranged for that party's 2024 process to begin with South Carolina on Feb. 3, then Nevada Feb. 6.

He must be worried, having refused any primary debates and facing political powerhouse Marianne Williamson.

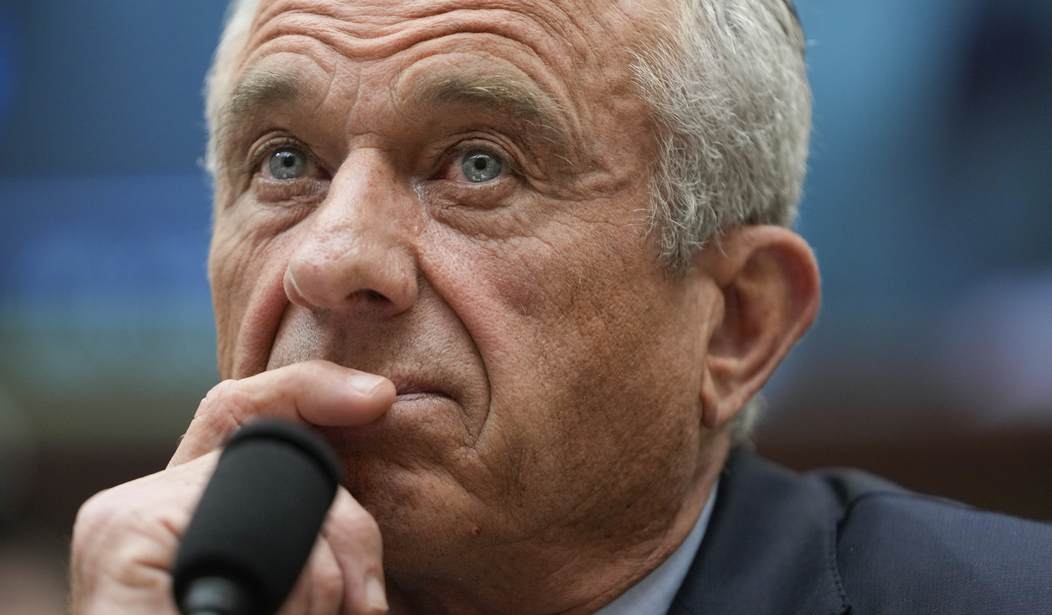

Robert F. Kennedy Jr., realizing the delegate deck was stacked against him, just dropped out of the Democrat contest to launch an independent bid.

And that, along with the new Gallup Poll, got me digging into the possibility of a third-party bid to pull us out of today’s political paralysis (See GOP House speaker fight).

The Founding Fathers disliked political parties, suspecting they would, over time, come to represent their own interests more than constituents'. Imagine that!

We got them anyway.

There were two at first, the Federalist Party and the Democratic-Republican Party. They soon fell apart.

By the 1830s, a familiar format emerged with two dominant parties -- Andrew Jackson’s Democrats, which believed in a strong presidency and activist government, and Henry Clay’s Whig Party. That consisted of business types, social reformers, evangelicals, and Jackson’s conservative opponents, who leaned more toward congressional dominance.

By the mid-1850s, as would happen often in the future, a major issue spawned a third party: slavery. The newly-born Republican Party emerged as anti-slavery, and in 1860, became the first and so far only third party to elect a president, a Midwestern country bumpkin lacking formal schooling named Abraham Lincoln.

He captured just under 40 percent of the popular vote. Northern Democrats, Southern Democrats, and the Constitutional Union Party split the rest, giving him the Electoral College win at that time among 33 states.

Four years later, Lincoln would form the country’s only bipartisan presidential ticket with Tennessee Democrat Andrew Johnson, a former legislator and governor.

They were overwhelmingly successful as a unity ticket, but Lincoln’s assassination and Republicans’ impeachment, though not conviction, of Johnson, sank that concept. Johnson returned home to become the only ex-president ever elected to the Senate.

Countless third parties have come and gone since. Today, believe it or not, we have nearly five dozen political parties, 37 of which have run presidential candidates.

Typically, they form over an emergent major issue, then, like a shooting star, perish after a brief, bright journey across the sky.

The Republican and Democrat Parties have been too clever, broad, big, and adaptive, often co-opting the emergent issue and absorbing its proponents. The words "political chameleon" come to mind.

The good news is that pattern has saved the U.S. from the fragmented, multi-party parliamentary systems like Italy, France, and Israel.

The two parties are also entrenched because of their national organizations and the difficulty others have concentrating votes to break into the Electoral College. It’s winner-take-all by states. So, good showings must be focused on achievable states.

Safe to say, if 18th-century Democrats and Republicans saw their parties today, the cigar ashes would ignite their beards.

