Thieves have always been with us in one form or another. Sometimes it is actually an act of desperation. In John Steinbeck’s epic novel The Grapes of Wrath, towards the end of a saga, he depicts a young boy talking about his starving father:

The boy was at her side again explaining, “I didn’ know. He said he et, or he wasn’ hungry. Las’ night I went an’ bust a winda an” stoled some bread. Made ’im chew ? er dowp. But he puked it all up, an’ then he was weaker. Got to have soup or milk. You folks got money to git milk?”

It’s a common theme in fiction, and there’s no doubt it happened throughout history. From Les Miserable to Steinbeck, the literary world is full of people driven to desperate theft to survive.

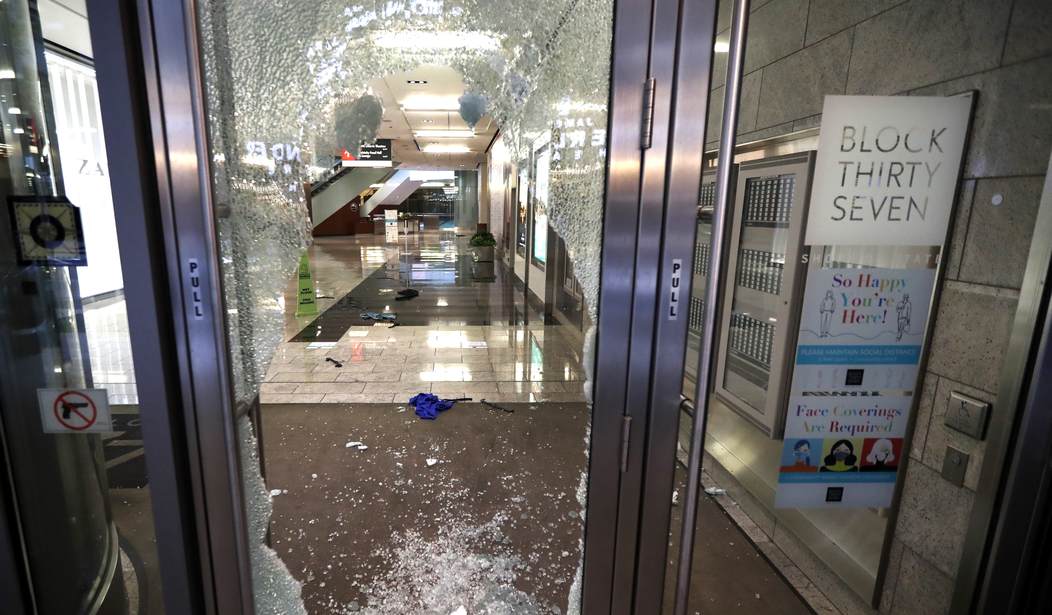

But theft in our major cities, theft from retail establishments, is spiking, and hunger has nothing to do with it.

A recent video on Twitter showed a supermarket employee tussling with a shoplifter who had filled her bag with items. As the employee pulled the bag from her hand, she cried, “I have to feed my family!” That’s a common refrain from shoplifters these days, echoed in media headlines proclaiming that people have turned to stealing to put food on the table—despite a U.S. social safety net that includes $185 billion in spending on food stamps and other nutrition-assistance programs. In truth, America’s exploding shoplifting problem predates our current economic difficulties. Much of the stealing, store owners and security experts say, has less to do with putting food on the table than with a rise in organized theft, and it’s having a particularly adverse effect in cities where criminal-justice reforms have made it easy to get away with.

