As regular readers of this Memories series know, and new ones will soon discover, I enjoy sharing stories from my life and decades as a journalist. (All the links are below.) Especially if the stories seem to tell us about more than one immediate event.

Here’s one about a woman in the world’s oldest profession who was seeking entrance to the world’s second-oldest profession.

She was Beverly Harrell, a brothel owner in a Nevada county where paid sex was legal. She was running against a fellow Democrat for entrance to a different kind of house, the state legislature.

He was Don Moody, a local businessman who married his high school sweetheart. Don admitted he was puzzled on how to campaign against a hooker who bought ads in the high-school yearbook.

Beverly – she said I should use her first name because it’s more intimate – owned the Cottontail Ranch, a pack of comfy mobile homes connected by catwalks amid Nevada’s 110,00 square miles of desert.

She stood four-foot-11 in her false eyelashes, blunt talking, and called herself a Jewish girl from Brooklyn via California. “Make yourself comfortable,” she said.

(But I didn’t, Hon. I didn’t.)

Legal schmegal, prostitution has always flourished in Nevada. Antique local records near Beverly's business show that in the 31 days of December, 1907, one dozen women in the Santa Fe Saloon entertained 3,667 customers. Do the math on that.

Prostitution was so normal in Lida Junction when I visited that another house of good repute openly sponsored a men’s bowling team. And the Cottontail was the best sales stop ever for Helen Cozard, the Avon lady.

The Ranch was slow the afternoon I visited. But tired, tense travelers parked their cars or airplanes to seek comfort and understanding with partly-clad solace at the bar, by the bubbling bath, or in one of the lush rooms. Prices were determined by kitchen timers labeled Debbie, Lori, Candy. MasterCard accepted.

“Madams are businesswomen,” Beverly said “and I'm a good one.” Business acumen, in fact, became a campaign issue.

Don ran a liquor store, a gas station, and a different kind of trailer court. He said his business was good. But he claimed Beverly’s bordello success did not necessarily qualify her for the other house in Carson City.

“She's running a business with no inventory,” he said, “selling the product and still having it. Why shouldn't she be successful?”

As always in politics, honesty was an issue. Don noted his clean record of service on the county commission and stressed his Nevada background. The prosperous madam said, honestly, she was guaranteed clean because she didn’t need anything anyone might offer.

“I cannot be bought,” said Madam Harrell. “Politically, I mean.”

Anyone who spent any time in Chicago back in the day or read some 1,100 newspapers around the world knew Eppie Lederer, an Iowa girl much better known as Ann Landers.

She was the premier advice columnist of the time, read by an estimated 90 million at her peak. She began answering reader questions in 1955 and continued until her death in 2002. (Her twin sister wrote the Dear Abby advice column.)

Ann was such a Chicago celebrity that when she changed newspapers from the Sun-Times to the Tribune, it was front-page news.

Ann received hundreds of letters a day from people sincerely seeking answers to questions that mattered to them. The hardest part was wading through them all. Ann liked to work from home in a bathtub full of warm water with her typewriter on a board in front of her.

I asked her once what she got the most mail about. “Oh, that’s easy,” she said, “the toilet paper column.”

Dear Ann, she said the letter began, my husband and I are arguing over toilet paper. Should it roll off the top or the bottom?

Ann said the answer was easy for her to write. However, she was totally and completely wrong. She said toilet paper should roll off the bottom.

And did she ever hear about it!

I grew up near a small Ohio farm town that’s now a bedroom suburb for Akron and Cleveland. Tractors with huge muddy wheels parked by the stores on Main Street. Even miles out of town, you could hear the noon siren. And if it sounded at any other time, that meant fire or, worse, tornado.

So, years later, when I heard state noise-pollution people had silenced the noon whistle in Canton, Ill., I knew that was Big News. The shocking news came long after the local paper’s deadline. But for something so important, the presses were halted.

Like thousands of communities across the Heartland, the regular whistle or siren is an important marker, a regular, predictable sign that life is proceeding according to normal schedule. Loud and comforting.

People woke up to the early whistle atop the International Harvest factory. It was said to be the same as the one on the Lusitania. Work shifts started and ended by the whistle. Meal preparations were begun by it. Children in the most secret of clubhouses had to head home.

The local milkman was deaf. But if he could hear the whistle, he knew rain was coming and warned the women on his route not to hang out wash.

Canton is a very friendly place unless, that is, you’re trying to shake things up. It’s the kind of community where even the movie's popcorn stand posted a warning: “Caution—Salt pours fast.”

The factory whistle was a community bond. Everyone heard it at the same time. So, when the whistle didn’t blow, everyone didn't hear it at the same time. Everything was out of kilter. Coffee-break regulars straggled in separately. Children missed the school bus. People were late for appointments. Residents whose parents worked by the whistle for years were not reminded of their memories and felt badly.

Angry people mobilized against state government’s interference into none of its business. People demanded to know who exactly had complained to Springfield, if anyone actually did, in fact. And if they had, the complainers might want to consider relocating.

