Photo credit: AFL-CIO via Flickr Creative Commons https://www.flickr.com/photos/labor2008/

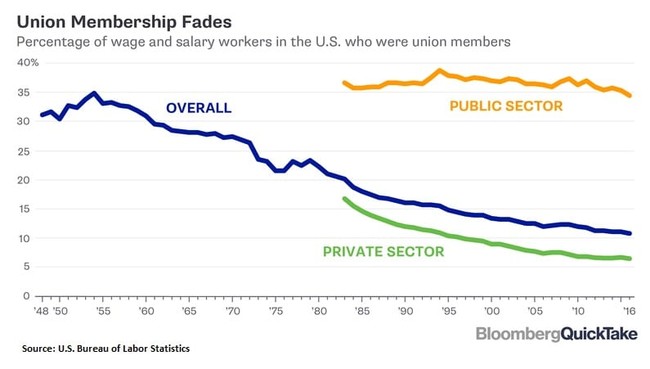

As the participation in American workers in labor unions has plummeted for a variety of reasons, the sole bright spot for organized labor has been in the public sector where teachers, firefighters, and police officers are routinely part of bargaining units.

These unions are sustained, in some cases, by closed-shop laws that require union membership as the price of employment or the payment of an “agency fee” to the union to cover contract negotiations and grievance representation if you don’t want to be a full member. This requirement, that non-members still had to pay an agency fee, comes from the 1977 Supreme Court decision, Abood vs. Detroit Board of Education.

Over the years, this decision has been chipped at around the edges until it has become very obvious that forced subsidization of union negotiations by non-members runs afoul of the First Amendment decisions by the Supreme Court. Abood seemed headed for the ash heap of history in 2016 in a case that made its way to the Supreme Court called Friedrichs vs. California Teachers Association. The unions were only saved by the untimely death of Justice Antonin Scalia and a 4-4 tie which preserved a 9th Circuit decision affirming the requirement to pay an agency fee.

Now another case slated for this term is probably going to drive the last nail in the coffin containing compulsory fees for non-union employees. The case comes out of Illinois and pits a state employee against the Democrat cash cow, AFSCME:

Mark Janus is a child support specialist employed by the Illinois Department of Healthcare and Family Services. He has declined membership in the union, as is his constitutional right, but under the Illinois Public Labor Relations Act he’s still is required to pay the union an “agency fee” as a condition of keeping his job. That fee is supposed to cover his share of the union’s expenses outside of politics – 84 percent of the full member dues last year (by the union’s calculation).

His argument is that all public union spending is so entwined with politics that he should not be compelled to subsidize any of it.

Writing this commentary piece in the Chicago Tribune, Janus said, “To keep my job at the state, I have to pay monthly fees to the AFSCME, a public union that claims to ‘represent’ me. The union is not my voice. The union’s fight is not my fight.”

This is how SCOTUSblog describes the case called Janus v. American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, Council 31.

The highest-profile grant came in Janus v. American Federation of State, Municipal and County Employees, a challenge to the fees paid by public-sector employees who are not members of the union that represents them. The justices have already considered the question presented by the case twice without resolving it, but are almost certain to do so during this go-round – with potentially serious implications for the union.

When the justices review the case of Mark Janus, an Illinois state employee, they will not necessarily be writing on a blank slate. In 1977, in Abood v. Detroit Board of Education, the Supreme Court ruled that, even if they cannot be required to pay fees that a union would use for political activity, like union organizing, public-sector employees can be required to pay a fee to cover the costs of contract negotiations. But Janus argued that even requiring him to pay the more limited fee violates his First Amendment rights because issues related to contract negotiations – like salaries, pensions and benefits for government employees – are inherently political. Therefore, he contends, his fee is going to support speech that is intended to affect the government’s policies, even if he disagrees with it. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 7th Circuit rejected Janus’ argument, holding that it lacked the power to overrule the Supreme Court’s decision in Abood. But, Janus told the justices in his petition for review, they do have that power and should exercise it here.

The justices did not reach the union-fees issue the first time they considered it, in the 2014 case Harris v. Quinn; instead, they ruled that the employees in that case – home-health-care workers who were paid by the state – were not “true” public employees. They returned to the question again two terms ago and heard oral argument in January 2016, but they deadlocked after the February 13, 2016, death of Justice Antonin Scalia. With Justice Neil Gorsuch now on the bench, the justices are expected to decide the issue once and for all.

Smart money says Abood is overturned. Not only because of Neil Gorsuch on the bench but because the Trump Justice Department has reversed the position taken by the Obama Justice Department in the Friedrichs case and endorsed Mr. Janus’s position:

The Office of Solicitor General had not previously weighed in on Janus, but under President Barack Obama it sided with unions in a nearly identical case, Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association, and argued that public-employee fair share fees were legal. That case (also financed by the Bradley Foundation) ended in a 4-4 deadlock in 2016 after the death of Justice Antonin Scalia, who had been expected to vote against fair share fees. It’s thought likely that with Justice Neil Gorsuch on the bench, the high court will abolish fair share fees later this term when it rules in Janus.

For the Trump administration, the court brief is the latest in a series of moves to roll back union power, including Trump’s appointment of pro-management board members to the National Labor Relations Board. In June, the Office of Solicitor General switched sides in another case before the high court concerning the legality of mandatory arbitration fees in employment contracts, which unions typically oppose. Under Obama, the Office of Solicitor General had argued that the fees were illegal, but under Trump it reversed field and declared them legal.

In its Janus brief, the Office of Solicitor General embraced the plaintiff’s argument that fair share fees violated his right to free speech. “In the public sector,” the brief said, “speech in collective bargaining is necessarily speech about public issues,” and “virtually every matter at stake in a public-sector labor agreement affects the public.”

“Compelling employees to subsidize speech on politics and public policy imposes a severe burden that even highly restrictive prohibitions on speech in the workplace do not,” the brief said.

If the Supreme Court does, in fact, put down Abood like the crippled old dog that it is, this will mark a sea change in the way politics are conducted in most of the country. Without access to “agency fees,” state and municipal unions will begin to feel the pinch. The money they have for full-time staff and lobbyists and “gifts” to politicians will dwindle and without money to throw around they cease to be a political force.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member