When Gunpowder Went Smokeless - Germany Makes a Move

Previously on RedState: Sunday Gun Day XXIX - The History of Bolt Guns, Part I

Sunday Gun Day XXX - the History of Bolt Guns, Part II

While the French were developing the Lebel, Europe’s first military smokeless powder repeater in mass production, the Germans weren’t hiding behind the door.

In response to France’s adoption of the Lebel rifle, the Germans did something that rarely happens – they formed a government commission that successfully designed a cutting-edge infantry rifle.

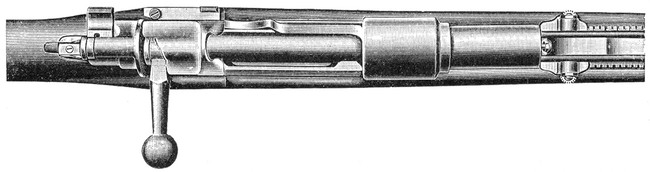

The 1888 Commission rifle had a five-round magazine and a bolt with two locking lugs at the front of the bolt body. While the 1888 is frequently referred to as the 1888 Mauser, this is incorrect, as Mauser had no hand in the design of this weapon and made few, if any, of the almost three million Commission rifles; most were made by the Ludwig Loewe works (later renamed the Deutsch Waffen und Munition-Fabriken, or DWM) by the Steyr works in Austria and by Imperial arsenals at Amberg, Danzig, Erfurt, and Spandau.

The 1888 Commission rifle was only in primary German service for ten years, but it did have one outstanding characteristic: its cartridge. The 1888 Commission rifle introduced the 7.92x57mm (generally known as the 8x57 Mauser) cartridge in its original Patrone 88 J-bore configuration, firing a .318 diameter, 227-grain round-nose slug at about 2400 fps.

The 7.92x57mm cartridge would effectively father an incredible variety of rifle cartridges. Such legends of riflery as the great .30-06 Springfield, the .308 Winchester, and the .270 Winchester share its case head, which has become damn near standard for medium-power bolt gun rounds. Unlike the rimmed Lebel case, the 7.92x57mm was rimless, using an extraction groove in the case to remove fired cases from the chamber; this made it easier to feed rounds from a magazine quickly, smoothly, and efficiently.

Down in Oberndorf, Paul Mauser was, to put it mildly, displeased at the German government’s bypassing his design people to build their own infantry rifle. Mauser-Werke was at the time still churning out the 71/84 rifle, but Paul Mauser had some ideas, and if the German government didn’t want an improved Mauser, there were other governments in Europe and elsewhere that would.

The Run-Up to the Final Mauser

Mauser’s late-nineteenth-century battle rifles went through three main phases, each marked by several technological innovations. Those phases included:

- The 1889 Belgian, 1890 Turkish, and 1891 Argentine Mausers

- The various 1893-1895 small-ring Mausers, which include the 1894 and 1896 Swedish Mausers

- The 1898 Mauser

So, let’s look at each in turn.

By today’s standards, the 1889/90/91 rifles looked a little odd, at least if you’re used to more modern Mauser-type actions. Missing was the big claw extractor. The magazine was a protruding single-stack affair, loading (in the case of the1891) five of the new 7.65x53mm Argentine cartridge, a fast, powerful round for the time. But these rifles did retain the 71/84’s over-the-top safety and the bolt locked securely into the receiver ring by the expedient of two large opposed locking lugs at the front of the bolt.

Some years ago, I picked up an 1891 Argentine that had been re-barreled with a 7x57mm tube and had a Redfield peep mounted on the receiver. I put on a nice blonde walnut stock with a narrow Schnabel fore-end; I re-blued the action and refinished the wood, had the bolt body jeweled, and a butterknife bolt handle installed. It was a beautiful rifle, handy and light; I fed it mild handloads and killed a few deer and a couple of javelina with it.

The Belgian Army used their 1889 model in the Great War; the Ottoman Turks still had some by that fateful day in 1914. All in all, a little over a quarter-million of these rifles were made.

