When my sister June battled a T-cell cancer, she had to have a blood transfusion. My husband also has a chronic disorder where he lost a great deal of blood. A transfusion was required in that case. I wish I could be more of a contributor to this circle of life, but because I suffer from chronic anemia, I have only been able to donate blood a handful of times. However, I am especially thankful for the man who made it all possible.

Dr. Charles R. Drew is known in medical circles as “The father of the Blood Bank”. The blood drives, bloodmobiles, blood transfusions, and means of treating all manner of blood disorders would not have been possible without his research and work.

Let’s first talk about why blood plasma is important. Plasma is commonly given to trauma, burn, and shock patients. In a Trauma Center, you have no time to type blood, you are just there to stabilize and hopefully save the patient. Since blood plasma doesn’t contain the cells or the platelets, it can be given to any blood type. Patients are also in shock because of the loss of blood volume, and plasma helps to restore this. Blood plasma is also administered to people with severe liver disease, multiple clotting factor deficiencies, immune deficiencies, and bleeding disorders.

We all know that our circulatory system is the superhighway for the body, and blood is the means of transport on that highway. Blood plasma is necessary for maintaining blood pressure (to keep the engine running smoothly), and volume. My mother used to use the term “poor blood” to refer to blood that lacks enough weight to transport anything. You are not adequately getting what the blood transports if the blood’s viscosity is lacking (hemophilia) or is overly abundant (blood clots).

Blood plasma supplies those critical proteins for blood clotting and immunity. It transports electrolytes such as sodium and potassium to our muscles, and it helps maintain a proper pH balance in the body, which supports cell function.

The National Institute of Health (NIH) maintains a “Profiles In Science” Library, which has several pages dedicated to Dr. Drew’s life story and his work. So, I will not rehash it all here, but focus on the work that transformed the entire world, and what his life story means to me. Unless noted, all quotes are from the NIH website:

“At Presbyterian, he [Drew] worked with John Scudder on studies relating to treating shock, fluid balance, blood chemistry and preservation, and transfusion. His main project with Scudder–and the basis for his dissertation–was an experimental blood bank at Presbyterian, opened in August 1939. In June 1940, Drew received his doctorate in medical science from Columbia, becoming the first African American to earn the degree there.

“In August, Presbyterian and five other New York hospitals had begun a collaborative effort to collect and ship plasma (the fluid, non-cellular portion of blood) to Britain. Although others had developed the basic methods for plasma use, Drew, as medical director, instituted uniform procedures and standards for collecting blood and processing blood plasma at the participating hospitals.”

Dr. Drew studied how to separate the plasma from the blood cells and platelets. He then discovered that not only could this frozen blood be reconstituted, but it could be stored and even transported safely.

“When the program ended in January 1941, Drew was appointed assistant director of a pilot program for a national blood banking system, jointly sponsored by the National Research Council and the American Red Cross. Among his innovations were mobile blood donation stations, later called ‘bloodmobiles.’ Ironically, as the blood bank effort expanded in preparation for America’s entry into the war, the armed forces initially stipulated that the Red Cross exclude African Americans from donating; thus Drew, a leading expert in blood banking, was ineligible to participate in the program he helped establish. The policy was soon modified to accept blood donations from blacks, but required that these be segregated.”

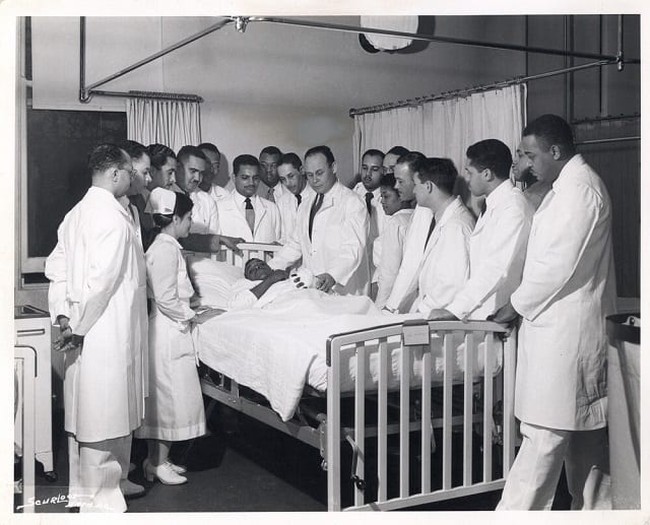

Charles Drew-Mobile Blood Bank (NIH Image)

