The Derek Chauvin defense team filed their legal arguments in support of a motion for a new trial based on his claims that prejudicial pretrial publicity in his case made it impossible for him to receive the constitutionally mandated “fair trial” in Hennepin County, and that juror misconduct during the case deprived him of the right to a fair and impartial jury.

The 53-page memorandum does an effective job at cataloging the shortcomings of Judge Peter Cahill in addressing and resolving these issues. While it is a near certainty that Judge Cahill will deny the motions for a new trial and a change of venue — Minneapolis would likely burn if he granted them — and a Minnesota appeals court is likely to do the same, the motions nevertheless lay the groundwork for some serious legal arguments in the months ahead. Courts are going to have to grapple with the problem of how to deliver to an accused defendant the fair trial before an impartial jury under the Constitution in today’s interconnected and social-media-dominated world.

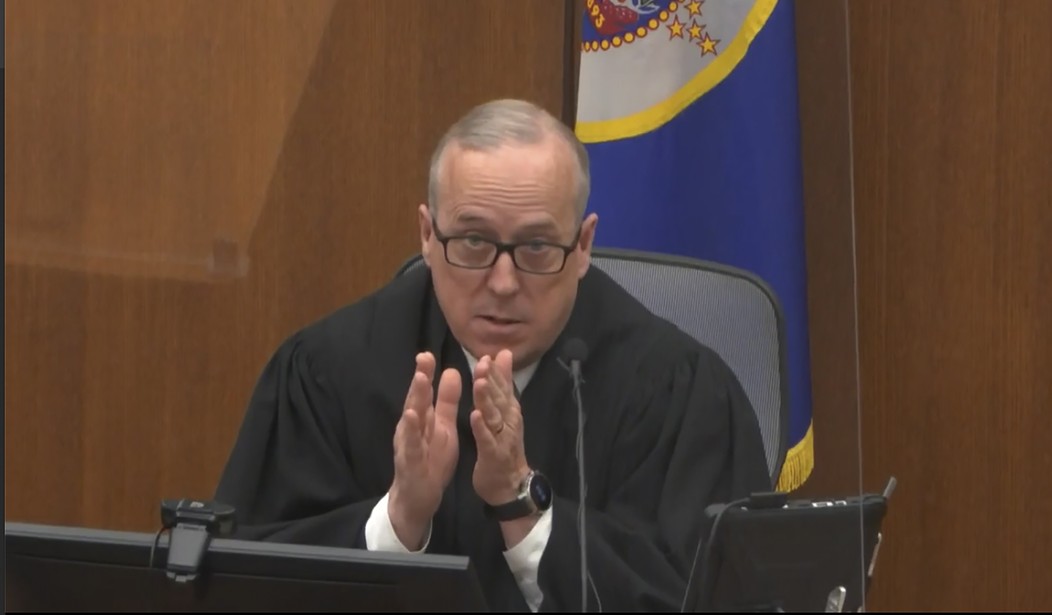

Right at the start, the memorandum focuses on what I have always thought was the fatal error by Judge Cahill in his somewhat cavalier approach to dealing with Chauvin’s motion for a change of venue based on prejudicial pretrial publicity. The memorandum quotes Judge Cahill’s in-court comments as follows:

As far as change of venue, I do not think that that would give the defendant any kind of fair trial beyond what we are doing here today. I don’t think there’s any place in the state of Minnesota that has not be subjected to extreme amounts of publicity in this case.

These were comments made by Judge Cahill during jury selection after the news reports and news conferences held in the immediate aftermath of the announcement that the City of Minneapolis had settled a civil action brought by George Floyd’s family by paying $27 million.

This characterization by Judge Cahill reflects a gross misunderstanding of his obligations to ensure that Chauvin received the constitutionally required “fair trial.” At the time I characterized his comment as a “This is the best fair trial we can give so that’ll have to be good enough” standard.

It is beyond the scope of this article to explain in detail the legal standards that exist with regard to granting a change of venue motion based on extensive pretrial publicity and its impact on the pool of potential jurors. The subject comes up only rarely where the circumstances are such that the motion was actually granted due to pretrial publicity so extensive as to make finding a fair and impartial jury difficult if not impossible. Only a small handful of cases have ever reached the Supreme Court on this issue.

In one of the Enron cases, the denial of a change of venue motion made by defendant Jeffrey Skilling made its way to the Supreme Court in 2010. The Court’s opinion in Skilling provides the most comprehensive analysis — and most recent — on the rights of a criminal defendant and the obligations of the trial court with regard to dealing with questions of prejudicial pretrial publicity and the right to an impartial jury.

