Let me preface this up front by saying I am not a lawyer. I don’t play one on the internet. But I do have a degree in history and a deep love of American history.

Right now there is a masturbatory exercise underway in the US Senate. (Surprise, right?) The Senate Judiciary Committee is claiming to be hard at work drafting a law that will prevent President Trump from firing Robert Mueller. This is not only a dumb idea, it is unconstitutional on its face. It is dumb because there is no way in hell that this bill gets a veto-proof majority in the House and Senate. Because, let’s not fool ourselves, there is no way possible that President Trump signs into law a bill limiting his authority absent a veto-proof majority. It is also unconstitutional. How do we know that? Because the US Supreme Court has already ruled on the issue.

In 1865, Vice President Andrew Johnson succeeded to the presidency upon the assassination of President Lincoln. It would have been hard to find a man more unsuited for the job of overseeing the healing of the wounds of the Civil War, and the enforcement of the Reconstruction amendments, than Johnson. He was a southerner but his critical flaw was that he was petit bourgeois who idolized the planter aristocracy. If wasn’t long before he was locked in battle with the “Radical Republicans” who were pushing for a much harsher regime of Reconstruction than Johnson wanted to impose.

The key individual in what happened next was the Lincoln-appointed Secretary of War, Edwin Stanton. Stanton was a brilliant man but had two flaws, two major ones, I should say. He was damned near impossible to work with and he was a Radical Republican with a lot of friends on Capitol Hill. Stanton had made it known that he would not resign, something Johnson had expected him to do to allow Johnson to name his own Secretary of War, and that as far as Reconstruction was concerned, he was firmly allied with Congress and opposed to Johnson.

Congress had thought Stanton might be forced out and to forestall this they passed the “Tenure of Office Act” in March 1867 and they did so over Johnson’s veto.

The Tenure of Office Act was pretty simple. It said the president could only remove any executive branch officer who had been appointed by the president with the advice and consent of the Senate if Congress was in session and the Senate consented to the removal. This, obviously, flies in the face of Article II of the Constitution which is silent on dismissal of “inferior officers.” Not because the Founders hadn’t thought about it, but because it was agreed at the Constitutional Convention that the power to fire officers of the Executive Branch was implicit in the power to appoint them.

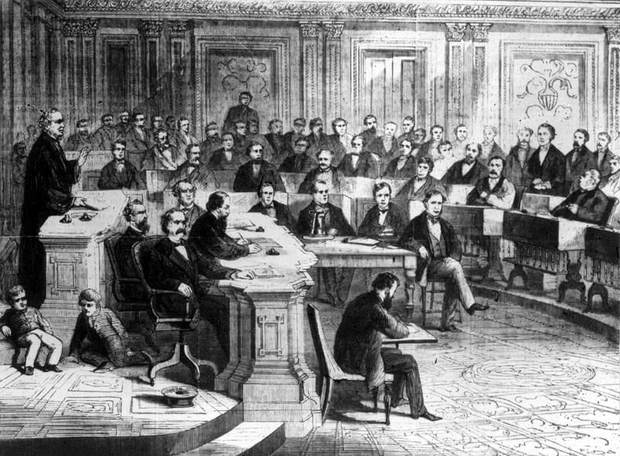

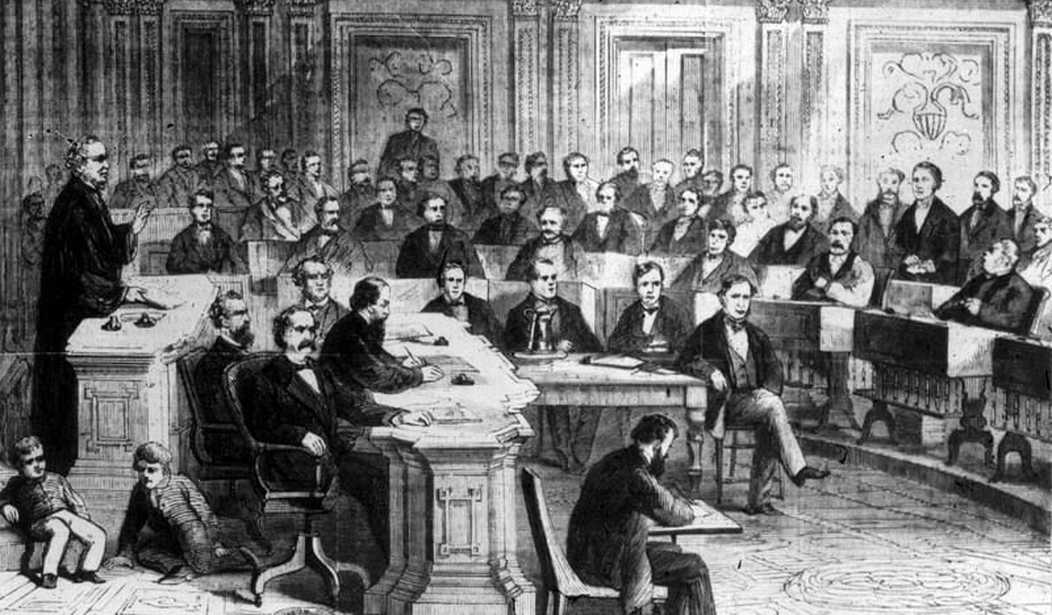

Andrew Johnson eventually had enough of Stanton and fired him in August 1867. Congress moved to impeach Johnson based on him being a dick and violating the Tenure of Office Act, but mostly for him being a dick. He survived, as we know, by one vote.

