We know that the progressive left engages in Astroturfing. What many are just realizing or admitting is that what you see on the surface when an issue suddenly becomes hot is just that, surface. There are years of effort behind what you see, and it’s not just in organization. Astroturfing even consists of creating the scientific and legal “research” pointing to the desired conclusion. We know that the oil and tobacco industries did this decades ago, but the practice wasn’t limited to that time and those industries. More recently, we’ve seen this happen with regard to gun control (Everytown and Bloomberg-funded “research), criminal justice (Soros-affiliated groups and think tanks fund research that is then used by District Attorney candidates to claim the “science” backs their “reimagining” efforts), and, of course, Critical Race Theory.

Now a massive astroturfing effort is happening in the field of copyright law, and anyone who produces creative content should be paying close attention. As I wrote last week, there are major problems with the American Law Institute’s Restatement project, starting with how the project was initiated (at the request of a Google-funded, anti-copyright law activist professor) and the Lead Reporter’s unacknowledged conflicts of interest. Major flaws in the draft Restatement have been pointed out by other prominent copyright law scholars, a bipartisan group from Congress, the Register of Copyrights (the director of the Copyright Office), and even Advisors to the project. All of these groups essentially claim that the Restatement incorrectly interprets the Copyright Act and the policy preferences of the Reporters are improperly included. A letter to ALI from 10 of the project’s advisors states:

The Draft has a variety of problems including inaccurately summarizing the text of the Copyright Act, confusing explanations of important principles and misleading illustrations. Moreover, as further detailed below, these problems uniformly reflect an unduly restrictive view of copyright law that is not consistent with the robust statutory rights granted by Congress to authors.

Is the problem that the Restatement draft is flawed, or is it that “progressive” forces and their capitalist enablers, such as Google and Spotify, are using the Restatement to create a new legal “gold standard” that their attorneys can use in court to get favorable rulings and set new precedent in the arena – effectively changing the law through judicial activism and not through the legislative branch?

When examining the backgrounds, prior statements on copyright issues, and money connections of the Lead Reporter, NYU law professor Christopher Sprigman, his Associate Reporters, and Advisor Pamela Samuelson, the it’s easy to conclude that changing the law through ALI’s Restatement is exactly what they intend to do.

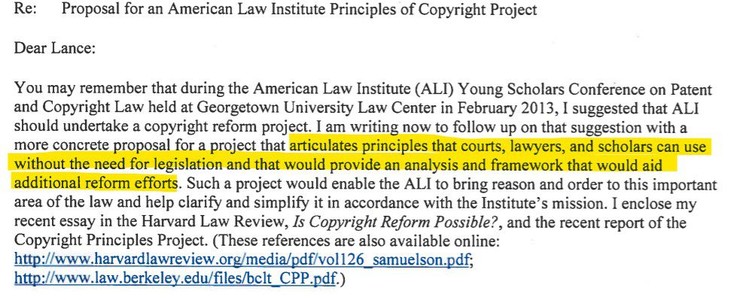

Samuelson, who instigated the project, made her goal clear to ALI as early as February 2013. On September 13, 2013, Samuelson wrote to ALI with a “more concrete proposal” after verbally proposing a copyright Restatement at a February conference, laying out precisely what she wanted to do – “articulate principles that courts, lawyers and scholars can use without the need for legislation” and “provide an analysis and framework that would aid additional reform efforts.”

Sprigman’s intent was also clear to the ALI from the start. In a September 2014 proposal memo to Richard Revesz, ALI’s Director, Sprigman listed a number of areas in copyright law he believed would soon end up in the appellate courts, then stated (emphasis added):

These are questions that courts will be obliged to answer in the coming years, and carefully-reasoned guidance from a Restatement of Copyright Law is bound to have a substantial role in shaping the law.