Following close on the heels of the Belgian/Turk/Argentine rifles came a new design, which entered the market with what became known as the 93/95 action. This was a more modern-looking piece, retaining the safety but exchanging the single-stack magazine for a flush-fitting staggered-stack magazine, and introducing the characteristic claw extractor. Previous Mausers were, like many modern bolt guns, push-feed operated; the bolt simply stripped a round from the magazine and pushed it into the chamber. The new Mausers big claw extractor engaged the extraction groove on the cartridge and guided it into the chamber directly, making for what most bolt gun mavens consider a more reliable feed; the downside of this system is that one cannot simply drop a round in the action and close the bolt. Loading a single round requires the shooter to place the round into the magazine so the bolt can engage it as designed.

Most of the new Mausers were chambered for the new 7x57mm rimless cartridge, a low-recoil, high-velocity round that would prove popular in martial circles and, later, in the game fields. In fact, of all the Mauser cartridges, the 7x57mm alone remains popular among American shooters to this day. The first models turned out by Mauser went to Spain, and these rifles still are often referred to generically as “Spanish Mausers.” But many of these guns were made and sold all over, seeing service with the armies of Belgium, Brazil, Chile, Congo, the Ottoman Empire, and Serbia.

In Sweden, the Carl Gustaf works turned out what may be the finest of the pre-98 rifles in the M94 and M96 Swedish Mausers, chambered for the excellent 6.5x55mm Swede cartridge. Many Swedes have been imported into the States, and as they are easily converted into lightweight sporters, make excellent rifles for deer-sized game.

In 1898, though, Paul Mauser produced his finest work.

The 1898 (or, simply, the 98) was the culmination of Mauser’s design work. Most bolt-action sporters today are adaptations of the 98 Mauser. This new action had a larger receiver ring with a stout reinforcing web, a solid bolt with the usual two big locking lugs but also a third safety lug at the rear; the bolt shroud was larger and had a large flange to direct hot gases away from the shooter in the event of a case rupture.

There was one other major innovation. Before the 98, Mauser's actions combined the initial lift of the bolt handle with a slight camming action to initiate the extraction of a fired round. When closing the bolt, the shooter was required to push the bolt home against the mainspring, thus cocking the piece.

The 98 changed that, using the camming action of the bolt to cock the striker on opening rather than closing. This made the operation of the action faster and more secure, and allowed the force of the run forward to be devoted to chambering the next round.

The 98 changed that, using the camming action of the bolt to cock the striker on opening rather than closing. This made the operation of the action faster and more secure, and allowed the force of the run forward to be devoted to chambering the next round.

It was with this action and the Gewehr 98 rifle built around it that Paul Mauser finally regained the attention of the German Army. Germany entered the Great War fielding this long, heavy, powerful rifle and its 7.92x57mm S-bore (.323) cartridge; over nine million Gewehr 98s were made, many millions more rifles were built around the basic M98 action, and the 98 Mauser action would become the basis for martial and sporting rifles all over the world. I have in the past mentioned my favorite hunting rifle, built on a 98 Mauser action made by DWM in Berlin around 1911 on contract for Brazil; if you own a Winchester Model 70 or a Remington 700, you are shooting a rifle closely modeled after the 98 Mauser.

Mauser produced a wonder, but across the English Channel, the Brits were developing a gun that may well have surpassed it as a pure battle rifle.

Meanwhile, in Britain

In 1879, the British Army was looking to replace their single-shot black-powder Martini-Henry rifles with something more modern. Enter a sporting chap named James Paris Lee. Lee had developed a practical box magazine that allowed a shooter to load multiple rounds with a new device called a stripper clip, or to simply stuff single rounds into the magazine.

Working with another inventor named William Ellis Medford, the two came up with a bolt-action repeater with an eight-round (later ten-round) magazine, locking lugs on the rear of the bolt, and a cock-on-closing mechanism similar to the pre-98 Mausers, the thinking in Blighty being that the cock-on-close action was quicker to operate.

My personal experience is just the opposite, but I’m just one guy, after all.

While Lee-Enfield’s short bolt throw (60 degrees compared to the Mauser’s 90) had probably as much to do with that quick operation as the action, nevertheless, the new rifle proved acceptable, and in 1888, after nine years of tests, the British Army adopted the Lee-Metford magazine rifle and its .303 rimmed cartridge.

