We are entering today one of the most momentous weeks in a month that has seen momentous events, ending one of the weirdest U.S. presidential election campaigns ever.

Tuesday will be a blessed, scary, and hopefully decisive end to the longest campaign of all 60 presidential elections since George Washington was chosen by acclamation (twice). The last times everyone agreed.

The United States’ political, social, and cultural history, which modern American generations don’t seem to pay much attention to, has completely shaped how we live today. For instance, why vote on Tuesday, of all days, this late in the calendar year as winter looms?

We’ll get to that and more historical reasons for the quadrennial quandary that controls who runs the federal government and a growing population of more than 330 million between Leap Years.

Judging by the country’s political blood pressure and the intensity of media attention this time, we could have a record turnout when Tuesday’s ballots are added to those millions cast early in recent weeks.

As in the COVID election of 2020, mail-in ballots, which must be opened, verified, and counted individually, could delay the arrival of joy or anger for Donald Trump and Kamala Harris.

With a precision that comes from the knowledge that no one else is counting, the University of Florida Election Lab reports the most recent total count of early votes at 70,031,596 – 53 percent in person and 47 percent by mail.

The Federal Election Commission reported that 158,429,631 ballots were cast in 2020, about two-thirds of eligible voters, a U.S. record but one that looks pathetic against peer nations in the 80-70 percent range and other countries where voters show up despite terrorist threats.

Elections and Thanksgiving aside, November has been an important month historically. The World War I Armistice. One of history’s greatest art masterpieces – the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel by Michelangelo on his back – was unveiled in 1516. The British Stamp Act took effect in 1765, igniting the American Revolution. The Gunfight at O.K. Corral.

So, why do we vote on a Tuesday in November when so many other countries choose the weekend? Well, the 102 surviving Pilgrims who landed on Plymouth Rock in 1621 were basically religious refugees from Europe whose faith got them through 66 days of seasickness in the worst storm season for North Atlantic crossings.

Doing anything other than praying on the Sabbath was not possible. That tradition has continued in the U.S. When the Jan. 20 for Ronald Reagan’s second inauguration fell on a Sunday in 1985, the public swearing-in took place the next day.

Through the 1800s, the United States was a predominantly isolated rural society ruled by an agrarian calendar. Families were scattered over immense areas. Sunday was the business-free Sabbath. Monday was a travel day to town. Wednesday was market day there.

So, Election Day was standardized in the 1840s as the first Tuesday after the first Monday in November. Why November? Livestock aside, farms were basically shut down by then after the autumn harvest, while December and January’s harsh weather precluded most outdoor activities.

I didn't realize that, until then, states set their own election days for federal offices whenever they wanted during a six-week November-December window between holidays.

Awaiting actual results in those horse-and-buggy days makes the 2000 hanging-chad recounts and court fights seem like a Jiffy Lube oil change.

The 1860 presidential election has always seemed like a political presidential watershed to me. And, oh look! It came 164 years ago on this Wednesday, Nov. 6.

That was the first national confrontation between the two major parties that have shaped American politics ever since and endure today. That's because their ideologies and platforms have been – shall we say – malleable, adapting adeptly to society's changing times, interests, and priorities and starving third parties of lasting issues.

The Republican Party was created in Wisconsin in 1854 around the dominant issue of the day, slavery. In its first presidential contest, the anti-slavery GOP carried the day with Abraham Lincoln as nominee.

Lincoln was born in 1809 in Kentucky, the first president born outside the 13 original colonies. He was schooled briefly in Indiana and raised in Illinois to become the 16th president and, to this day, the tallest at 6-4.

An avid reader with an adventurous spirit, the 23-year-old Lincoln volunteered and fought with the Illinois militia in a short Indian uprising by a small local tribe. Chief Black Hawk and his braves lost the conflict, but left his name to a Chicago hockey team.

He helped fell trees to build a large river raft to carry farm goods down a local river and then the treacherous Mississippi to New Orleans. There, they took the raft apart and sold the logs to build houses in the first bustling big city the future president had ever seen.

