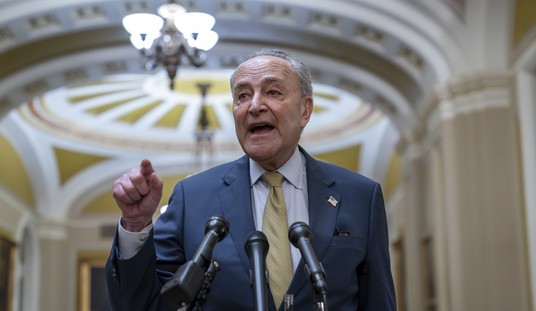

Law enforcement officials need backdoors to thwart encryption or else they will not be able to keep the public safe from terrorist attacks or crime. At least, that seems to be the major theme argued by law enforcement officials such as FBI Director James Comey, who stated:

Unfortunately, the law hasn’t kept pace with technology, and this disconnect has created a significant public safety problem. We call it “Going Dark,” and what it means is this: Those charged with protecting our people aren’t always able to access the evidence we need to prosecute crime and prevent terrorism even with lawful authority. We have the legal authority to intercept and access communications and information pursuant to court order, but we often lack the technical ability to do so.

A new report from Harvard University’s Berkman Center for Internet & Society, though, contradicts Comey’s claims, redefining the encryption debate and explaining how the explosion of internet connected devices provides law enforcement officials even greater opportunities to surveil terrorism suspects and other “bad guys.”

The so-called “Encryption Debate,” in a nutshell, is whether legislators should force companies to provide law enforcement access to a citizen’s electronic devices and communications in the event of a criminal or terrorism investigation. That is, whether legislators should mandate encryption “backdoors” while providing law enforcement the ability to access these “backdoors” pursuant to court orders. While this type of mandate may sound easy – after all, similar legislation exists for traditional landline communications services – it is both technically impossible and a deceptive argument.

Law enforcement officials have warned technology will lead to a “dark” world for surveillance since the early 1990s. These warnings are nothing more than law enforcement officials proverbially crying wolf. Their capacity to surveil citizens, whether lawfully or using methods operating on constitutional boundaries, has only increased since the early 1990s. And with the rapid explosion of the Internet of Things, this capacity will only grow.

The report emphasizes how connected devices, known as the Internet of Things, provide ample opportunity for law enforcement officials to conduct additional, and unanticipated surveillance. A number of connected devices, from fitness trackers, baby monitors and toys have embedded microphones, cameras or other hardware that could be accessed (or hacked) for surveillance purposes.

Law enforcement officials do not “need” backdoor access to electronic devices or other forms of electronic communications for the purposes of criminal investigations or anti-terrorism efforts. As the report notes, “Although the use of encryption may present a barrier to surveillance, it may not be impermeable. There are many ways to implement encryption incorrectly and other weaknesses beyond encryption that are exploitable.”

In other words, law enforcement can find ways around encryption. When talking about incorrect implementation of encryption or other weaknesses, what category of encryption poses the largest potential barrier for law enforcement officials?

To better understand the encryption debate, it is necessary to understand the different categories of encryption, for lack of a better term. For purposes of law enforcement investigations and the potential for surveillance “going dark,” there are two different categories of encryption: End-to-end and Device.

The first category of encryption, end-to-end, occurs when a communication – be it a text message, email, or phone call – is encrypted by the sender and only the sender and the recipient have the information necessary to decrypt the communication. In this particular case, the entire communication is unreadable by anyone other than the sender and the recipient. Apple cannot read the communication, nor can Google, nor can law enforcement officials.

The second category of encryption, device, only encrypts the information found on a specific electronic device. It generally applies to smartphones and tablets. It does not encrypt calls. It does not encrypt email hosted by third parties, such as various webmail services. It does not encrypt web browsing habits.

Instead device encryption, whether native to devices or through software installed by the user, secures data housed on the actual device. This may include documents, pictures and all other file types on the device. It prevents both law enforcement and bad actors, such as hackers, from accessing the device without the user’s key – the passcode or password the user created when encrypting the device.

End-to-end encryption poses the largest barrier for law enforcement, as it obscures data between two communicants. While it poses the largest barrier for law enforcement, it does not prevent them from accessing the communications necessary to detect or investigate crimes or terrorism. This is because service providers have not adopted end-to-end encryption as a widespread practice. “Current company business models discourage implementation of end-to-end encryption and other technological impediments to company, and therefore government, access.”

While the report focuses on various companies’ interest in unencrypted information, primarily on the need for unencrypted data to drive revenue through targeted marketing, it also addresses other barriers for widespread adoption. Some of these other barriers can be summed up in one word: convenience.

For the electronic communications to go truly dark, everyone would have to adopt end-to-end encryption services, such as Pretty Good Privacy (PGP), Crypter for Facebook Messages, WhatsApp or other such services. Senders and recipients would need to use the same software, understand how to generate keys, and so on. All these steps would add “complexity and friction that is simply too much for most users to bother.” In other words, the additional steps necessary to encrypt communications would require time and effort that most individuals are not willing to invest for the sake of convenience.

How should the encryption debate be answered? That’s a good question. One the Obama administration has decided is best put on hold, for now. Given that law enforcement’s push is to weaken encryption, the best answer may be “nothing.”

What is certain, though, is the need for security and confidence in today’s technology-based marketplace, along with the need to protect individuals’ privacy from prying eyes. If legislatures demand added encryption vulnerabilities, the web and e-commerce marketplaces will become far scarier places to do business. States and the federal government need both to protect and encourage strong encryption practices, which will keep the web, e-commerce, and the individual as secure as possible.

Jonathon Hauenschild is a legislative analyst for the Center for Innovation and Technology at the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC).

Join the conversation as a VIP Member