An American Hero: Sergeant “Jumpin’ Joe” Beyrle

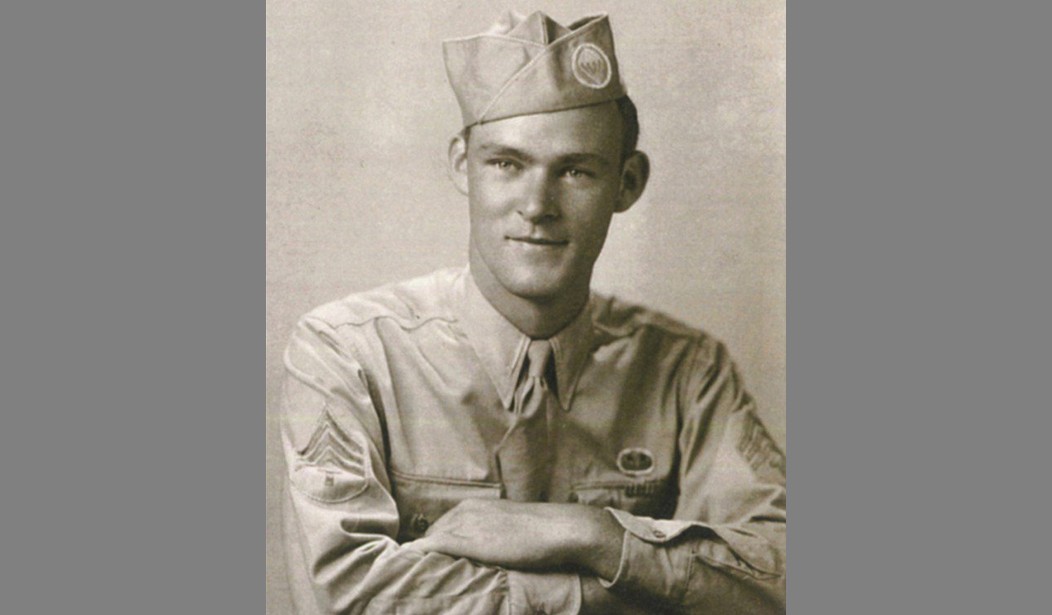

The young fellow in the uniform pictured just above looks like a calm, mild-mannered young man, a conservative young soldier, the solid, reliable type. Doubtless, a young man of promise, who will go on after his Army service to manage a hardware store or perhaps sell cars.

That is not the case; this is the young Joseph Beyrle, one of America’s premiere Second World War tough guys, a guy the Germans couldn’t keep locked up, and the only Allied soldier to make his fellow troops feel inadequate in both the U.S. Army and the Soviet Red Army.

His Maculate Origin

Joseph Beyrle was born on August 25, 1923, in Muskegon, Michigan. His parents, William and Elizabeth Beyrle, were a factory worker and a housewife, respectively. Joseph’s father lost his job early in the Great Depression, after which the Beyrles were evicted from their home and moved in with Joe’s grandmother.

Growing up in the Depression had its challenges, as my parents often described in detail. The Beyrles dealt with things as many other folks did in those days: by finding a way to get by. Joe’s two older brothers dropped out of high school to join the Civilian Conservation Corps, so Joe was able to finish high school and even win a full scholarship to Notre Dame.

But then, Pearl Harbor happened, and young Joe passed up the Notre Dame scholarship to join the U.S. Army’s 506th Parachute Infantry regiment. The 506th was, of course, part of the 101st Airborne Division and the same regiment from which came the men described in Stephen Ambrose’s book "Band of Brothers."

Suffice it to say that the expectations of U.S. Army soldiers, and young American men in general, were a little different in those days.

See Related: Half of Men Feel Pressured to Act Manly - They Shouldn't Have to Act

US Army: We'll Solve Our Recruiting Woes by Slashing 24K Positions

His Adventurous Career

Training for the paratroops was some of the toughest training the U.S. Army did in World War 2. Beyrle got through the Camp Toccoa training with little trouble. Paratroopers were required to make a certain number of jumps to qualify, and it seems some of Joe’s fellow soldiers weren’t terribly keen on it, so Joe would take their places on training jumps, getting them their jump credit on the sly; this earned him the nickname “Jumpin’ Joe.” Once he was at last a fully qualified paratrooper, he was sent forthwith to Ramsbury, England, to continue field training.