Another extraordinary case was the trial of Timothy McVeigh and the bombing of the Oklahoma Federal Building in Oklahoma City. McVeigh’s trial was moved from Oklahoma City to Denver. Both sides agreed that the pretrial publicity made it impossible to find a fair and impartial jury for McVeigh in Oklahoma, even though the federal district court could draw jurors from the entire state of approximately 3.5 million people.

There is currently pending before the Supreme Court the Boston Marathon Bombing case, United States v. Tsarnaev. After Tsarnaev was convicted and sentenced to death in the federal district court in Boston, the Court of Appeals for the First Circuit reversed parts of his case, including the death penalty, and sent the case back to the district court for partial retrial. The trial court judge had denied defense motions for a change of venue based on his intention to conduct an intensive screening of jurors for bias or prejudice during the selection process. Among the reasons for reversing Tsarnaev’s sentence was the Appeals Court’s conclusion that the trial judge had not conducted a screening consistent with his representations. The Court found that Tsarnaev’s right to a fair trial before an impartial jury had not been met. The government appealed the First Circuit’s decision, and the Supreme Court will hear arguments during its next term beginning in October.

The Tsarnaev case highlights the fact that there are really two inquiries at issue here — the refusal of Judge Cahill to act on the issue of prejudicial pretrial publicity that he recognized to be a problem, and the failures of Judge Cahill to adequately screen out biased or prejudiced potential jurors when assembling what is supposed to be an “impartial jury” for trial.

Chauvin’s motion deals with both issues but starts with Judge Cahill’s own comments that prejudicial pretrial publicity was present and could not be denied. The lack of an alternative venue was his basis for denying the change of venue motion. The motion makes the point that the Minnesota Rule providing for a change of venue does not give discretion to the Judge to deny a motion when a fair trial is likely not possible in the location where it is set to take place. Rule 25.02, subd. 3 states:

Subd. 3. Standards for Granting the Motion. A motion for continuance or change of venue must be granted whenever potentially prejudicial material creates a reasonable likelihood that a fair trial cannot be had. Actual prejudice need not be shown.

This is where Judge Cahill’s comments before the trial, and during jury selection, become a problem. Nowhere in the Rule is it contemplated that the question turns on an issue of alternative locations and whether a more fair trial is possible somewhere else. The Rule says the change of venue motion “must” be granted whenever there is a reasonable likelihood that a fair trial cannot be had.

The motion also makes the key point — not understood by the media and many in the legal punditry — that the “impartial jury” right in the Sixth Amendment, belongs only to the defendant, and not to the prosecution. There was a concerted campaign launched in the community and the media to ensure that the trial takes place in Hennepin County because Floyd was black, and the racial composition of Hennepin County made it the only county in Minnesota where there was a high probability that the jury would include one or more black jurors.

I have not listened to or read the transcripts of the days of jury selection during which Judge Cahill questioned prospective jurors. Until I do so I’m not going to opine on his performance in that regard.

But I will leave readers with the following lengthy passage from Irwin v. Dowd, a 1961 Supreme Court case that provides the foundation for much of the Supreme Court’s more recent jurisprudence on the issue of juror impartiality [I’ve eliminated citations in the passage to shorten it]:

In essence, the right to jury trial guarantees to the criminally accused a fair trial by a panel of impartial, “indifferent” jurors. The failure to accord an accused a fair hearing violates even the minimal standards of due process. A fair trial in a fair tribunal is a basic requirement of due process. In the ultimate analysis, only the jury can strip a man of his liberty or his life. In the language of Lord Coke, a juror must be as “indifferent as he stands unsworne.” His verdict must be based upon the evidence developed at the trial. This is true regardless of the heinousness of the crime charged, the apparent guilt of the offender, or the station in life which he occupies. It was so written into our law as early as 1807 by Chief Justice Marshall “The theory of the law is that a juror who has formed an opinion cannot be impartial.”

It is not required, however, that the jurors be totally ignorant of the facts and issues involved. In these days of swift, widespread and diverse methods of communication, an important case can be expected to arouse the interest of the public in the vicinity, and scarcely any of those best qualified to serve as jurors will not have formed some impression or opinion as to the merits of the case.

This is particularly true in criminal cases. To hold that the mere existence of any preconceived notion as to the guilt or innocence of an accused, without more, is sufficient to rebut the presumption of a prospective juror’s impartiality would be to establish an impossible standard. It is sufficient if the juror can lay aside his impression or opinion and render a verdict based on the evidence presented in court.

The adoption of such a rule, however, “cannot foreclose inquiry as to whether, in a given case, the application of that rule works a deprivation of the prisoner’s life or liberty without due process of law.” As stated in Reynolds, the test is “whether the nature and strength of the opinion formed are such as in law necessarily . . . raise the presumption of partiality.

I do not think the state of Minnesota and Judge Cahill met this standard in the trial of Derek Chauvin.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member