Leadership changes in Russia and the old Soviet Union have been handled very carefully. Would-be successors want to be absolutely certain that the current incumbent is, shall we say, in no vertical position to resist a transition of power.

Meaning, he’s dead. Stone-cold dead. Because if the incumbent somehow recovers, everyone in the immediate area becomes stone-cold dead instead.

The question arises now because of reports, not yet officially confirmed, that Vladimir Putin, the 69-year-old former KGB agent who is frequently president or the power behind another president in recent years, has stomach cancer requiring surgery.

This would necessitate an anesthetic and thus, an acting president. But this is additionally complicated because, in February, the sick-looking leader launched an unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, claiming it was packed with Nazis and/or Americans and needed to become part of a restored Greater Russia.

And, of course, Putin’s security squad must also ensure the surgical team’s loyalty. Meaning if they like their families, they can keep their families. As long as they don’t screw up on Russia’s Big Guy.

The invasion of Ukraine, however, is not going well at all due to terrible logistics, lousy training, poorly-maintained equipment, inept military leadership, terrible discipline, and, not least, impressive Ukrainian spirit, imagination, and resolve, now enhanced by a flood of intelligence and heavy equipment from Europe and the U.S.

The savvy and military experience of our colleague streiff has put RedState ahead of the competition on the war with posts such as this and this one and this one.

Putin’s security forces have arrested hundreds of war protesters and critics and silenced most of the moneyed oligarchs, a number of whom have mysteriously turned up deceased recently, allegedly by their own hand.

These are the rich men behind Putin whose fortunes and nice boats are now threatened by tightening Western sanctions, restrictions, property seizures, and a disastrous war that could easily be ended if, say, Putin’s heart was to stop during surgery for unexplained reasons that could not be helped despite very valiant efforts by heroic doctors of Mother Russia.

Acting leaders in autocratic regimes have a way of becoming fond of their newfound powers and desire to make them more permanent. In another interesting way, any potential challengers and even critics have a way of turning up far away in a cold climate or worse.

So, how have these power transitions worked out historically for the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and now the Russian Federation?

Some American officials forever fuss over election results that turn them out of office. That doesn’t happen in Russia. The former leader is either in prison or the ground.

Russia had not one but two revolutions in 1917, one in March and the other in October. Overthrown was Czar Nicholas II, whose family had ruled that land for more than three centuries. To ensure that none of the royals returned to create trouble, his entire family, including all the children, were executed.

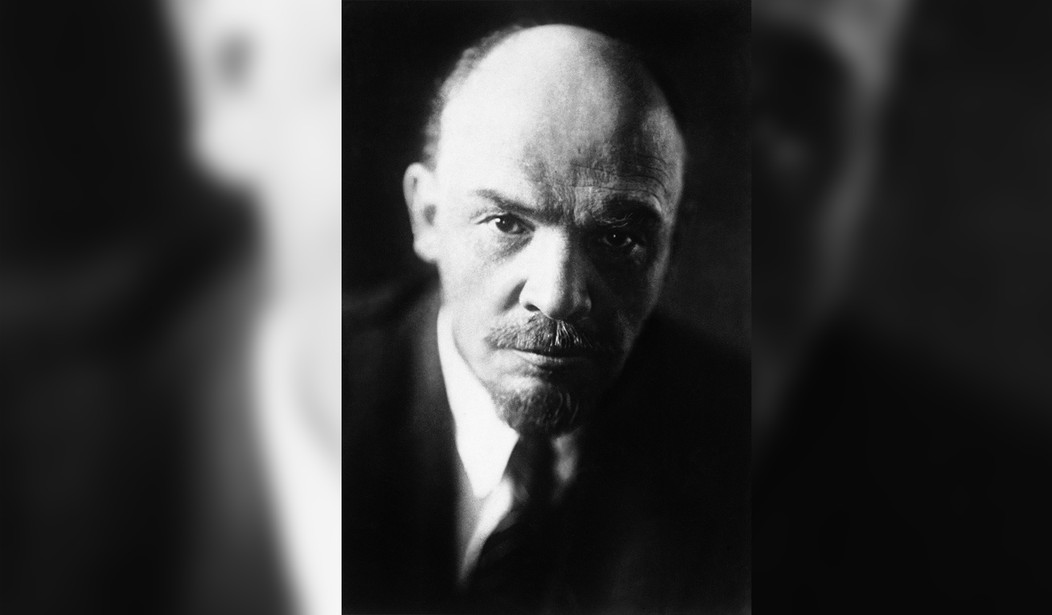

The first revolution produced an ineffective government largely of wealthy noblemen (an early word for oligarchs). That October, another revolution of peasants and workers erupted, organized by Bolsheviks led by another Vladimir, as in Lenin.

He’d been imprisoned as a communist in Germany. But the Kaiser put him on a train to Russia, hoping he’d foment turmoil that would get the Czar’s army out of World War I.

It worked.

