Every once in a while I, and my colleagues, take a break from bringing Writs of Fire and Sword to the Democrats and write about something that interests us personally. This is one of those occasions.

Up until recent years, after progressives gained control of academia, most Americans knew that the Japanese bombed the US military complex at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, on December 7, 1941, and that we didn’t deserve to be bombed. On that morning some 3500 Americans, military and civilian, were killed and wounded.

One of the most tragic stories though is the final deaths from the Japanese attack were not claimed until December 23, sixteen days after the event.

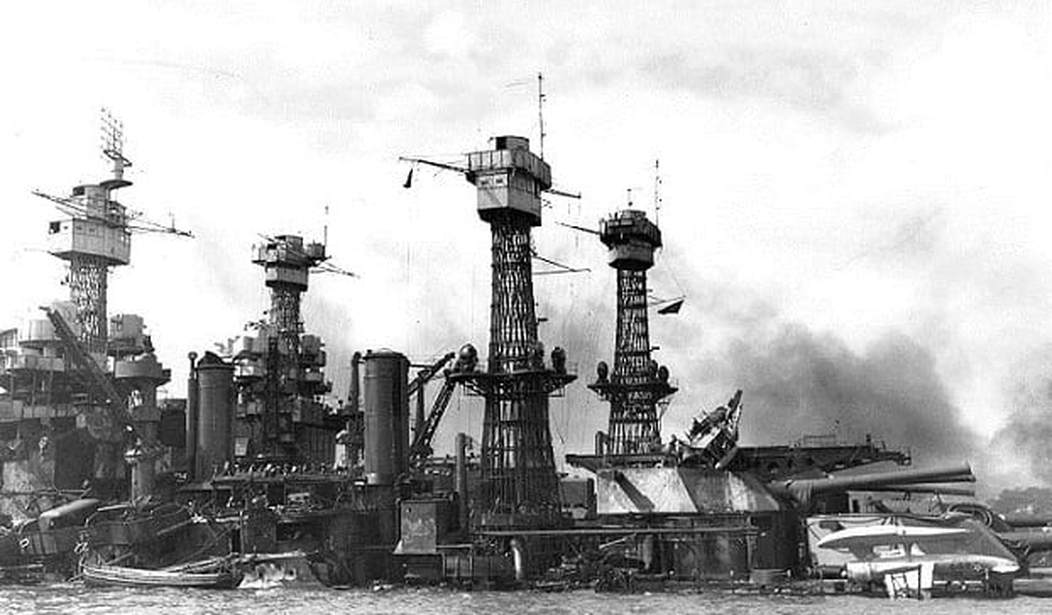

On the morning of December 7, 1941, the USS West Virginia (BB-48) was moored on Battleship Row outboard of the USS Tennessee (BB-43). She was a Colorado-class battleship, launched in 1921, and represented state of the art in US naval architecture. She’d been designed to slug it out with other battleships holding her place in line of battle. Her vulnerability to air attack wasn’t a great concern. When the attack passed and the damage was assessed, the West Virginia was sunk. She rested in 36-feet of water with her superstructure exposed and accessible.

Much of her port side had been ripped open by as many as eight Japanese torpedoes, and her rudder had been blown off by another. The battleship’s multi-layered anti-torpedo side protection system had been completely broken through, making it impossible to raise the ship without the use of extensive external patches. These structures, which covered virtually the entire hull side amidships, extended vertically from the turn of the bilge to well above the waterline. The patches were assembled in sections, with divers working inside and out to attach them to the ship and to each other, and were sealed at the bottom with some 650 tons of concrete.

As with other salvaged ships, West Virginia required extensive weight removal to allow her to be floated into drydock. Among the items removed were some 800,000 gallons of fuel oil, projectiles and powder for her sixteen-inch guns, and other supplies. Also removed were two unexploded Japanese bombs.

As the damage control parties moved onto the West Virginia they heard something strange:

At first, everyone thought it was a piece of loose rigging slapping against the wrecked hull of the USS West Virginia.

Bang. Bang.

To the survivors on land, it was just another noise amid the carnage of Pearl Harbor a day after the Dec. 7, 1941, attack. Like the sound of fireboats squirting water on the USS Arizona. Or the hammers chipping into the overturned hull of the Oklahoma.But they realized the grim truth the next morning, in the quiet dawn. Someone was still alive, trapped deep in the forward hull of the sunken battleship.

Bang. Bang.

The Marines standing guard covered their ears. There was nothing anyone could do.

Three young sailors, Ronald Endicott, 18; Clifford Olds, 20; and Louis “Buddy” Costin, 21, were trapped in an airtight storage room below water. They had access to a supply of potable water and emergency rations but it proved a cruel gift.

No one wanted guard duty that put him within earshot of the West Virginia, especially on quiet nights. They would do anything to trade posts so they wouldn’t have to hear the desperate – almost tireless – cry for help.

“God, I can’t go by that ship anymore,” a buddy told Marine Dick Fiske.

To attempt to cut an access route to the submerged storage room risked the acetylene torches causing a catastrophic explosion on the way in and, because the storage room was submerged, once the compartment was breached there was a good chance it would flood before the men could be extracted.

Eventually the bangs ceased. When the West Virginia was raised, months later, work parties reached the storeroom:

After months of picking bodies from the West Virginia, sailors removed the remains of three men from storeroom A-111, clad in their blues and jerseys. They were carried away in heavy canvas bags drawn tight at the top.

The clues left in the dry storeroom hinted at a horrifying demise. Flashlight batteries littered the floor. The manhole to a supply of fresh water had been opened. Emergency rations had been eaten.

And the calendar. A foot high, 14 inches long. A red “X” scratched through the dates from Dec. 7 through Dec. 23.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member