There was one problem: Exercise maneuvers, sand-table classes, and field problems bored Sergeant Beyrle. There was a need for a paratrooper with uncommon courage and determination to jump into German-occupied France with gold for the French Resistance. Sergeant Beyrle apparently thought this would be, as the Brits say, “a bit of a lark” and so volunteered – twice – for a mission that would have gotten him shot if he were captured by the Germans.

It was on The Longest Day, though, that Sergeant Joe Beyrle’s real odyssey began.

His One-Man War

On the very early morning of June 6th, 1944, Joe Beyrle found himself along with many of his fellow paratroops, in a C-47 transport plane bound for Normandy. On the approach to the drop zone, the C-47 came under heavy fire, forcing the men to jump early and, like so many other members of the 101st and 82nd Airborne divisions in that exercise, to be scattered and lost.

German troops in the French village of Saint-Côme-du-Mont woke early that morning to find their weather forecast was lacking, as they did not expect to find it was raining Michigan badasses outside. Jumpin’ Joe came down on the roof of the church and, while under fire from a German rifleman, calmly cut himself free of his parachute, loaded his M1 carbine, and started killing Germans.

One of Beyrle’s unit missions was to blow up the power substation in Saint-Côme-du-Mont. Alone, Jumpin’ Joe nevertheless had his carbine, some Thermite, and a huge pair of solid titanium ones, so he found the substation, killed a squad of Germans around it, and blew it up himself. He used his supply of grenades to kill another squad of Germans who came to investigate, then blew up a bridge to prevent more Germans from reinforcing the village or the troops defending Utah Beach.

He then stumbled across a German machine-gun position and, finding himself facing ten armed and angry German soldiers, was forced to surrender.

The trouble was that the Germans didn’t know they were trying to imprison a demon in a corncrib.

On the march back towards a German POW collection point, the column Jumpin’ Joe was part of was bombed and strafed by aircraft. Whose aircraft it was remains unknown to this day, but Joe used the opportunity to escape – after being hit by shrapnel and blown into a ditch, he legged it for the horizon but was captured by a German patrol after twelve hours on the lam.

Joe was then loaded into a truck bound for the French town of St. Lo, which was still held by the Wehrmacht. The truck was strafed, this time by Allied fighter-bombers. Joe used the resulting chaos to attempt escape again but was caught.

That night, the Allies bombed St. Lo. Sergeant Beyrle somehow survived that as well.

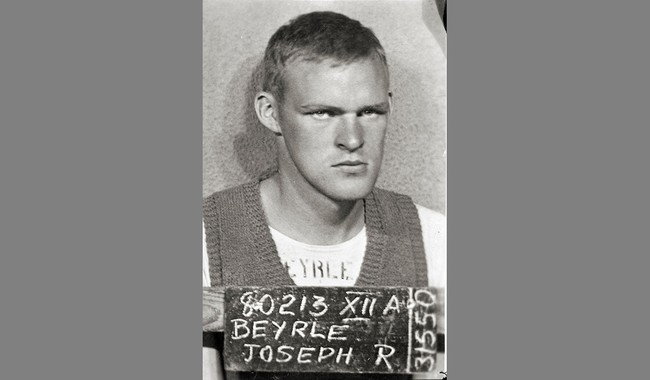

Finally, it dawned on the Germans that this stubborn guy from Michigan was going to try to escape again, no matter how much they abused him. In September 1944, Joe was sent to a POW camp in Poland containing mostly Russian soldiers. Take a look at Joe’s POW photo, and you can understand how the most hardened German soldiers were intimidated by the pure hate radiating from this great American.

The Germans treated Russian prisoners even worse than Americans, but that didn’t stop Jumpin’ Joe from enlisting some fellow American prisoners in his next escape plan. One night in November, the four cut through some barbed wire and hopped on a train that they thought was headed east toward advancing Soviet troops. Bad luck, though, as they caught the wrong train and found themselves in Berlin and ended up in the hands of the Gestapo.