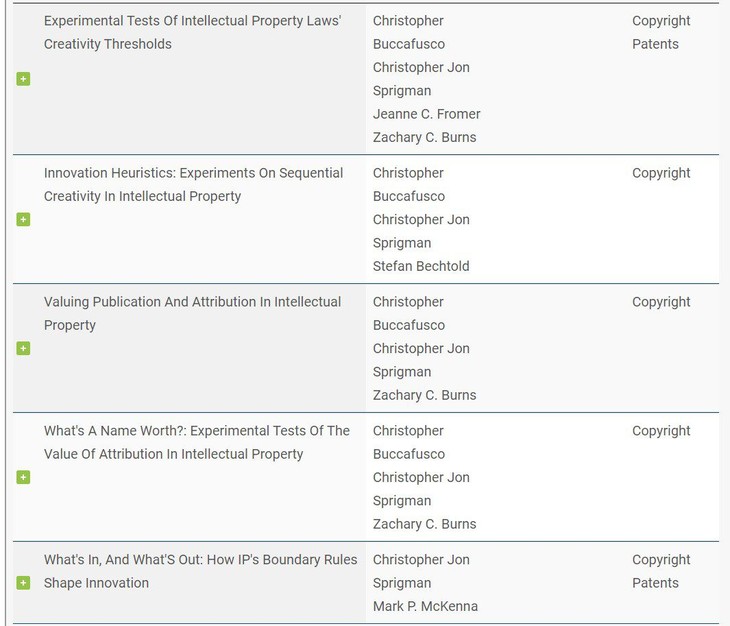

An examination of the Associate Reporters, who were nominated by Sprigman to participate in the project, shows that they also have undisclosed conflicts of interest and are hardly neutral legal scholars on the topic.

Given Sprigman’s pervasive conflicts of interest and known extremist views against copyright laws, it’s stunning that ALI thought he’d be a great candidate to lead the Restatement.

To start with, Google has funded five of Sprigman’s research projects since 2011. While the awards had already been made when Sprigman started working as the Lead Reporter on the Restatement, three of them were published after the project started.

In addition, Sprigman has represented Spotify in major court cases in which he argued that since Spotify was simply streaming songs and not reproducing and distributing them, they didn’t owe mechanical royalties to the publishers and songwriters. In the Bluewater v. Spotify case, he argued:

“Plaintiff alleges that Spotify “reproduce[s]” and “distribute[s]” Plaintiff’s works, thereby facilely checking the boxes to plead an infringement of the reproduction and distribution rights. But Plaintiff leaves Spotify guessing as to what activity Plaintiff actually believes entails “reproduction” or “distribution.”

The only activity of Spotify’s that Plaintiff identifies as infringing is its “streaming” of sound recordings embodying Plaintiff’s copyrighted musical compositions.

But “streaming” – by its very definition – cannot infringe upon either the reproduction right under 17 U.S.C. § 106(1) or the distribution right under 17 U.S.C. § 106(3).

In Sprigman’s view, the purpose of US copyright law to “promote the progress of science and useful arts” is best fulfilled by nearly eliminating copyright protections because collaboration and creativity occur more frequently when everyone has access to someone else’s work. It’s evidently lost on him that creatives might need to be compensated for their work, and without any copyright protection they wouldn’t have any incentive to create. Who in their right mind would write a book knowing that some tech company could nearly immediately publish an online version – without paying the author for the rights – because they think everyone in the world should be able to read that book?

Sprigman’s “research” bears out his opinions, of course, and those opinions were very well-known before ALI greenlighted the Copyright Restatement project and named Sprigman to lead it. Way back in 2006 Sprigman testified before the House Judiciary Committee regarding intellectual property rights, and then-Rep. Bob Goodlatte commented:

Mr. Sprigman . . . you have along record of opposing measures passed by the Congress that have originated in this committee.

It would seem that Sprigman has a long history of not liking the manner in which we traditionally pass or amend laws in this country.

He also wrote a book in 2012, “The Knockoff Economy,” which extols the virtues of knockoffs and claims that when there are no “restrictions on copying…creativity remains surprisingly vibrant,” and that “in some [industries] copying actually spurs innovation.”

Of course, in his mind copyright is an unfair barrier to entry. In a Houston Law Review article, Sprigman wrote:

Copyright is a tax on learning. It is a tax on culture. It is a tax on speech. And this tax is more than an inconvenience. It is a barrier to those who cannot, or will not, pay it.

And to those in the music industry who wouldn’t get mechanical royalties from streaming services if Sprigman had his way, he has even more to say, via The Knockoff Economy Blog:

Cut off the illegal downloads, and you cut off a potentially significant source of promotion.

In his mind, copying isn’t theft, anyway. Writing at the Freakonomics blog in April 2012, Sprigman said:

“[W]hen Hollywood or the U.S. government says that music or movie downloaders are ‘pirates’ or ‘thieves,’ they are indulging in a bit of loose rhetoric. There are, in general, good moral reasons not to take what doesn’t belong to you. But…copying is not theft.”

And if an “irrational” content creator doesn’t want to give permission for someone to use their copyrighted work, Sprigman believes the courts should be able to declare it fair use anyway. From a University of Chicago Law Review article he penned in 2011:

If authors and owners of copyrighted works make irrational demands that prevent the licensing of their work, then secondary works with surplus social value may not get made. . . . if a court could reliably detect the presence of significant creativity and endowment effects, it might consider declaring the secondary use fair and thus not infringing.

