Sad to say, we are living in a post-Christian society. As a nation, 70+% may claim to be Christian but the facts show something very different. Last year, an extensive survey by the Barna Group, a non-profit that tracks religious practice in America, found that of the 72% of self-proclaimed Christians in America, only 56% believe Christ is God. This calls into question exactly what the other 44% believe. Less than a third, a mere 31%, believed Christ to be without sin. In essence, a super-majority of self-avowed Christians don’t even believe the basics of their faith. Which simply goes to show that claiming to be something doesn’t make it true.

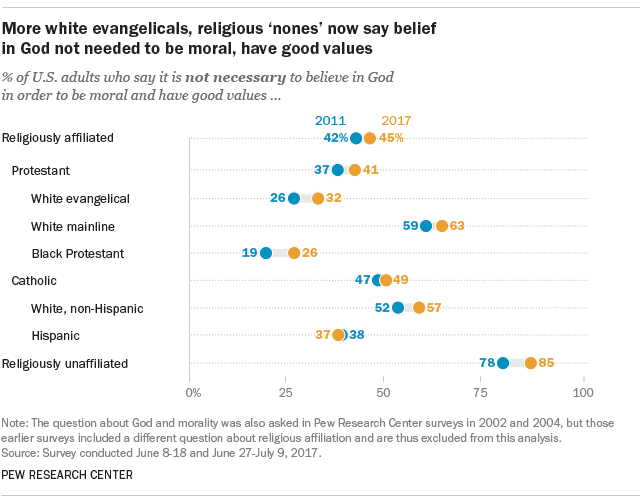

So I was less than surprised by this poll conducted by the Pew Research Center.

This is the kind of finding you’d expect from a society that will proclaim “I’m not religious but I’ve very spiritual.” The problem with it is the same with the first poll I cited in which people have a totally wrongheaded understanding of Christ. It simply is not true.

The underlying fallacy is that without an understanding of an absolute right and wrong, good and evil, all decisions can be moral and good because we, then, define the morality and goodness of our actions and damned few will condemn themselves as an immoral reprobate by their own standards. And without an absolute and immutable standard for moral and immoral, we are free to change that standard according to the circumstances. For instance, this essay by an atheist group disavows natural law and in its place looks to some sort of logic as a guide:

Justice has its roots in the problem of determining fairness and reciprocity in cooperation. If I cooperate with you in tilling your field of corn, how much of the corn is due me at harvest time? When there is justice, cooperation operates at maximal efficiency, and the fruits of cooperation become ever more desirable. Thus, enlightened self-interest entails a desire for justice. With justice and with cooperation, we can have symphonies. Without it, we haven’t even a song.

Let us bring this essay back to the point of our departure. Because we have the nervous systems of social animals, we are generally happier in the company of our fellow creatures than alone. Because we are emotionally suggestible, as we practice enlightened self-interest we usually will be wise to choose behaviors which will make others happy and willing to cooperate and accept us – for their happiness will reflect back upon us and intensify our own happiness. On the other hand, actions which harm others and make them unhappy – even if they do not trigger overt retaliation which decreases our happiness – will create an emotional milieu which, because of our suggestibility, will make us less happy.

…

The task of moral education, then, is not to inculcate by rote great lists of do’s and don’ts, but rather to help people to predict the consequences of actions being considered. What are the long-term as well as immediate rewards and draw-backs of the acts? Will an act increase or decrease one’s chances of experiencing the hedonic triad of love, beauty, and creativity?Thus it happens, when the Atheist approaches the problem of finding natural grounds for human morals and establishing a nonsuperstitious basis for behavior, that it appears as though nature has already solved the problem to a great extent. Indeed, it appears as though the problem of establishing a natural, humanistic basis for ethical behavior is not much of a problem at all. It is in our natures to desire love, to seek beauty, and to thrill at the act of creation. The labyrinthine complexity we see when we examine traditional moral codes does not arise of necessity: it is largely the result of vain attempts to accommodate human needs and nature to the whimsical totems and taboos of the demons and deities who emerged with us from our cave-dwellings at the end of the Paleolithic Era – and have haunted our houses ever since.

But this is hokum.

Let’s use the thought process encouraged here: “The task of moral education, then, is not to inculcate by rote great lists of do’s and don’ts, but rather to help people to predict the consequences of actions being considered. What are the long-term as well as immediate rewards and drawbacks of the acts?”

You are at a bus station and there is a blind woman sitting alone. There is no one around. Do you take her purse? There are no downsides to your act. There are no witnesses and she can’t harm you. There is an immediate reward: the proceeds of her wallet. You’ll probably never encounter her again, If you do, she can’t recognize you. What possible cooperative strategy could be used to justify not robbing her? I don’t think there is one.

Fairness and justice and cooperation only exist when the strong voluntarily submit to the demands of the weaker. What tells us that “the hedonic triad” has value and that we improve our lives by striving for it? Nothing other than ourselves. And why does “love, beauty, and creativity” hold a higher place than “having sex whenever I want and taking all of your stuff if I want it?” Does “enlightened self-interest” have any meaning if we, ourselves, are the judges of that enlightenment or if it is based on what we can get away with?

First we must distinguish between “enlightened” and “unenlightened” self-interest. Let’s take an extreme example for illustration. Suppose you lived a totally selfish life of immediate gratification of every desire. Suppose that whenever someone else had something you wanted, you took it for yourself.

It wouldn’t be long at all before everyone would be up in arms against you, and you would have to spend all your waking hours fending off reprisals. Depending upon how outrageous your activity had been, you might very well lose your life in an orgy of neighborly revenge. The life of total but unenlightened self-interest might be exciting and pleasant as long as it lasts – but it is not likely to last long.

The person who practices “enlightened” self-interest, by contrast, is the person whose behavioral strategy simultaneously maximizes both the intensity and duration of personal gratification. An enlightened strategy will be one which, when practiced over a long span of time, will generate ever greater amounts and varieties of pleasures and satisfactions.

This sounds rather like a robber baron and a handful of heavily armed henchmen running riot over the countryside to me.

In fact, when one looks at nature one doesn’t find this to be very much in evidence. The runt of the litter is shunted aside by his siblings to starve. A male animal will kill nursing young in order to bring the female into heat again. A group kill is not shared evenly, the biggest, most powerful eats its fill…frequently the animals who make the kill are driven off by more powerful beasts who were not in on the hunt or kill. The old and infirm are not cared for, they are left to their own devices. In pagan societies, and in neo-pagan ones if we look at Europe, we see the same behaviors.

No one doubts that there are atheists who live very fine and moral lives when judged by Judeo-Christian precepts. Doing so is merely an optional choice on their part and one that is not binding in the long run. Saying that, however, is not the same as saying that atheism can provide the precepts for a fine and moral life. It can’t because its morality is subjective and malleable.

Without God, there is no true morality. At best you have a social contract that is utilitarian and consequentialist in nature. Where we are without intrinsic value as humans we are only worth what we can directly contribute to society with its concomitant cruelty to the weak and infirm. There is good reason why even atheists think other atheists are amoral and untrustworthy.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member