With all the fuss over pols who know nothing about guns whining about gun control laws, and with all the hooraw about “assault weapons,” it’s easy to overlook the whole rest of the world of guns. Personally, when it comes to rifles, I’m a big fan of accurate, scoped bolt guns; they are reliable, powerful, and have a lot of history behind them. And in this world, one old cartridge really stands out: The grand old .30-06. (I would list the equally grand old .30WCF -- 30-30 -- as a very close second.)

The .30-06 Springfield, originally known as the Caliber .30 U.S. Govt Model of 1906, is almost certainly the standard by which all North American center-fire, big-game cartridges must be judged. This round not only has great advantages of versatility, being able to be loaded for any game from groundhogs to moose; it has also served as father and grandfather to more center-fire rifle cartridges than any other. I’ve often said that if you can own only one center-fire rifle, buy a .30-06. This great old round has long been the gold standard for all center-fire, big-game rifle cartridges. Here’s why.

The Forerunners

The influences that led to the genesis of the .30-06 come were twofold.

First:

When the last decade of the nineteenth century began, the United States Army was still using the 1873 “Trapdoor” Springfield single-shot rifle and its .45-70 black powder cartridge. When the .45-70 was new, it was considered a “small-bore” round by the standards of its day – “its day” being the 1870s. In 1890, smokeless powder was the new standard. In Germany, the GEW88 rifle was shooting the new 7.92x57mm smokeless-powder round. In Britain, the Lee-Metford rifle and its .303 round were the new hotness.

The United States Army had some catching up to do.

What they did to catch up, initially, was to adopt a foreign-designed rifle. The Krag–Jørgensen was a rather odd bolt gun, originally designed by the Norwegians Ole Herman Johannes Krag and Erik Jørgensen in the late 19th century. In 1892, the Army held a design competition, testing several different rifle designs before settling on what would become the Springfield Model 1892–99 rifles.

The “Krag” was something of an oddball by today’s reckoning. The Army had specified a couple of things in their first repeater, namely a magazine cut-off to allow the use of the gun as a single shot while reserving the rounds in the magazine. Another requirement was that the rifle’s magazine should allow “topping-up” the piece with single rounds.

The Krag met those requirements with a magazine that loaded through a spring-loaded gate on the right-hand side of the rifle. This was an interesting arrangement, as one could drop fresh rounds into the magazine without opening the bolt, leaving the rifle in a ready-to-fire state while reloading. The action was smooth in operation, and in fact, was popular as the basis for custom sporters until right around World War II.

To go along with the new rifle was the Army’s first .30 caliber smokeless powder cartridge. The .30 US Army, also known as the .30-40 Krag, was adopted in 1892 along with the first iterations of the Krag rifle. This was a rimmed cartridge launching a 220-grain bullet at about 2,000 fps. This wouldn’t blow up many skirts today, but at the time, this was a respectable figure.

The Army now had a reliable repeater firing a smokeless powder round, but they weren’t done yet.

Second:

When the Springfield Armory began considering a new service rifle and cartridge, they clearly looked very hard at the products of the Mauser-Werke in Oberndorf. The 1892 competition had evaluated the 93/95 pattern Mausers, a weaker, small-ring design with a cock-on-close bolt that required the soldier to push the bolt closed against the mainspring.

Just a few years later, though, Mauser had made a great leap forward, that being the big, tough Model 98 action.

Germany’s Gewehr 98 rifle had a lot going for it: A strong, reliable action, a completely enclosed box magazine that loaded from stripper clips but could still be “topped up” with single rounds, and a slick, rimless, powerful smokeless powder cartridge.

Also, in 1898, the United States entered a little fray that became known as the Spanish-American War. During that fracas, the Spanish troops were armed with M1893 Mausers, the aforementioned small-ring design which had its weaknesses – but the cartridge they were using was not one of those weaknesses. The Spanish had adopted the 7x57mm round, which fired a 173-grain bullet at 2,300fps. The Spaniards, loading their five-shot 93s with stripper clips, kept up an impressive rate of fire at considerable ranges. The 7x57mm round developed rather higher pressures than the .30US, pressures that the Krag action wasn’t up to.

