The Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (CFPB), which has become overtly activist and routinely oversteps its authority under the chair Rohit Chopra and the Biden administration, is preparing to ignore the law once again.

As you might recall, the bureau receives its funding from the Federal Reserve, insulating it from the appropriations process and making it difficult for Congress to provide meaningful oversight. That was by design:

Rohit Chopra, Biden’s CFPB Director, is a Elizabeth Warren protégé who has an ambitious agenda and has been working behind the scenes to massively expand the regulatory state. When Warren and her allies set up the bureau, they deliberately set it up with this funding mechanism to insulate it from oversight, and Chopra’s the director she’s been waiting for since the beginning, to shepherd her radical, socialist overhaul of the country’s financial services industry — and they have a very broad view of what should be considered part of the financial services industry. Chopra and Warren also have a broad view of the width of the CFPB’s “lane.”

Chopra's doing a bang-up job at shepherding Warren's radical agenda at CFPB so far, especially in areas where it has no authority, such as attempting to regulate and enforce competition/antitrust matters, attempting to "supervise" the process of student loan borrowers resuming payments after COVID pauses, and attempting to institute even more burdensome regulations on credit card and payday loan companies.

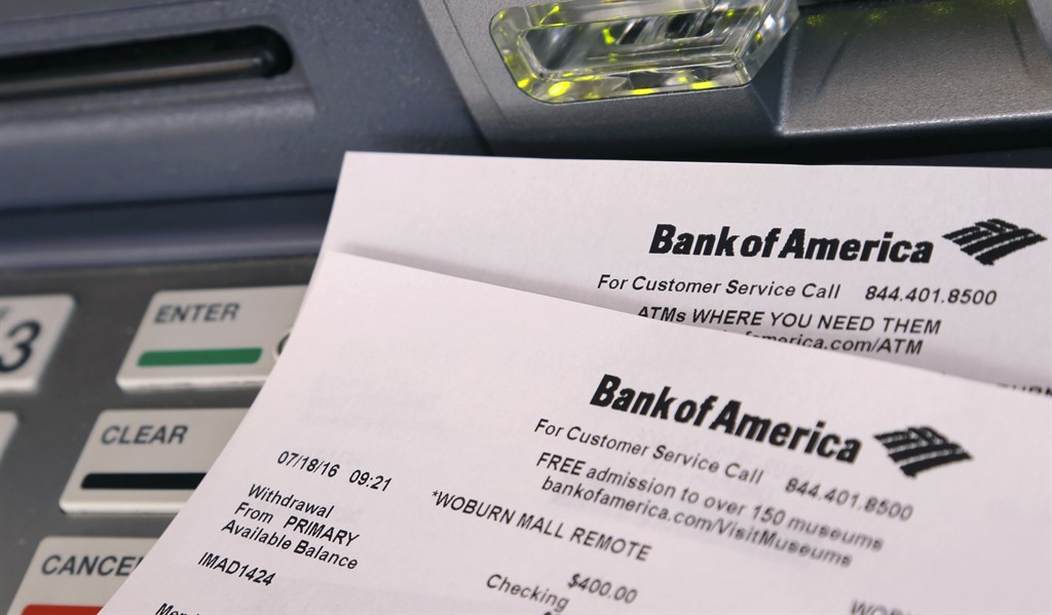

And now he and CFPB are attempting to redefine discretionary bank overdraft protection programs as "overdraft credit" extended by banks to customers and redefine the associated fees as "finance charges" so the agency can regulate them. Under the proposed rule, CFPB seeks to cap the fees at much lower rates than the current $35 industry standard for big banks.

Overdraft fees are exempted from the Federal Reserve Board's Regulation Z (implementing the Truth in Lending Act), and the Act doesn't specifically include overdraft programs, so the CFPB has to get creative if they want to sink their teeth into the fees.

Banks are pushing back, though, saying that if these discretionary overdraft programs are truly loans, then CFPB is attempting to set the interest rates for those loans - something they're not allowed to do by law:

The rule would let banks treat the overdraft as a loan to customers that charges interest. But the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act, which created the CFPB, bars the agency from setting interest rates. Banks say the caps on such fees, ranging from $3 to $14, therefore amount to an illegal limit on interest.

Banks could go above the cap only as a “breakeven,” if they show their costs for giving people overdraft protection exceeds the capped amount.

“By imposing additional—and onerous—requirements on overdrafts priced above the breakeven or benchmark fee, the Proposal impermissibly establishes a usury limit,” the American Bankers Association said in a comment letter to the agency.

The Bank Policy Institute argued in a letter to the CFPB that the bureau is "inappropriately attempting to subject overdraft to provisions in the 2009 Credit Card Accountability Responsibility and Disclosure (CARD) Act, such as limiting fees for accounts linked to a debit card," and says that both the Truth in Lending Act and the Credit CARD Act protections are different from overdraft programs because overdraft programs are discretionary:

A bank providing discretionary overdraft products has no legal obligation to cover overdrafts and, when it chooses to do so, may demand payment from the depositor at any time for the costs it incurred.

But former Rep. Carolyn Maloney (D-NY), one of the authors of the Credit CARD Act, says that regulation of overdraft programs fits within the Act's purposes:

At the time that Congress was considering the Credit CARD Act, it was already well established that overdraft credit is credit and that the credit card protections of TILA can apply to different forms of devices that access credit beyond traditional credit cards. In enacting TILA in 1968 and in passing the Credit CARD Act amendments, Congress intended the Act to be construed liberally to protect consumers.

It's well-known that some large banks engage in predatory overdraft practices designed to gouge customers, but competitive pressures are already having an effect on that practice. Credit unions are increasingly popular and for the most part have much lower overdraft fees than the large banks. A few large banks, such as Citigroup and Capital One, have stopped charging overdraft fees, and many banks have "next day grace" or low balance alert programs designed to help customers avoid overdraft fees in the first place. So even if the CFPB is eventually deemed to have authority to regulate these programs, it's unnecessary since the market is taking care of it.

A side note: a better way for the CFPB to protect consumers and limit their exposure to overdraft fees is to require businesses to provide a way for their customers to cancel services and subscriptions using the same method they signed up for them in the first place. Meaning, if someone signs up for a streaming service or cable or satellite radio online, they shouldn't have to make a phone call to cancel that service. They should be able to cancel it online. And, they could require that businesses that offer monthly or yearly subscriptions allow customers to sign up for a reminder service where they can opt out of ongoing charges - online - a few days before the scheduled renewal.

It all might be irrelevant anyway, since the Supreme Court is set to rule on a case that could "topple the CFPB's funding mechanism." Back in October 2022 a three-judge panel in the Fifth Circuit ruled that CFPB's funding mechanism violated the Constitution's doctrine of separation of powers, and that case is now before SCOTUS.

The stakes in the case are high: If the Supreme Court upholds the Fifth Circuit’s ruling could topple the CFPB’s funding mechanism and stymie its ability to carry out its mission in the future. It could also, potentially, throw 12 years of the agency’s past actions and regulations into question. And such a decision could draw additional legal challenges against other agencies that are similarly funded.

Oral arguments were heard in October 2023, and a ruling is expected this spring.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member