Lincoln then walked the nearly 800 miles back to central Illinois.

Lincoln was a good, down-home speaker, and he liked wrestling, reportedly losing only one amateur match out of some 300.

Politics and wrestling are two combative skills of endurance and persistence of will that still seem to go together. Dick Cheney, Don Rumsfeld, Jim Jordan all wrestled, as did 13 presidents, including Washington, Andrew Jackson, Teddy Roosevelt, and Dwight Eisenhower.

Lincoln served one term in the Illinois state legislature and one term in the U.S. House. In 1858, he took on incumbent Democrat Sen. Stephen Douglas. They held now historic debates that year in seven of Illinois’ then-nine congressional districts.

One-hour opening statement by each man, then 30-minute rebuttals. All extemporaneous. No microphones. In Midwest summer heat.

Douglas claimed that new states should have the choice to implement slavery as a state right. Lincoln, an ardent slavery opponent, accused Douglas of planning to nationalize the human shackling. Lincoln supported states' rights but not when they infringed on fundamental human rights such as personal freedom.

Until the 17th Amendment in 1913 instituted popular voting, state legislatures elected senators. As today, Democrats controlled the Illinois legislature. Lincoln lost to Douglas 54 to 46.

But wait! They had a rematch.

The debates and Lincoln’s eloquence and plain-spoken common sense attracted national and statewide media attention. Joseph Medill, a conservative abolitionist and new owner of the Chicago Tribune, became an ardent advocate for him.

The new Republican Party convened in Chicago in May of 1860. New York Sen. William Seward was the clear front-runner for the GOP's presidential nomination. But on the first ballot, he failed to get a majority.

Other candidates swung to Lincoln, who showed his political prowess after the election. He named all four former party opponents to the Cabinet, including Seward as Secretary of State.

You may recognize that name from “Seward’s Folly.” The former senator was supposed to be assassinated, too, the night Lincoln was shot. But he wasn't in his boarding house room when the killer arrived.

So, Seward survived to carry out his dream of purchasing Alaska from the financially-strapped Russian czar in 1867.

The $7.2 million deal was much-mocked at the time. What possible value could there be in a frozen wasteland on the north side of Canada, even for more than $125 million in today’s money?

But the move evicted Russia, later the Soviet Union, from North America. It secured vast volumes of that gooey, smelly black stuff waiting underground for someone to find a lucrative use for it. And the purchase by the upstart Yankees so scared Britain that it granted independence to a reluctant Canada almost immediately.

All done by a Lincoln appointee.

Presidential campaigns back then were surrogate affairs. Things have changed somewhat since, you may have noticed. But it was considered bad taste for candidates to seek votes for themselves. Allies made their case to voters.

When slavery split Democrats into northern and southern wings in 1860, that election became a four-way race. The northern Democrat was old friend Illinois Sen. Stephen Douglas, who fared the worst.

There were 33 states then. Douglas won one of them, Arkansas. Lincoln needed 152 electoral votes. He got 180 from 18 states with only 39.7 percent of the splintered popular vote.

Welcome to the White House, Mr. President. Until 1933, Inauguration Days back then were in March. By March of 1861, seven states had seceded. Five weeks later, Confederates started the Civil War in South Carolina.

In 1863, Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing all enslaved people in the South.

As an attempt to begin national healing, for his 1864 reelection, Lincoln chose as his vice-presidential running mate a southern Democrat, Sen. Andrew Johnson of Tennessee.

That’s the only time a U.S. political party has nominated a bipartisan national ticket. It worked for the election. But not so well after, when GOP Congress met Democrat president. Post-presidency, Johnson became the only president to later serve in the Senate.