If the U.S. was to match or (preferably) exceed the performance of the Spanish Mausers, a new design was required.

The New Rifle

The genesis of the new Springfield rifle began with a prototype Model 1900 based on the M1893 Spanish Mauser. This design was quickly rejected. In 1901, a new prototype, the Model 1901, was produced; this version had a cock-on-open bolt, a Mauser-style magazine with a magazine cutoff, a 30-inch barrel, and the sights from the Krag rifle. With this version, Springfield came closer to meeting the Army’s requirements, but it took two more years to finalize the design.

The result was the United States Rifle, Caliber .30, Model 1903, which became known as the “’03 Springfield.” The new rifle had a 24” barrel, the Mauser-style staggered box magazine with a cutoff, new sights, a knurled knob on the striker to allow manual cocking, and the receiver was adapted to feed the internal five-round magazine with stripper clips. The ’03 was so clearly patterned after the M98 Mauser that Mauser-Werke sued the U.S. government and was awarded $250,000 in royalties. The 1903 also came originally with a rather fragile rod-type bayonet, which after protests by the Army and veterans of the Spanish-American war (not least of whom was one Theodore Roosevelt) was exchanged for a stouter, blade-type bayonet.

It was the cartridge, however, and not the rifle that would prove to have a lasting impact on the American shooting scene.

The New Cartridge

The .30-06 wasn’t the original cartridge for the new Springfield rifle.

One might note that the rifle is the Springfield 1903, while the cartridge is the Model of 1906. There’s a three-year gap between rifle and cartridge, and that gap was filled with the .30-03. Originally called the .30-45 for its 45-grain, smokeless powder charge, the .30-03 fired a 220-grain round nose bullet at about 2,300 fps. This was not a significant leap above the .30 US cartridge and the new round’s tepid velocity resulted in a less-than-impressive trajectory. The .30-03 round also developed high pressures and temperatures on firing to push that heavy bullet even to the modest velocity achieved, resulting in excessive barrel wear with the steels available at that time. The 220-grain pill was not aerodynamic, which also had negative effects on performance at range.

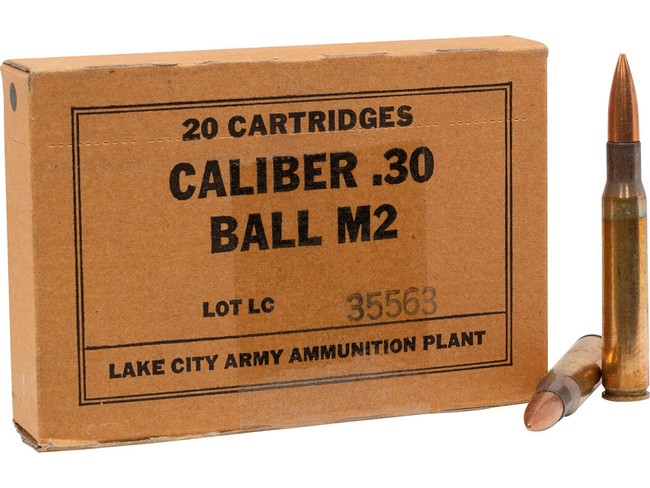

So, in 1906, a new version was introduced. The “Cartridge, Ball, caliber .30, Model of 1906,” which quickly became known as the .30-06, was based on the .30-03 but kicked things up several notches. The .30-03 case neck was shortened by .046 inches, and a new cooler-burning powder was used along with a 150-grain spitzer (pointed) bullet.