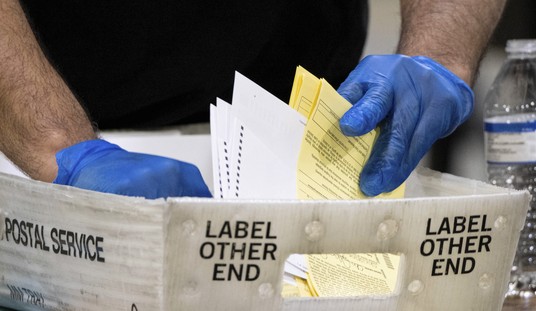

In California, the whole mess started with Proposition 47, a ballot initiative that reduced these offenses to misdemeanors:

- Shoplifting, where the value of property stolen does not exceed $950

- Grand theft, where the value of the stolen property does not exceed $950

- Receiving stolen property, where the value of the property does not exceed $950

- Forgery, where the value of forged check, bond or bill does not exceed $950

- Fraud, where the value of the fraudulent check, draft or order does not exceed $950

- Writing a bad check, where the value of the check does not exceed $950

- Personal use of most illegal drugs

Similar laws have been voted on or passed by state legislators in other Democrat-controlled states. And it’s costing businesses millions.

Retail theft in America has grown to a $94 billion epidemic, according to the National Retail Federation—a staggering 90 percent increase since 2018. Retailers say that the problem gained momentum about a decade ago, when states began decriminalizing low-level shoplifting, raising the value of goods that a person must steal to enable prosecutors to bring felony charges. More than two-thirds of states now treat shoplifting as a misdemeanor if someone boosts less than $1,000 in goods, and 15 states have raised their limit to $1,500 or more. More than 70 percent of surveyed retailers reported that shoplifting spiked in their stores after these changes. Bail reforms that free without bond those arrested for shoplifting have also contributed to the problem. An official of the Association of Certified Anti–Money Laundering Specialists says that retail theft is now “a low-risk and high-reward line of business.”

To sum all this up: People steal because they get away with it. Retail stores are increasingly reluctant to intervene, in some cases making non-intervention a corporate policy. And in some cases, retail workers aren’t even bothering to report crimes because the very effort is futile.

This is why they steal.

In the late Seventies, when I was in high school, I worked part-time, later full-time, at a Woolco store in eastern Iowa. It was a great job for 17-year-old me; I thought the hourly wage of $2.90 to be pretty good, especially since I was paid in cash every Friday afternoon, and I worked the counter in sporting goods, so my job was mostly hanging around talking with people about fishing and hunting all day.

The store had some issues with shoplifters from time to time. To counter this, the general manager hired a security guard: a big, broad-shouldered guy, an Air Force veteran who had served on the USAF Presidential Honor Guard. He was great at detecting thieves. Store policy was that all thieves were to be caught and charges pressed. If our security guy ever needed help, a bunch of us big teen-aged farm boys were always around to pile on and help him subdue a perp. Word of that got around – the Woolco will catch you and press charges. Shoplifting in our store dropped off pretty quickly.

Today, while stealing may be an easy way into some bucks in some places, it sure isn’t in our local Three Bears outlet. The Three Bears stores are something very Alaskan (although there is one outlet in Montana). You can buy a new handgun, shotgun, or rifle, traps and trapping supplies, hardware, and a bottle of hooch, all under one roof, as well as all your groceries and almost anything required to support a rural Alaska homestead. And in our local branch, the manager is a retired Marine who frequently is found standing in the store’s one entrance/exit.

Not long ago, while waiting for my wife to select some veggies, I was chatting with the manager and mentioned all the retail theft happening in the lower 48. Curious, I asked him what his policy was towards anyone walking out the door with a cart full of stolen goods.

He held up a huge, freckled fist. “Let them try,” he grinned.

That’s how we’ll stop this. Shoplifters are thieves. They should be apprehended, arrested, and prosecuted. Stupid laws like California’s Prop 47 must be repealed. Shoplifters should face serious consequences. Then, and only then, will California Walgreens outlets be able to remove the doors and padlocks from their merchandise counters.

Iowa’s own Chuck Grassley (R-IA) has introduced a bill that might move us in that direction. It will be interesting to see what happens with that.