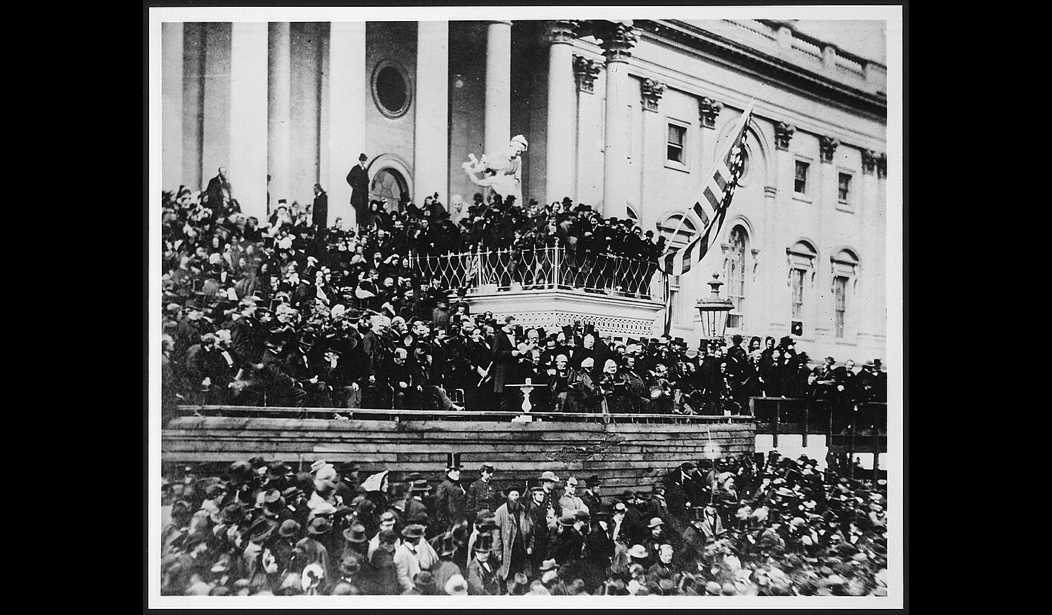

Lincoln’s second inauguration came outside the Capitol with John Wilkes Booth reportedly watching from nearby. Like much of what the self-educated Lincoln wrote, the speech was full of humanity, grace, and humility, and far shorter than today's wordy promise agendas salted with calculated applause lines:

With malice toward none with charity for all with firmness in the right as God gives us to see the right let us strive on to finish the work we are in to bind up the nation's wounds…

The ensuing celebration lacked Lincoln’s favorite food, chicken fricassee. But the 250-foot-long buffet table was laden with veal, venison, quail, oyster stew, and six flavors of ice cream, including Lincoln’s favorite, vanilla.

Twenty-five days later, the Civil War ended as the deadliest conflict still in U.S. history.

Thirty days after that inauguration, the Lincolns went to a play at Ford’s Theater. It was Good Friday.

Allegedly to see the performance better, the president’s bodyguard, John Parker, left his post outside the Lincolns' box. But he wound up in a nearby saloon.

Confederate sympathizer Booth had no trouble sneaking in behind the president with his .44 Derringer. The bullet entered the left side of Lincoln’s head, passed through the brain, lodging just behind the right eye.

The 56-year-old president, who had maintained the Union but would lose three of his four sons to illness, never regained consciousness and died the next morning.

(In a bizarre twist, Lincoln's eternal rest was interrupted 12 years later by a band of grave robbers who successfully absconded with the presidential corpse for some weeks, seeking ransom for the kidnapped body. Which explains why Abraham Lincoln now rests in a Springfield memorial in a coffin sealed within two tons of cement and steel.)

But before any of that came 1860 and the exciting, promising election 164 years ago this Wednesday. On that Election Day, Lincoln took on a full load of work in his Springfield law office.

Lincoln ate dinner at a nearby boarding house and then walked alone toward the telegraph office to find out if he was going to become president. Given the divisions, decisions, and challenges he endured, both personal and presidential, many now regard him as the greatest president in United States history.

That evening, as a kind of present to himself on the big day, Abraham Lincoln stopped at a local shop and bought himself a new pair of socks.