There were petitions, calls to legislators. Open defiance of the government was discussed, even in churches.

In short, the whistle war was the biggest stir in Canton since 1855, when 200 women hid axes under their shawls and marched downtown to destroy the Sebastopol Tavern.

I wrote a feature on the hubbub for my national newspaper. Other outlets followed. A Peoria TV station even had the news. The nosy villains from the state never knew what hit them. They had picked the wrong noise to mess with.

After too long a time, quiet word came that if the booming horn happened to resume seven times a day like it always had and never should have been silenced, there would be no trouble. So, it did. And there wasn't.

In appreciation, a local resident made a little wooden replica of the horn in his garage and sent it to me.

I still have it.

This is the 35th in an ongoing series of personal memories. Links to all the others are below.

More Neat People and a Nuclear Sub I've Met Along the Way

Malcolm's Memories: A Toddler's First Fourth

Malcolm's Memories: Train, Streetcars, and Grandma

The True Story of an Unusual Wolf, a Pioneer in the Wild

That Time I Wore $15K in Cash Into a War Zone

I Fell in Love With the South, Despite That One Scary Afternoon

More Memories: Neat People I've Met Along the Way

Unexpected Thanksgiving Memory, a Live Volcano, and a Moving Torch

The Horrors I Saw at the Three 9/11 Crash Sites Back Then

The Glorious Nights When I Had Paris All to Myself

Inside Political Conventions - at Least the Ones I Attended

Political Assassination Attempts I Have Known

The Story a Black Rock Told Me on a Montana Mountain

That Time I Sent a Message in a Bottle Across the Ocean...and Got a Reply!

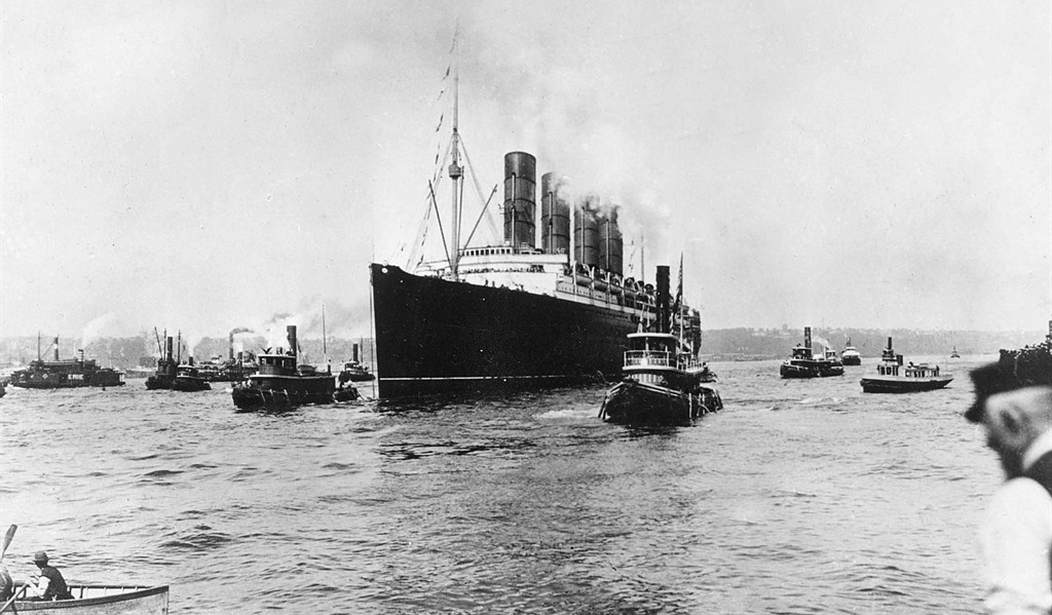

As the RMS Titanic Sank, a Father Told His Little Boy, 'See You Later.' But Then...

Things My Father Said: 'Here, It's Not Loaded'

The Terrifyingly Wonderful Day I Drove an Indy Car

When I Went on Henry Kissinger's Honeymoon

When Grandma Arrived for That Holiday Visit

Practicing Journalism the Old-Fashioned Way

When Hal Holbrook Took a Day to Tutor a Teen on Art

The Night I Met Saturn That Changed My Life

High School Was Hard for Me, Until That One Evening

When Dad Died, He left a Haunting Message That Reemerged Just Now

My Father's Sly Trick About Smoking That Saved My Life

His Name Was Edgar. Not Ed. Not Eddie. But Edgar.

My Encounters With Famous People and Someone Else

The July 4th I Saw More Fireworks Than Anyone Ever

How One Dad Taught His Little Boy the Alphabet Before TV - and What Happened Then

Muhammad Ali Was Naked When We Met

Editor’s Note: Do you enjoy RedState’s conservative reporting that takes on the radical left and woke media? Support our work so that we can continue to bring you the truth.

Join RedState VIP and use the promo code FIGHT to get 60% off your VIP membership!

Join the conversation as a VIP Member