This gives fresh insight into how true science can be hindered and dwarfed by prejudice, agendas, and even stupidity. Drew said this himself:

“This policy was maintained when the National Blood Donor Service officially began in November 1941, provoking protest from the black press and the NAACP, among others. In January 1942, the Red Cross announced that it would accept blood from black donors, but would segregate it. Drew, of course, objected to this policy—there was no scientific evidence, he said, of any difference between blood of different races, and the policy was insulting to African Americans, who were just as eager to contribute to the war effort as anyone else. He wrote and spoke about this frequently during the war years; as he noted in his Spingarn Medal acceptance speech in 1944, ‘It is fundamentally wrong for any great nation to willfully discriminate against such a large group of its people. . . . One can say quite truthfully that on the battlefields nobody is very interested in where the plasma comes from when they are hurt. . . . It is unfortunate that such a worthwhile and scientific bit of work should have been hampered by such stupidity.’ ”

Dr. Drew stood against injustice, without burning the whole thing down. In this time of segregation, he understood, like another of my heroes, Booker T. Washington, that racial progress would be built upon the achievement of excellence. However, that excellence needed to be protected and maintained. Dr. Drew understood the preciousness and precariousness of such achievement and he carried the weight of it for future generations.

Thankfully for us, Dr. Drew’s discoveries saved countless lives during World War II, because the Allied forces used Dr. Drew’s method of blood preservation to help treat wounded soldiers on the front lines. Dr. Drew created the nationwide structure of blood donation and transport throughout Great Britain and set up an identical network in the United States before stepping down to return to teaching.

Dr. Drew contributed greatly to racial progress and change by replicating himself.

“Once in charge of the department, Drew could at last pursue his larger ambition: training young African American surgeons who would meet the most rigorous standards in any surgical specialty, and to place them in strategic positions throughout the country, where they could, in turn, nurture the tradition of excellence. This, Drew believed, would be his greatest and most lasting contribution to medicine. The blood bank and other achievements were, he noted to a friend, only the preface in his life story. His style as a medical educator was memorable: an energetic, highly organized, demanding perfectionist, he was also genial, diplomatic, fair, and supportive. If he believed in a student’s potential, he would find a way to develop it. He searched out further training opportunities for his best residents, and occasionally underwrote their travel expenses to medical meetings that might benefit them.”

Sadly, what I see in the modern-day Civil Rights square is the replication of grievance, anger, and corruption, rather than excellence, achievement, and forward progress. We could all learn a lot from Dr. Drew’s strategy of building bridges, solidifying foundations, and investing in human capital rather than so-called righteous causes.

Another hallmark of Dr. Drew’s life were his beginnings. His pursuit of his life calling was less a direct path, and more a winding road. While this was indicative of the times in which he lived, it was also a wise strategy that represented a heart of service, and a depth of character.

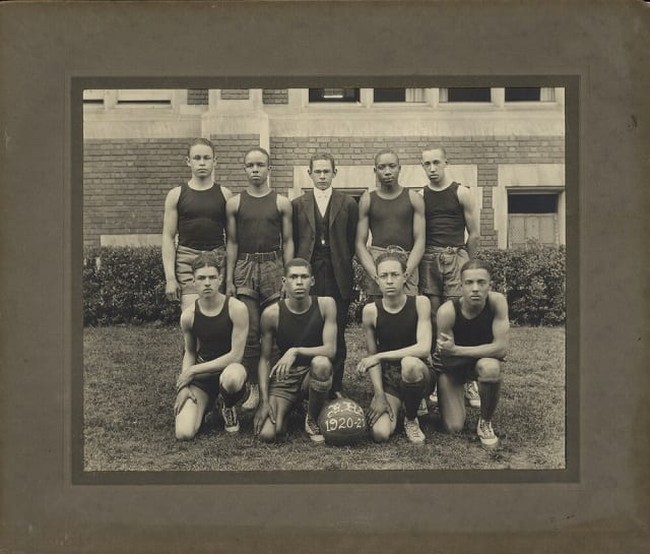

“Charles Richard Drew, the African American surgeon and researcher who organized America’s first large-scale blood bank and trained a generation of black physicians at Howard University, was born in Washington, DC, on June 3, 1904. His father, Richard, was a carpet layer and financial secretary of the Carpet, Linoleum, and Soft-Tile Layers Union–and its only non-white member. His mother, Nora Burrell Drew, was a graduate of the Miner Normal School, though she never worked as a school teacher. Charles and his younger siblings, Joseph, Elsie, and Nora, grew up in the largely middle-class and interracial neighborhood of Foggy Bottom (a third sister, Eva, was born after the family moved to Arlington, Virginia, in 1920.) Their upbringing emphasized academic education and church membership, as well as civic knowledge and personal competence, responsibility, and independence. At the age of twelve, Charlie (as he was called, even as an adult) became a paper boy, selling several Washington papers from a street corner stand; within a year, he had six other boys working for him and covering a wider area. As he got older, his after-school and summer jobs included supervising at city playgrounds, lifeguarding at the local swimming pool, and working construction jobs.”