Important note: In the last issue, I incorrectly identified the Italian Vetterli as the first mass-produced bolt gun with a box magazine; as a sharp-eyed reader noted, the Lee-Metford preceded it.

The Lee-Metford rifle would, however, only stay in primary service until 1895, when a modified version was adopted. This was the Short Magazine Lee-Enfield (SMLE) rifle, a ten-shot magazine-fed adaptation of the Lee-Metford built at the Royal Small Arms Factory in Enfield.

The Lee-Enfield would prove successful indeed as a battle rifle. Its ten-round capacity was double that of most magazine rifles of the time. Like its competitors, it would be loaded by stripper clip or with single rounds; unlike them, the magazine could be removed from the rifle and replaced with a loaded one, although this practice was not encouraged at the time due to fears that the common soldiery would simply lose the detached magazines.

Over seventeen million Lee-Enfield rifles would be manufactured in several variations.

But about this time, across the Atlantic, the United States Army was finally thinking of moving past single-shot black-powder breechloaders, and another Lee design would be part of that calculation.

The Americans Upgrade

In 1894, the same year the immortal Winchester Repeating Arms Company brought out the immortal 1894 lever gun, the U.S. military was looking around for a smokeless powder repeater to replace their single-shot black-powder Springfields. The Navy chose to adopt a semi-rimmed 6mm cartridge, and the Navy Test Board invited manufacturers to submit repeaters for their testing at the Naval Torpedo Station.

After screening a mess of rifles, including no less than five Remington bolt-action prototypes, the Navy settled on a straight-pull bolt gun designed by no less than James Paris Lee.

The M1895 Lee Navy rifle had a fixed box magazine that was loaded with a five-round en bloc clip, which had the advantage of speedy reloads but the disadvantage of not being able to top off the magazine with single rounds. Nevertheless, the Lee was an interesting design and in 1895, the choice of the small-bore cartridge was unprecedented.

That cartridge design survives today, incidentally, necked down to .22 caliber, as the .220 Swift.

The Lee Navy rifle only ended up in front-line service for three years, though, as in 1898, a board of Army, Navy, and Marine officers determined a standard rifle was in order.

The story of the first inter-service standard turn-bolt repeater begins in Norway with a gun designer named Ole Herman Johannes Krag and a gunsmith named Erik Jørgensen. Krag had been in the small-arms business since 1866 and was unsatisfied with the tubular magazines in military rifles of the time; he sought out Jørgensen to design something new. What they came up with was a solid bolt gun with a 5-round magazine that loaded through a loading gate on the right-hand side of the rifle. This novel loading system had two big advantages: It allowed for topping up the magazine with single loads and allowed for fast reloads as loose rounds could be dumped into the open magazine gate, and when the spring-loaded gate was closed, the rounds would automatically be aligned for proper feeding.

Denmark had adopted what became the Krag-Jørgensen repeater in 1889. In 1892, after a competition among 53 rifle designs, the U.S. Army, Navy, and Marines adopted what would be called the M1892 Krag rifle, firing the .30 Government cartridge, later known as the .30-40 Krag.

The Krag was a good, solid, reliable rifle. About half a million were manufactured by the Springfield Armory between 1892 and 1907. Krag repeaters saw service in the Spanish-American war, the Philippine Insurrection, the Boxer Rebellion, and the Mexican Revolution, and as a reserve weapon in the Great War. But during the Spanish-American War, the Krag performed poorly against Spanish troops armed with 1893 Mausers and their 7x57mm cartridge. The Army determined that a more modern rifle was in order.

