I argued with myself about writing about this seeing as how I’m a bit late to the party and it’s been reviewed and criticized over and over again, but I feel like if I don’t get this out I’m going to explode.

I saw the latest entry in Disney’s attempt at reviving its past glory by making everything a “live-action” remix of the original. I want to treat my take on it here like a compliment sandwich. The only problem is that the very well made and enticing bread is holding in what I can only describe as a mess of three-day-old compost.

The movie wasn’t bad, but it wasn’t at all good either.

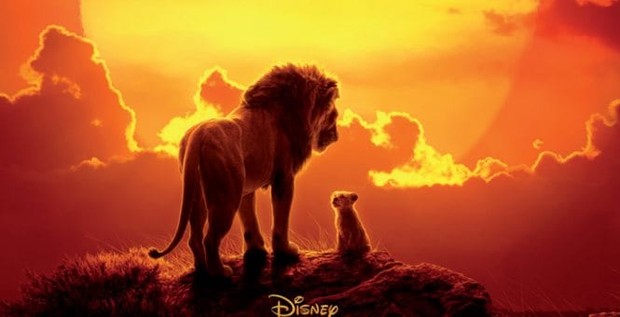

Let’s start with the good. The movie really shows off the extent of Disney’s abilities with CGI. There was so much attention to detail that I couldn’t tell what was CGI and wasn’t if they used real elements in the movie at all. In fact, they call it a “live-action” remake, but it’s mostly all CGI and we’re okay with them calling it “live-action” because it really does look like it. I was blown away by the littlest things like the waving of the grass and trees, the way the wind played with feathers of birds on the wing, and the way water splashed and soaked things when it was run through.

With that out of the way, I need to list why this movie had me leaving the theatre feeling melancholy, and I’m using that word specifically. I left sad.

I remember going to see The Lion King when I was around 10 and thinking I had just seen Disney’s greatest accomplishment. Not only was the animation stunning, but the African inspired music took me to the setting faster than any supersonic jet could, and the rid wasn’t just comfortable, it was exciting. The first moment that sun rose and the man came in with that drawn-out “Nants ingonyama bagithi Baba” I was stunned and enraptured.

Fast forward to now and I’m waiting for that amazing moment when the sun rose and the song began. The movie opens with an African setting with the sun still down. It’s peaceful and serene, and then it happens. The sun pops up and the music starts…and I laughed out loud. The sun pops up almost comically and the timing of the song takes you by surprise as if both the sun and the song were late and making a comedic entrance.

That was my first step back into the world of The Lion King and it wasn’t a good start. The laughter wasn’t mirthful. I was involuntarily laughing at something, not with it. Sadly this would define a lot of the rest of the movie for me. Many iconic moments from the film would find me somewhere between disappointed and ambivalent.

One example is the death of Mufasa, which is supposed to be a heart-wrenching moment in the movie. While it still produces feelings of sadness, none of it hits home like it did in the original. Even my fiance, who tends to feel emotions far better than I do, didn’t shed a tear. One of the main reasons was easy to deduce.

I felt like the characters didn’t care.

Sure they sounded sad, but for a photo-realistic movie with lions that have a concept of feudalism and existential crises, we can include a touch of facial animation to help carry emotion. Simba had the same look on his face during the trauma of trying to reawaken his dead father as he did when he was happily playing with Nala. It so removed me from the moment that I became detached from what should have been an affecting scene.

Facial expressions carry a lot of weight in a scene, and they just left these behind in favor of “realism.” You could easily still have the photo-realistic animals and still have human-esque facial expressions. I know this because they did it well in The Jungle Book remake.

Here’s a super-cut of some of the animations within The Jungle Book. Notice how the animals still maintain a realism to them while still expressing human emotion. A subtle lift or furrow of the brow here, a slight upturn of the mouth there. Emotion is translated without taking you out of the feeling that you’re looking at wild animals.

The Lion King fails to do this and results in a removal from the emotional weight of what the characters are going through. This was described perfectly by David Ehlrich of IndieWire:

Most often, the animation is just bland in a way that saps the characters of their personalities. Scar used to be a Shakespearian villain brimming with catty rage and closeted frustration; now, he’s just a lion who sounds like Chiwetel Ejiofor. Simba used to be a sleek upstart whose regal heritage was tempered by youthful insecurity; now he’s just a lion who sounds like Donald Glover.