This law stayed on the books until it was eventually repealed in 1887.

Fast forward to 1920. A guy named Frank S. Meyers was serving as postmaster in Portland, OR. He was a local Democrat politico who had first been appointed postmaster in 1913 and was now in his second appointment. Each appointment had been subject to the advise and consent power of the Senate (as an aside, the Senate still does this kind on thing. I have a copy of the Congressional Record where the US Senate took up the matter of my nomination to be a second lieutenant in the US Army–along with a couple of thousand others–and, against their better judgment, voted to confirm me to that august position). Myers had a confrontational personality, he got involved in some very ugly public spats with a member of Congress as well as prominent Oregon Democrats. The post office became Ground Zero of political intrigue. In January 1920, he was told by Woodrow Wilson to pack his stuff and get off the battlefield. Unsurprisingly, Myers sued.

Myers contended that his firing was illegal because an 1876 law provided that, “Postmasters of the first, second and third classes shall be appointed and may be removed by the President by and with the advice and consent of the Senate and shall hold their offices for four years unless sooner removed or suspended according to law.” Wilson hadn’t asked the Senate for permission and therefore he was not properly fired. The case made its way to the US Supreme Court where it is enshrined as Myers vs. United States. Chief Justice William Howard Taft wrote the decision for the six justice majority.

First. Mr. Madison insisted that Article II by vesting the executive power in the President was intended to grant to him the power of appointment and removal of executive officers except as thereafter expressly provided in that Article. He pointed out that one of the chief 116*116 purposes of the Convention was to separate the legislative from the executive functions. He said:

“If there is a principle in our Constitution, indeed in any free Constitution, more sacred than another, it is that which separates the Legislative, Executive and Judicial powers. If there is any point in which the separation of the Legislative and Executive powers ought to be maintained with great caution, it is that which relates to officers and offices.” 1 Annals of Congress,

…

The power to prevent the removal of an officer who has served under the President is different from the authority to consent to or reject his appointment. When a nomination is made, it may be presumed that the Senate is, or may become, as well advised as to the fitness of the nominee as the President, but in the nature of things the defects in ability or intelligence or loyalty in the administration of the laws of one who has served as an officer under the President, are facts as to which the President, or his trusted subordinates, must be better informed than the Senate, and the power to remove him may, therefore, be regarded as confined, for very sound and practical reasons, to the governmental authority which has administrative control. The power of removal is incident to the power of appointment, not to the power of advising and consenting to appointment, and when the grant of the executive power is enforced by the express mandate to take care that the laws be faithfully executed, it emphasizes the necessity for including within the executive power as conferred the exclusive power of removal.

There are lots of practical reasons why Trump should not change the locks on Mueller’s office, though I must admit that day by day I see fewer of those reasons making much sense, but there is no legal reason President Trump cannot fire, or direct the firing of, Mueller. (I think the idea that Mueller being appointed by a deputy cabinet secretary gives him immunity from the president firing him is utterly ridiculous. Trump appointed Rosenstein so it makes sense that the can fire anyone Rosenstein appoints, otherwise the ability to actually supervise Rosenstein is restricted, not by law but by departmental fiat. But I’m not going to argue with people who believe that is the case.) There is no way that the Congress can pass a law to protect Mueller because to do so requires Trump to go along with it (or override his veto). Then it requires Trump to abide by that law. And finally, it relies upon the US Supreme Court to toss out a fairly significant precedent that is nearly 100 years old. The odds of this court majority saying James Madison was a dunce approach zero.

In an FDR-era Supreme Court case, the court held that the firing of an officer within the executive branch was at the discretion of the president but Congress could place limits on that power when it came to removing members of independent agencies. The case upholding the original special counsel law found that because the law placed firing of the special counsel in the hands of the attorney general that was licit because the attorney general was appointed by the president and, therefore, the ability of the president to fire was not impeded. Both those decisions relied upon Myers. The fly in the ointment is Morrison vs. Olson where the Supreme Court did uphold the Watergate independent counsel law which did require consultation with a small number of Senators before firing was allowed. That law expired in 1999. this is how the late Justice Antonin Scalia described it:

Probably the most wrenching was Morrison v. Olson, which involved the independent counsel. To take away the power to prosecute from the president and give it to somebody who’s not under his control is a terrible erosion of presidential power. And it was wrenching not only because it came out wrong—I was the sole dissenter—but because the opinion was written by Rehnquist, who had been head of the Office of Legal Counsel, before me, and who I thought would realize the importance of that power of the president to prosecute. And he not only wrote the opinion; he wrote it in a manner that was more extreme than I think Bill Brennan would have written it. That was wrenching.

Raise your hand if you think what I just laid out to you isn’t known by the Senate Judiciary Committee. See, I didn’t think so.

What Grassley is doing is laying down a marker. He’s sending a message that he really doesn’t want to deal with the crap-storm that firing Mueller will create. A month ago, I would have said Trump will pay attention. After Monday, I’m not so sure.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member