In 1912, after sitting out a term, Theodore Roosevelt challenged his Republican successor, Howard Taft, and sought reelection with his new Bull Moose Party.

The result: The two Republicans split the conservative vote, handing the election to progressive Democrat Woodrow Wilson, who introduced the country to the income tax, World War I participation, and the spectacle of lengthy, in-person State of the Union deliveries every single year. Thanks for your service, professor.

A third party again played a major role 70 years later. George H.W. Bush’s successful Gulf War brought him an 89 percent approval rating.

This chased off less-than-courageous A-team Democrat challengers. Even Jesse Jackson declined to run, leaving an undistinguished band of lesser-known wannabes, including Paul Tsongas, Doug Wilder, Tom Harkin, and some governor from Arkansas.

Bush had a serious GOP primary challenger in Pat Buchanan, who made much of Bush reneging on his famous 1988 promise, “Read my lips, no new taxes.” That is usually an ominous sign. Ask Jimmy Carter about Ted Kennedy in 1980.

Enter from stage right a Texas billionaire named Ross Perot. He was 5 feet 5 inches tall, a little man fighting for the little man. Americans prefer tall presidents; half of them have been around six feet or taller.

But the fast-talking, blunt-spoken Perot had been chief executive of several corporations. He financed his own campaign and became a folk hero for straight talk about his impatience and frustrations with the federal government, especially its profligate spending habits.

It's a theme of Heartland anger and frustration with D.C. that a Fifth Avenue billionaire would mine quite effectively 24 years later.

Perot's platform included balancing the budget, economic nationalism, and electronic town halls to bring democracy participation to the homes. Hello, Zoom 30 years later. He also believed drugs were weakening the American spirit and soul.

Perot phoned me once to say he admired one of my newspaper stories. I thought it was a prank, but that raspy Texas voice was too distinctive. I had several fascinating phone conversations with him over the years and learned a lot.

They were off-the-record at the time, but maybe since he passed away a few years ago, I’ll write them up someday.

With the 1992 campaign filled with the usual political blather and doublespeak, Perot’s straight talk struck a national chord. He made the budget deficit a major issue and vowed to balance it, as he had in businesses that he owned, which were not subject to voter approval.

Campaigning for his son in New Hampshire in 1999, an energized President Bush told me candidly one afternoon backstage that he knew he would lose the 1992 election two weeks before Nov. 3.

The 1992 election was a multiple-candidate choice like Lincoln’s in 1860. Bill Clinton fell far short of a popular vote majority (43 percent) to Bush’s 38 percent and Perot’s 19 percent.

Clinton took 370 electoral votes, 100 more than needed, to Bush’s 168.

Perot got none, but he siphoned off enough popular votes in just the wrong places to deny Bush sufficient states. Perot remains the only non-major party candidate since 1968 (George Wallace) to carry individual counties and finish second in some states.

Despite significant differences, Bush’s presidency, in retrospect, felt like a third Reagan term, creating a desire for a fresh start with the unknown Clinton, despite rumors of sexual assaults. Would Hillary's hubs survive under today’s Me Too standards?

Despite his famous family name, Robert Kennedy’s campaign has displayed none of the verve or charisma of his father or Perot. His anti-vaccine stance is quite popular with some but strikes others as too quirky.

Whoever tells Biden what to do these days was wise to prohibit any primary debates. The contrasts with the raspy but well-spoken Kennedy at 69 and the engaging Marianne Williamson at 71 would be devastating if Biden had one of his confusion outbursts or silent staring spells.

Kennedy is charisma-free. He's not electrifying, and neither are his campaign themes: “We will end the forever wars, clean up government, increase wealth for all, and tell Americans the truth.”

But without Perot’s vast financial resources, Kennedy will be forced to rely on earned attention from media, which is also captivated by the two-party attention span. Third-party candidates like the Green Party's Ralph Nader can rarely utter their talking points before being asked why they’re bothering to run.

Perot had the vast resources and media savvy to shatter that, but still couldn’t capture one state.

The unusual twist for the 2024 campaign, however, is Kennedy could affect the election outcome, not by winning, but by siphoning off votes from both major party candidates.

There are the vast number of Democrats who detest Trump but know Biden is incapable of a second term, and also fear Kamala Harris as an inadequate backup.

And there are independents and Never Trumpers in the Republican Party who couldn’t stomach a Biden vote, but see Kennedy support as a benign protest if he manages to get on state ballots.

Wouldn’t it be politically amazing if that bizarre combination created a perfect political storm that unexpectedly thrust into the White House the third-party son and nephew of two anointed Kennedy brothers who so ambitiously sought the job?

Nah, that could never happen.