Missouri Gov. Mike Parson speaks after being sworn in as the state’s 57th governor following the resignation of Eric Greitens Friday, June 1, 2018, in Jefferson City, Mo. Parson moved from lieutenant governor to governor after Greitens stepped down Friday amid investigations of his political and personal life.(AP Photo/Jeff Roberson)

A comment from a family member the other day about the Governor of Missouri, Mike Parson, “waffling” regarding issuing a stay-at-home order in response to the coronavirus got me to thinking about something: I’ve seen media criticism regarding those governors who’ve declined to issue statewide stay-at-home orders and those who were later in doing so. Presumably, that criticism is borne of the belief that the failure to implement such orders will result (or has resulted) in increased numbers of infections and, possibly, deaths.

It will likely come as little surprise that I’m a defender of Governor Parson on this front. (Full disclosure: I was at my county’s Lincoln Day celebration the evening Missouri’s first case of coronavirus was announced. The Governor was slated to be there but was called away in light of the announcement.) As the pandemic has unfolded, Gov. Parson has, in my observation, maintained a steady, calm approach, initially leaving it local officials to make the call best suited for their respective communities, though he did eventually issue a statewide order which took effect April 6th. (Note: St. Louis City and St. Louis County issued stay-at-home orders that took effect on March 23rd; adjacent St. Charles County — where I reside — followed suit the following day.)

Parson’s (and other governors’) decision to hold off met with some media criticism. (See, e.g., here and here. My colleague, SisterToldjah, also highlighted some of that criticism here.) Though he was giving regular updates regarding the state’s response to the situation, I was, frankly, gobsmacked by the number of people howling at him every time he tweeted about it to shut the state down — people who, undoubtedly, do not agree with his politics and would never vote for him. Yet, they were flat-out demanding that he restrict their freedom; shut the whole state down — consequences be damned. This, while much of the state had few — if any — cases.

📊 COVID-19 update for April 7: 3,037 positive patients with 508 hospitalized patients. We are saddened to report we have lost 53 Missourians to COVID-19.

To learn more about Missouri’s COVID-19 response and statistics, visit https://t.co/V6es2EUkO0.#COVID19 | #ShowMeStrong pic.twitter.com/c8RhFxt2W4

— Mo Health & Sr Srvcs (@HealthyLivingMo) April 7, 2020

So…like I said, it got me to thinking: What was going on in the states around Missouri? (Little bit of trivia: Missouri and Tennessee have the distinction of being the two states with the most border states — eight.) And, perhaps more importantly, what was going on in states with early stay-at-home orders versus those with later (or no) stay-at-home orders?

So, I got to digging. I pulled together stats for Missouri and each of its bordering states. I was particularly interested to compare Missouri and Illinois — for a couple of reasons: First, and foremost, I live and work on the Missouri/Illinois border, so am fairly attuned to what’s going on in the bi-state area. Second, Illinois was one of the earliest states to implement a statewide shutdown. Third, Missouri being a red state and Illinois being a blue state adds a certain degree of…intrigue.

I wanted to take into account more than just pure COVID-19 numbers, so I also pulled population numbers, the population of each state’s larges metro area, and the political affiliation of their governors and makeup of their legislatures. I started with Missouri and its eight border states. And then, for good measure, I added in the four other “holdout” states — Utah, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Wyoming (whose approach to social distancing I wrote about last week.)

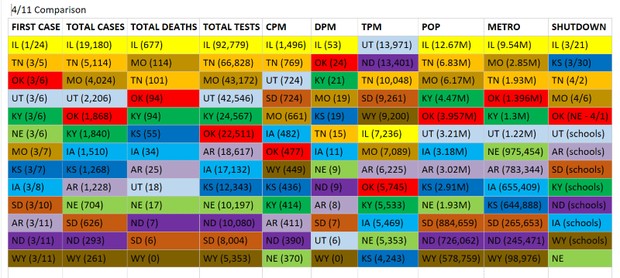

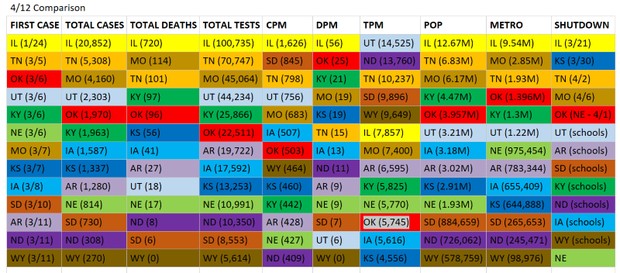

I even pulled together some fancy tables to reflect the data. (These tables reflect the data for 4/11 and 4/12 – current as of 10:30 pm CDT. The virus totals were pulled from worldometers.):

From left-to-right, the tables track: Date of first case; total cases; total deaths; total tests; cases per million people, deaths per million people, tests per million people, statewide population, largest metro area population, and date of statewide shutdown (stay-at-home order).