Dr. Drew attended Dunbar High School and excelled at sports, winning several awards. Apparently, he was intelligent, but not necessarily an exceptional student. I can relate to that. I was smart, but I didn’t excel academically either. It took me a while to get to my true calling, but like Dr. Drew, I was able to get there.

Dr. Drew’s sports prowess allowed him to move forward in his goals. He attended Amherst College in Massachusetts on an athletic scholarship, and developed an interest in medicine through his biology courses. He graduated Amherst and in order to earn money for medical school, he took a job as athletic director and instructor of biology and chemistry at Morgan College (now Morgan State University), in Baltimore, Maryland. During his two years at Morgan, Dr. Drew’s coaching transformed the college’s mediocre sports teams into serious collegiate competitors. He did nothing halfway, but pursued excellence across the board.

“The racial segregation of the pre-Civil Rights era constrained Drew’s options for medical training. Some prominent medical schools, such as Harvard, accepted a few non-white students each year, but most African Americans aspiring to medical careers trained at black institutions such as the Howard University College of Medicine in Washington, DC, or Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee. Drew applied to Howard, but was not accepted because he lacked enough credits in English from Amherst. Harvard accepted him, but wanted to defer his admission to the following year. Not wanting to wait, Drew applied to the McGill University Faculty of Medicine in Montréal, which had a reputation for better treatment of minorities.”

Dr. Drew used his sports ability as a steppingstone to get to the next thing, and the entire human race is fortunate that he did. This teaches me that patience — not only in the process, but in the methods — is key in pursuing and achieving one’s goals and dreams. In our instant gratification culture, our young people need to learn that purpose and progress should be the markers of success, not necessarily the acquisition of the goal.

Another Black History icon who does not get the credit he deserves is the late Herman Cain. He said in the documentary Uncle Tom,

“Success does not come in a straight line… it’s a zig-zag.”

In Cain’s time, and especially in Dr. Drew’s, straight-line options were not even available; so, they took the route that allowed them to progress and achieve their goals; the focus was the goal, and not the path. We need to reinforce this lesson in our young people today.

Dr. Drew wrote in a January 27, 1947 letter to Mrs. J. F. Bates, a Fort Worth, Texas schoolteacher:

“. . . So much of our energy is spent in overcoming the constricting environment in which we live that little energy is left for creating new ideas or things. Whenever, however, one breaks out of this rather high-walled prison of the “Negro problem” by virtue of some worthwhile contribution, not only is he himself allowed more freedom, but part of the wall crumbles. And so it should be the aim of every student in science to knock down at least one or two bricks of that wall by virtue of his own accomplishment.”

Dr. Drew died on April 1, 1950, in Burlington, North Carolina. There is an anecdotal (and incorrect) story that he was refused a blood transfusion from a white hospital and that is what caused his death. The fact is Dr. Drew’s injuries sustained in a car accident were too severe. He was on his way to a teaching conference, to train medical students, which according to biographical information, is what he truly lived for.

“Despite the prompt and competent care he received from the white physicians at a nearby hospital, he was too badly injured to survive. Drew’s tragic death generated a persistent myth that he died because he was denied admission to the white hospital, or was denied a transfusion, but such stories have been debunked repeatedly. Though he died prematurely, Drew left a substantial legacy, embodied in his blood bank work and especially in the graduates of the Howard University College of Medicine.”

So, here’s my question: Why does the average American child, let alone Black children, know more about Kanye West than they know about Dr. Charles Drew? There are medical centers, societies, schools, institutes, and even a shipping vessel named after him. In 1981, he was honored with a U.S. postage stamp. Yet, this man’s contribution to the very thread of our lives does not get the widespread recognition it deserves.

For the sake of all our futures, I hope we will change that.

Sign up for our VIP program to get access to premium content for members only! Use code “OCONNELL” for a discount!