Now, the United States had a world-beater. Existing Springfield rifles were ordered returned to the Springfield Armory to be refitted, which was accomplished simply by removing the barrels, turning off a portion at the chamber end, rethreading, refitting, and rechambering. The .30-06 was adopted not only for the various Browning machine guns and the Browning Automatic Rifle but also in the Pattern 17 Enfield that was built to equip troops deploying to France in the Great War. And, of course, beginning in 1934, the .30-06 saw action in what George Patton described as the greatest battle implement ever devised by the mind of man: The M1 Garand.

The new cartridge had a lot going for it. The case design was near-perfect; the slight taper to the case made for reliable feeding, so much so that the design became the pattern for the .50 Browning Machine Gun case along with the 20mm and 30mm cannon cases.

Winchester quickly picked the cartridge up for the M1895 lever gun, along with the Model 54 and later, the Model 70 bolt guns. Remington chambered it for the Model 30 and later, the Model 721 bolt guns, along with the later 740 auto and 742 pump-action rifles.

In fact, there are so many rifles in so many action types that the format of this article precludes listing them all here. But it is said that more North American big game has been killed with the .30-06 round than with all others combined, and while the existence and popularity of the .30WCF makes me question this, I would easily agree that the .30-06 has been and remains the most popular center-fire rifle cartridge for North American big game.

Offspring

In both commercial and military use, the .30-06 was a huge success. However, the superior design of the case, along with the post-war availability of cheap surplus brass, led to the development of a plethora of sporting cartridges based on the .30-06 case.

Full-length commercial offspring include:

- .25-06 Remington

- .270 Winchester

- .280 Remington

- .338-06 A-Square

- .35 Whelen

The .30-06 case also became the foundation for the post-WW2 7.62 NATO round, adapted (there are some differences in case structure and loads) into commercial use as the .308 Winchester, along with its family of offshoots:

- .243 Winchester

- .260 Remington

- 7mm-08 Remington

- .338 Federal

- .358 Winchester

And shall we mention wildcats? From the .22-06 to the .30-06 Ackley Improved to the .400 Whelen and everywhere in between, the .30-06 case has inspired more tinkering than we could only begin to describe here.

But it is said that a man may be judged by the caliber of his enemies, and so a rifle cartridge may be judged by the quality of its competition.

The Competition

In its heyday, the .30-06’s military competition included such rounds as the 7.7mm Arisaka, the 7mm and 8mm Mauser rounds, and the .303 British cartridge. But in the civilian market, things were a bit more complicated.

Returning servicemen brought a fair number of captured Mausers and Arisakas with them; surplus sales resulted in more of these guns being imported. Both the 7.7 Arisaka and the 8mm Mauser rounds yielded roughly .30-06 level performance; so, those cartridges were loaded by American ammunition manufacturers and saw some level of popularity, especially among budget-conscious shooters.

The real competition for the .30-06 came with the early 20th-century advent of the belted magnums, based on the excellent .375 H&H case, and the mid-century advent of the various Eargesplitten Loudenboomer rounds. These cartridges, including my own favored .338 Winchester Magnum, did yield significantly more power than the .30-06, but that power came at a price; one either suffered increased recoil and report, or carried a significantly heavier rifle to deal with the kick. My own .338 Mag, fully loaded, and with scope and sling, weighs in at a tad under 10 pounds.

Even so, while the magnums continue to be popular today, no other single round has really challenged the century-plus supremacy of the .30-06.

Today

Today, at 117 years of age, the .30-06 remains as it was, probably the most popular center-fire big-game cartridge in North America. Properly loaded and handled, as I mentioned earlier, it can handle any game from woodchucks to moose; if one loses ammo to some mishap, you can get at least some kind of rounds in almost any Walmart or hardware store from Fairbanks to Tallahassee.

All these factors combine to make the .30-06 Springfield a gold standard. It was and is the standard by which all other center-fire big-game cartridges must be judged and is likely to remain so throughout most of the 21st century.

This story was updated to reflect that a gun discussed above was a GEW89, not a GEW98.