Thousands of Spanish Mausers were surrendered by Spanish soldiers in Cuba. Many of those found their way to Massachusetts, where Springfield Armory gunsmiths examined that design and came up with an American counterpart. Features of the 93 and 98 Mauser patterns were combined along with some American requirements, like a knurled cocking knob on the striker rear and a magazine cut-off. A new, powerful rimless cartridge was designed that fired a 220-grain round-nose jacketed bullet at about 2200 fps, but after three years and a distinct lack of zap, the original .30-03 round was replaced by a new round with a slightly shorter-necked round firing a 150-grain spitzer bullet at about 2800 fps. Now the combination of rifle and cartridge was complete: The M1903 Springfield and the Ball Cartridge, Caliber .30, Model of 1906, or simply the .30-06, which remains today one of the most popular centerfire rifle cartridges in the world; it has been claimed that more North American big game has been killed with .30-06 rounds than by all other centerfire rifle cartridges combined and while I have never seen numbers to support that, I don’t find it outside the realm of possibility.

This rifle would be the primary weapon of the U.S. Army and Marines when the U.S. entered the Great War in 1917.

In Russia

The story of bolt-action repeaters in Russia is the story of the Mosin-Nagant.

Russian troops were armed with the Berdan single-shot rifle when they went off to fight the Ottoman Turks in the Russo-Ottoman War of 1877. Unfortunately for them, the Turks were equipped with Winchester repeaters. Although Russia eventually won that conflict, the Russian troops fared poorly in direct action against the fast-firing Turks, and this was enough to make even Russian military planners realize a change was in order.

In 1889, the Russian Army evaluated three rifles: Captain Sergei Ivanovich Mosin’s “3-line” (.30 caliber) rifle, Belgian Leon Nagant’s “3.5-line” (.35 caliber, more or less) rifle, and a third design by one Captain Zinoviev. Trials continued until 1891, when the officers in charge of the evaluation commission decided to combine the best features of the first two rifles, resulting in the M1891 Mosin-Nagant rifle.

The Mosin-Nagant was certainly a robust piece, even if most examples I have seen lacked the fit and polish of German, British, and American-made rifles of the time. The M1891 used two big opposed front-locking lugs like the 98 Mauser, a fixed single-stack magazine like the 89/91 Mausers, and a push-feed system.

Like the Kalashnikov rifles that succeeded it, the Mosin-Nagant was stoutly built, made to withstand slapdash maintenance and hard use by poorly educated peasant soldiers. Its 7.65x53R cartridge was on par with the German, British, and American rounds, and the Russian rifle, however rough in design, certainly stood the test of time. Like the AK, it was in service all over the world; also, like the AK, it is impossible to know precisely how many Mosin-Nagant variants have been built, but the number probably approaches forty million.

And Then This Happened

There is a saying among bolt gun aficionados that among Great War battle rifles, “The Mauser is the best hunting rifle, the Springfield the best target rifle, and the Lee-Enfield the best battle rifle.” (The Mosin-Nagant, on the other hand, made the best tent pole.) The Great War provided us with plenty of evidence of how these three guns worked in action, but truisms aside, the impact of these pieces would go well beyond the war, as more and more "weapons of war" were adapted for civil uses.

See Related: Ohio Republican Senate Candidate Previously Endorsed California-Like Gun Control Laws

Judge Allows Challenge to New York 'Assault Weapon' Ban to Proceed

With the breakout of the Great War, the Allied powers and the Triple Alliance were all equipped with bolt guns. While the European powers went into the fray well-equipped, the British found themselves struggling to produce enough Lee-Enfield rifles for their troops.

Enter that industrial powerhouse across the Atlantic. Great Britain’s estranged offspring, the United States, was about to bail out the Brits (not for the last time) by producing a new bolt rifle for the .303 British round – and later, in 1917, another version of that same rifle to supplement the standard-issue Springfield. The result of that was almost five million American doughboys who became accustomed to shooting bolt guns at the detested Hun and an American firearms industry that was suddenly proficient at building bolt guns. More on this in a later installment.

This trend would continue through the inter-war years. While the American bolt gun trend started with service rifles, the various gun companies here would quickly bring out their bolt-action sporters, and competition among the companies resulted in a great variety of rifles available for sale.

Americans then and now love guns. Plenty of shooters then and now like to be in on the latest big thing, and after the Great War and on into the rest of the 20th century, bolt-action sporters were the New Hotness. Not to be left out, European manufacturers weren’t about to miss this growing market either. But that, too, is a story for a later installment.