I did not include the political affiliation/makeup information in the tables (largely because it doesn’t result in a numeric rank so as to make much table-sense.) However, I thought it somewhat interesting to note that of the 13 states surveyed, only three have Democrat governors (Illinois, Kentucky, and Kansas), and only one has a majority-Democrat legislature (Illinois.) In fact, nine of the states in question have Republican super-majorities.

So, what stands out in all this? Well, for one thing, Illinois. It basically runs the table, so to speak, save for tests per million people. (Interestingly enough, the states with the highest number of tests per million are (other than Tennessee) those without stay-at-home orders in place.) Illinois has the highest number of cases (by far), the highest number of deaths (by far), the highest number of tests and, perhaps not surprisingly, the highest number of cases and deaths per million people. Of the states surveyed, Illinois also has the largest population (by far) and the largest metro area population (by far). Keep in mind — looking at the cases and deaths “per million people” factors in that population differential.

Most importantly, Illinois was one of the earliest states to issue a statewide stay-at-home order. Governor J.B. Pritzker issued the order which went into effect on March 21st. While Illinois had one of the earliest reported cases of coronavirus (the first case was reported on January 24th), the number of cases remained low through the early part of March. As of March 12th, there were only 32 cases. On March 21st, the day the order went into effect there were 727 cases in Illinois. Obviously, there was a fairly significant jump in mid-March and one might surmise that Pritzker’s decision was a reasonable reaction to the situation as it was developing. Fair enough.

But if that’s the case, then what justifies the criticism of other governors for doing the same thing in relation to their respective states? Or are we just going to subscribe to the notion that all states are exactly alike? That their needs and circumstances are identical? In which case, why even have governors making these decisions? Why not just insist that King President Trump decree a nationwide lockdown? Never mind the fact that the vast majority of states aren’t experiencing the level — or rate — of infection and deaths that Illinois is.

Some might contend that it’s only a matter of time until the infection spreads and the rate of infection in other states matches that of Illinois. But if that were the case, then wouldn’t we already see states around Illinois experiencing similar numbers? Conversely, if statewide stay-at-home orders were the key, wouldn’t we see a lower rate of infection in the states that issued them early than in the states that issued them late – or haven’t at all?

But that’s not what we’re seeing. In either respect. States immediately adjacent to Illinois – particularly the northeast quadrant, where Chicago (and the vast majority of Illinois cases) are located – don’t have similar infection numbers or rates. Wisconsin? 3,341 total cases, with 587 cases per million people. Indiana? Indiana is a closer call – but even they have a lower rate (1,194 per million people) – and a lot of those are centered largely around Indianapolis, not Illinois-adjacent areas.

Which brings me back to Missouri – Illinois’ neighbor to the west. Where is Missouri in relation to Illinois? One-fifth the total number of cases, one-sixth the total number of deaths, a case per million rate of 683 (versus Illinois’ 1,626) and deaths per million at 19 (versus 56). And this, despite a stay-at-home order that came 16 days later.

And what of those states without a stay-at-home order at all? Eight of the thirteen included in this analysis remain without one. Which are the states on the lower end of the caseload and infection rate? Seven of those eight states. Utah appears to be the outlier here. However, Utah also has a decent-sized population and, perhaps more significantly, the highest rate of tests per million people – which may simply mean that a higher number of tests = a higher number of cases. You’ll note, they maintain one of the lower numbers of total deaths and the second-lowest number of deaths per million people.

All of which is to say: There doesn’t really appear to be much correlation between the implementation of a statewide stay-at-home order and infection or death numbers or rates. Rather, the clearer correlation appears to exist between population density and infection/death numbers and rates — among the states and within each state. (So…wait…you mean this virus is no respecter of state boundaries or laws, but rather, hops from person-to-person more easily in more densely populated areas? Knock me over with a feather!)

Oh, and while we’re drawing conclusions, one might note that, while the first two stay-at-home orders in the states studied came from Democrat governors, the infection/death numbers and rates differ between those two significantly. Illinois is hurting, while Kansas is doing okay. Keep in mind — Illinois has a population of 12.67 million, while Kansas only has 2.91 million. Kentucky, which has the third Democrat governor, sits in the middle of the pack. It also has no statewide stay-at-home order (although apparently its Governor doesn’t take all that kindly to church congregations…well, congregating. READ: Federal Judge Shocks Many When He Informs Louisville Mayor That the US Constitution Applies There and Churchgoers Show up for Easter Services, Met With Nails and the Police After Governor Forbid Public Gatherings.)

Maybe…just maybe…what all of this means is that each state’s governor is better situated to assess his/her state’s respective needs and appropriate response to this pandemic. It may even mean that a governor’s decision to hang back and let local officials make the best call for their respective constituencies isn’t such a bad thing after all. Go figure!

Join the conversation as a VIP Member