How could a court “reliably detect the presence of significant creativity and endowment effects”? Undoubtedly, that kind of guidance would be provided in the Restatement. (Yes, that’s sarcasm.)

Sprigman’s views are shared by the four Associate Reporters: Daniel Gervais, Lydia Pallas Loren, Molly Shaffer Van Houweling, and R. Anthony Reese.

In 2010 Gervais postulated that piracy was “a new form of social interaction,” and then in 2017, after the Restatement was well underway, argued in the Nashville Post that if we just give users “access to music, films, books, etc., wherever and whenever they want,” we will “limit unpaid unfair uses.” He graciously allowed that “proper financial flows for commercially significant uses” would have to be ensured, but again, who defines “commercially significant”?

Like Sprigman, Gervais has direct ties to Google.

Gervais played a role in a prominent copyright lawsuit against Google, where publishers claimed that the posting of book excerpts online should be forbidden because of copyright issues. The ultimate solution would be allowing all books….to be available on the internet, Gervais said.

Van Houweling too believes that copyright just isn’t fair and claims that it “endangers [people’s] expressive opportunities.”

Copyright now needs to come to terms with the ways in which it may endanger the expressive opportunities of those who cannot afford to pay for permission to build upon copyrighted works.

Coincidentally, around the time the Restatement was getting started Van Houweling founded the requisite astroturf “advocacy group,” whose members would undoubtedly churn out letters and “research” favorable to Google’s interests.

The soon-to-emerge Authors Alliance, a copyright revamp advocacy group, provoked skepticism and condemnation from authors’ rights groups, including the Authors Guild… ‘If any of you earn a living as a writer, or hope to, I strongly urge you not to join’ the alliance, said [Board Member T.J. Stiles], calling the alliance an ‘astroturf organization.’

Associate Reporter and Boston University law professor Lydia Pallas Loren believes that copyright law is misunderstood by many. In a 1999 piece in Open Spaces Quarterly, Loren wrote:

The misunderstanding held by many who believe that the primary purpose of copyright law is to protect authors against those who would pilfer the author’s work threatens to upset the delicate equilibrium in copyright law….This dark side, this pervasive misconception, is turning copyright into what our founding fathers tried to guard against –a tool for censorship and monopolistic oppression.

Loren is apparently not a fan of the Music Modernization Act, and in December 2019 made that known in a Boston University Law Review piece entitled, “Copyright Jumps the Shark: The Music Modernization Act.”

And Associate Reporter R. Anthony Reese believes that shutting down illegal file sharing sites is “bad for society.”

There are many, many more examples of the Reporters’ bias and conflicts of interest and how they have manifested in the draft Restatement; the Authors Guild’s January 2018 letter to ALI is a good read, as is the Stop ALI report published by the Content Creators Coalition.

Christopher Sprigman and his colleagues were unable to influence legislation through Congressional testimony, and, as an industry blogger points out, Sprigman counsel on the losing side of two major copyright cases, and supported his mentor’s losing argument in another.

It also must be said that David Lowery and Melissa Ferrick’s class action against Sprigman client Spotify and Lowery’s case against Rhapsody were probably among the most consequential copyright cases (along with BMG v. Cox) in the last five years. Some would say that the Lowery cases set the table for the Music Modernization Act….

So, he was unable to effect change through precedent-setting court cases as the law currently is, and one of the cases he lost might have “set the table” for an update to copyright law that is extremely harmful to those who hire him or have sponsored his research. And now, according to the letter from 10 of the ALI Restatement Advisors referenced above, the Restatement draft contains errors and omissions in the “black letter” law and in some cases contains the Reporters’ own definitions/interpretations in areas that are the subject of spirited debate within the field and portrays them as black letter law.

The Advisors come right out and say that the problems “are not random mistakes.”

“The problems we identify are not random mistakes scattered evenly across copyright’s ideological spectrum. Rather, each of these examples is consistent with and advocates for an interpretation of copyright that does not comport with federal statutory law and restricts copyright protection in a manner not intended by Congress.”

Everything about this Restatement says that it’s an industry-funded attempt to screw individual creators out of proper copyright protections, to the benefit of Big Tech – all while couching the purpose as social justice.

The only question left is, do Sprigman and his Associate Reporters know their role is as a useful idiot or not?

Join the conversation as a VIP Member