In the early 1920s, however, Lenin began expressing concerns over Stalin amassing power. At the same time he began suffering from a series of paralyzing strokes. The whispers were from syphilis, but may also have been poison, a favored tool of the latter-day Vladimir, too. Lenin was hailed as a hero, of course, and got a grand four-day funeral organized by an aide and former bank robber, Josef Stalin.

Stalin authored a Lenin cult, which he used to control opponents. He squeezed out a Ukrainian native, Leon Trotsky, another revolutionary he perceived as a potential challenger though he was in distant exile. There, Trotsky later fell victim to an ice ax wielded by an assassin sent by Stalin.

Whatever is stronger than iron, Stalin ruled by that kind of fist. Countless millions of his countrymen died in his purges and collectivization famines, especially in Ukraine. In 1938, Stalin put some guy named Nikita Khrushchev in charge there.

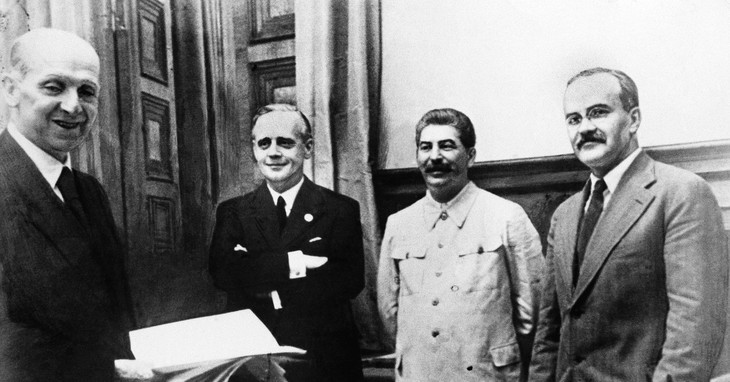

A year later, with World War II looming, Stalin signed a nonaggression treaty with Adolph Hitler. The Soviet leader thought that protected him and got him part of Poland, which Hitler invaded a few days later. An ever-suspicious Stalin then launched a thorough purge of his army’s officer corps.

Good thing the Stalin administration never had to face a reelection campaign. Because less than two years later Hitler turned on Stalin’s poorly-led army and, like Napoleon 129 years before, made large costly advances.

Never mind poor leadership and lack of training, Stalin just kept throwing thousands of troops at German forces. And if his troops faltered or fell back, Stalin’s orders had them shot by their own forces.

When Germans captured his son Jacob and offered an exchange, Stalin declined.

Thanks to immense military aid from the United States and Britain and poor decisions made by Hitler, (any of this sounding familiar yet?) Soviet forces eventually prevailed. And indeed, they advanced far enough to lower what Winston Churchill called an Iron Curtain over Eastern Europe.

Like President Franklin Roosevelt, Stalin’s health was deteriorating near the war’s end. He smoked heavily, had hardening of the arteries, a mild stroke in spring of 1945, and then a major heart attack that fall.

In March of 1953, the story goes, he had a massive stroke and fell into a coma. Suspicions grew over time, however, that his final stroke was helped along by some warfarin, a water-soluble rat poison.

Either way, Stalin ended up as dead as the millions who perished under him. And as often happens in autocratic regimes, successor competitors – the Khrushchev fellow and Georgi Malenkov — agreed to share leadership under the overall guidance of Lavrenti Beria, the ruthless head of Stalin’s secret police.

Beria, however, began spouting liberal ideas like freeing many of the 2.5 million political prisoners and loosening strictures on East Germany. Perhaps worst, he mocked fellow Politburo members.

Predictably, within a few months, they conspired against him. Held a fake trial. And Beria ultimately died from a sudden bullet hole in the forehead.

Khrushchev cemented his power as the first secretary of the party.

However, at a summit in Vienna, he misjudged John Kennedy as weak. That lead to the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, Khrushchev ultimately backing down, and his failed economic policies plus cantankerous mien resulted in his ouster in 1964. He was replaced by an ally Leonid Brezhnev.

Khrushchev died peacefully seven years later, according to his son, feeling satisfied that he’d been in the country’s first peaceful transition of power.

There have been others since, usually ending in poor health or resignation. Vladimir Putin’s rise was peaceful. He resigned from the KGB’s reserves in 1991, worked in Saint Petersburg’s city administration, then moved to Moscow in 1996, where President Boris Yeltsin named him head of the FSB, the KGB’s successor.

In 1999, Yeltsin named Putin to the Number Two job, prime minister, but then suddenly resigned and made Putin acting president.

Putin pardoned Yeltsin, like Gerald Ford and Richard Nixon, won his own election a few months later, and established a reputation for being a man of action — albeit ruthless action in Chechnya and that Moscow theater that terrorists took over with hostages.

Recognizing the growing economic power of Russia’s wealthy oligarchs, Putin reportedly did a deal with them. He vowed not to re-nationalize their industries and leave them to their riches if they stayed out of politics.

So far, so good in that area until now. Some are grumbling about the West’s sanctions and overall costs of Putin’s wanton — and so far unsuccessful — war in Ukraine.

The rest is unfolding history with, possibly, mortal health setting its own term limit.