About that interlude, Joe later related:

In the next seven to 10 days we found out everything we had heard about the Gestapo was true. We were interrogated, tortured, kicked, knocked around, walked on, hung up by our arms backward, hit with whips, clubs and rifle butts. When you thought they could do no more, they would think of other ways to torture you. When you would slip into semiconsciousness, they would start again. This went on for days at a time, and then they would dump you into a cold, dark cell with no sanitary facilities and dirty from a previous occupant.

Eventually, a Wehrmacht officer found out about the Gestapo’s prisoners and protested, claiming the Gestapo had no jurisdiction over military prisoners of war, and so Jumpin’ Joe found himself out of the Gestapo frying pan and into a larger Wehrmacht frying pan known as Stalag Luft III.

Stalag Luft III had been opened in Poland in 1942 and was considered escape-proof. Once Jumpin’ Joe got his strength back from the Gestapo abuse, he put that assertion to the test. In January of 1945, Joe and three other allied POWs broke through a wall and ran for it. Joe’s three companions were shot and killed, but Joe escaped.

On the run in frozen Poland with a pack of German troops and dogs on his trail, Joe plunged into an icy river and followed it downstream for several miles to throw off the pursuit. Finally, he reached the Soviet lines.

Approaching a Soviet tank battalion, Joe raised his hands, showing a pack of American Lucky Strike smokes in one hand, and shouted, “Amerikansky tovarishch!” (American comrade!)

Once more, at least in (sort of) friendly hands, Jumpin’ Joe was taken to the battalion commander, one Aleksandra Samusenko, the only female tank commander of World War Two. Recognizing each other’s inherent badassery, the two quickly established a rapport despite Joe’s minimal Russian. Samusenko found Jumpin’ Joe’s request to join her troops convincing, and the fact that he had demolition experience was a plus. Thus, Jumpin’ Joe Beyrle became the only soldier to serve in both the American Army and the Red Army in the entire conflict.

Later that month, the Red Army battalion Jumpin’ Joe was assigned to liberate Stalag Luft III. That had to be satisfying. But in February, Jumpin’ Joe’s unit was attacked by German aircraft, and Joe was wounded.

The Red Army sent Joe to a Soviet hospital in Landsberg an der Warthe. While there, word got out that an escaped American POW was serving with the Red Army, and so in a Forrest Gump-like moment, Joe received a visitor – one Marshal Georgy Zhukov, who arranged for Joe to be sent to the American Embassy in Moscow.

There was a problem – Joe had been declared killed in action back in 1944, and his family was notified by telegram. There had even been a funeral Mass held in Muskegon. Joe was held under guard until his fingerprints were verified and then had a long trek to Odessa, Cairo, and Italy before finally arriving back in Muskegon in April 1945.

Joe’s awards included:

- Combat Infantryman Badge

- Parachutist Badge with one Combat Jump Star

- Bronze Star

- Purple Heart with four Oak Leaf Clusters

- Prisoner of War Medal

- Army Good Conduct Medal

- American Campaign Medal

- European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal with 2 Service Stars and Arrowhead Device

- World War II Victory Medal

- Croix de Guerre 1939-1945 with Palm (France)

- Order of the Red Banner (Soviet Union)

- Order of the Red Star (Soviet Union)

- Medal "For the Liberation of Warsaw" (Soviet Union)

- Medal "For the Victory over Germany in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (Soviet Union)

- Medal of Zhukov (Soviet Union)

- Jubilee Medal "50 Years of Victory in the Great Patriotic War 1941–1945" (Russia)

His Golden Years

Home at last in April of 1945, Joe celebrated V-E Day in Chicago. The next year, he married JoAnne Hollowell and started a 28-year career with the Brunswick Corporation and, by all accounts, led an uneventful post-war life. One exception to that peaceful existence came on the 50th anniversary of D-Day when he was invited to the Rose Garden to receive medals from U.S. President Bill Clinton and Russian President Boris Yeltsin.

Joseph Beyrle passed away in his sleep on December 12, 2004, during a visit to Toccoa, Georgia, where he had been trained as a paratrooper. On the wall of the church Jumpin’ Joe landed on in Saint-Côme-du-Mont, France, there is a plaque that bears the following words in French and English:

From this spot on June 6th, 1944, T/4 Joseph Beyrle, I CO, 506 PIR, 101 ABN DIV began his war for the liberation of the people of Europe.

No soldier ever was awarded a finer – or more appropriate – epitaph.