Speaking of the voice-acting, it’s very hit or miss. I’m a fan of Donald Glover and I think he does everything he touches well, be it music or comedy. Here, however, I felt like Glover was somewhat flat. Like he tried to be there, but just couldn’t quite hit the mark.

Mathew Broderick, the original Simba, brought so much personality to the character that Glover had an uphill battle ahead of him, to begin with. However, there was a sort of detachment there that made me divest from the character. I’d like to chalk that up to the lack of expressive animations, but both James Earl Jones’s reprisal of Mufasa and Seth Rogan’s Pumba were incredible.

I get the impression that Glover wasn’t playing Simba, he was playing Glover playing Simba.

You felt this way for a few of the characters, especially Scar and the hyenas, but the largest character letdown, however, was Rafiki the baboon.

Robert Guillaume’s performance as 1994’s Rafiki is one of the most underrated voice acting performances cinema ever produced. Not only did Guillaume’s Rafiki really deliver a character you never forget, but he also added subtle habits and sounds to his voice that made you truly believe you were watching a baboon talk despite it being a toon.

Watch this interaction between Guillaume and Broderick during a scene that teaches a lesson that has stuck with me since I was a kid. Bonus: listen to the powerful music once Simba realizes who he is and what he must do. A superb scene all around.

The footage hasn’t been clipped from the 2019 version as of yet, but I can tell you that the scene from the recent version is like looking at a shadow of the real thing. This is in part because Rafiki has been neutered.

Despite the fact that Rafiki is considered a secondary character, the baboon acts as the connections between the old and the new, and when he moves, the movie moves with him. When he got excited, you felt it too. When he went to go find Simba personally, you felt like you were watching the agents of Heaven move to realign the players of Earth.

In 2019, however, Rafiki felt less. John Kani delivers Rafiki’s lines with a quarter of the personality of Guillaume, and the character feels like a Rafiki cut with water. For instance, 94′ Rafiki is known as something of a mystic who can deduce events from far away by means we don’t understand. The Rafiki of 2019 has lost that magical part of him.

The scene where he finds out Simba is alive is a perfect example of this. In 1994, Rafiki finds out Simba is alive by pondering debris in a turtle shell after receiving it from the wind. In 2019, he finds out Simba is alive because Simba’s hair was brought to him via ants, who got it from a dung beetle, who got it from a giraffe’s poop.

This loss of magic takes away from the potency of the discovery and epicness of the events that transpire. It goes from being a moment of fate to a moment of happenstance. We’re supposed to be in a world of talking lions and Kings, yet we’re consistently pulled back from the edge with attempts at “realism.”

Pardon the quality but watch the two scenes side by side and see which scene carries the emotion, excitement, and possibilities with it. Pay attention to the musical ambiance that acts as a storyteller all on its own as well as Rafiki’s reactions.

This article is already overlong. I could go into how Scar used to be a clever and devious villain of great magnitude but only comes off now as a flat villain who never grew out of his moody teenage phase, but I’ll wrap it up.

I said earlier in the article that I walked away feeling sad and I want to explain that now that I’ve laid out some details that I didn’t like.

This movie, at least to me, felt like Disney was trying to give me something it thought I and my generation wanted. It tried to deliver our childhood back to us but now in a more mature format. Personally, I didn’t want that at all. I don’t need a more realistic or mature Lion King. I’m happy with, and cherish, the one I got when I was ten.

And I know this movie was for the adults who grew up on the original Lion King despite it being a family film. So many moments and jokes were targeted at people like me that called back to the original, usually in fourth-wall-breaking moments by Timone and Pumba who practically acknowledge that the audience has seen this movie before.

My age has nothing to do with my love of the mystical and fantastical. I’ll watch family movies as a man as enthusiastically, if not more so than I did when I was young. I love the idea of a lion talking to a meercat about the quality of bugs, or a wise baboon teaching a young king an important life lesson. This doesn’t need to be mixed with so much realism that the magic begins to feel hollow.

It made me feel legitimately sad to watch something so exciting and welcoming from my childhood flicker and fade in the face of trying to grow up.

As C.S. Lewis said: “When I became a man I put away childish things, including the fear of childishness and the desire to be very grown-up.

Disney shouldn’t be afraid to make a magical movie for the kids with nods to adults like it used to. Trust me, the kid is still there, he just has a driver’s license and bills now. Both of them will still love it regardless.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member