It was the summer of 1980, and I was riding my battered old Honda (a real collection of spare parts traveling in formation, with 8"-over forks and apehanger handlebars) down Highway 57 in eastern Iowa, trying to outrun an incoming thunderstorm. The leading edge of the storm was catching up with me, and I was pushing the old machine to its limits as the first drops of rain fell around me. I was coming from visiting a young lady in Aplington and was trying to beat the storm into Parkersburg.

The sky was looking ugly in the rearview mirrors. I was leaning down over the tank, trying to lower my profile, when I heard a slowly growing roar. I looked around to see a tornado, a small one but still troubling, following me up the highway.

I rode into the ditch, laid the bike down, and laid down behind it. Fortunately, the twister veered off the north, leaving me untouched, and petering out somewhere in the farm country north of Parkersburg.

That was my lucky day, but the recent twisters that hit Iowa, Nebraska, and Oklahoma on Friday and Saturday gave me some pertinent reminders of what growing up in tornado country was like.

See Related: Video: Incredible Tornadoes Wreak Havoc Across the Heartland

Twisted: A Second Night of Monster Midwest Tornadoes Brings Devastation to Oklahoma

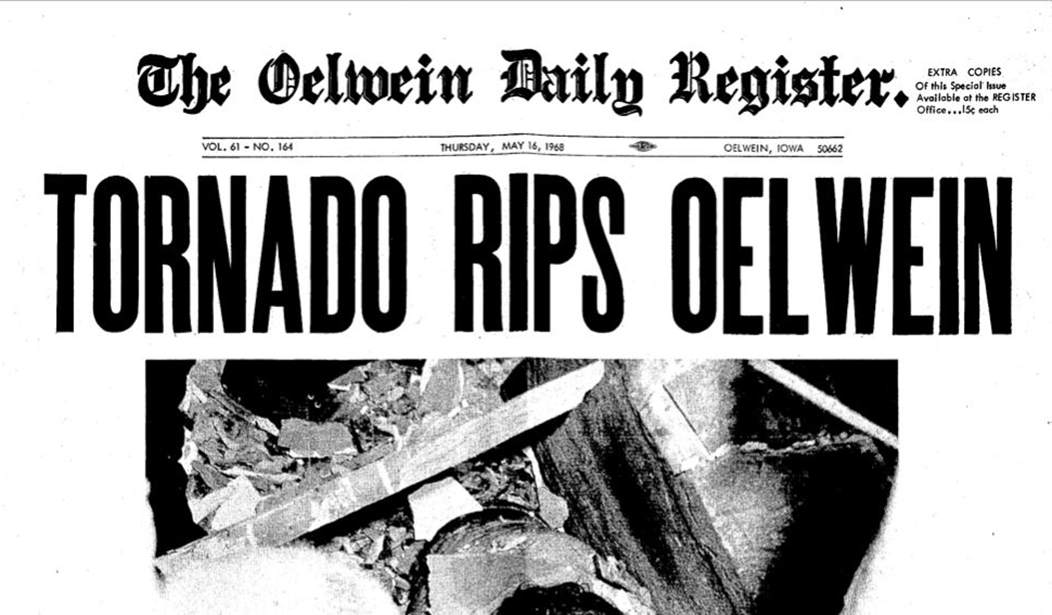

Which brings me to May, 1968. I was six years old, but I nevertheless have some vivid memories of that spring and the storms that raked eastern Iowa on May 15th and 16th of that year.

Charles City was the first town hit.

The tornado grew larger and more intense as it approached Charles City, striking the city at approximately 4:50 PM CDT. The huge tornado (approximately a half mile wide) passed directly through town from south to north. The tornado destroyed, 372 homes and 58 businesses, 188 homes and 90 businesses sustained major damage, and 356 homes and 46 businesses sustained minor damage. Eight churches, 3 schools were damaged or destroyed, the police station was heavily damaged, and 1,250 vehicles were destroyed. About 60 percent of the city was damaged by the tornado. Damage was estimated up to $30 million.

But the one that hit my parents hard - me not as much, as at that time I didn't have as good an understanding of the implications, being only six - was the one that hit the eastern Iowa town of Oelwein. Four of my parents' five children had been born there, including me, and while farming near Fairbank my parents did most of their trading in that town.

At 4:57 PM CDT, another F5 tornado touched down one mile southwest of Oelwein. The warning sirens sounded for only 15 seconds before power failed. The tornado moved in a northward direction up Oelwein's main business street (North and South Frederick) and a parallel street a block east (First Avenue Southeast). It destroyed 68 homes. Another 132 homes sustained major damage and 600 sustained less damage. Every business in the district suffered damage including 51 that were destroyed. Two churches, an elementary school, and the middle school were destroyed. Some persons said that they saw more than one tornado.

This tornado moved north through the western part of Maynard. About five square blocks were virtually leveled. More than 25 houses and the new $120,000 Lutheran church were destroyed.

Thirteen people died in the Charles City tornado. Four died in the tornado that hit Oelwein and Maynard. There were many more injured, and millions in property damage. And these tornados were just part of a much larger outbreak.

The Saturday following the storms - May 18th - I climbed in the back of my father's old station wagon and rode with my parents over to Charles City and then to Oelwein. My parents knew people at or near both towns and wanted to see how everyone came through.

Charles City was the worst. Dad, a WW2 bomber-navigator, said the city looked as though it had been bombed. I remember flattened buildings, upside-down cars, and wrecked houses, and even today, over half a century later, I can still see the town in my mind's eye. Oelwein was a little better, but not much, as the tornado had gone right up the town's main drag. I doubt there was an unbroken pane of glass in that town of my birth.

It all gives one a sense of perspective. Nature in all its glory operates at a scale that it's difficult for us to wrap our heads around; while the climate-change Chicken Littles are hand-wringing over our greenhouse gas emissions, one good volcano can leave us in the dust when it comes to the climate. And a tornado, or any other major storm, makes the efforts of humans look pretty puny by comparison.

Through the years I lived east of Denver (another area prone to tornadoes), I developed the habit of taking visitors to the area to a high spot on Smokey Hill Road where they could look over the city to the Front Range beyond, the mountains making one of America's major cities look downright tiny. It's the same with storms; these are huge, natural processes that we are pretty helpless in the face of.

Here in the Great Land, tornadoes and even thunderstorms aren't all that common. These kinds of storms generally arise when warm air masses hit cold air masses, and we mostly have only cold air masses here. But we do get the occasional rumbles of thunder, and while tornados aren't unheard of, they are rare, and Alaska's sparsely populated nature means that when they do happen, they usually just stir up some brush.

Even so, there's nothing like a big storm to make us humans feel kind of puny by comparison.