The next generation of missiles – the hypersonic variety – made a brief appearance last week. The US is playing a bit of catch up with the Chinese and the Russians, who have had operational hypersonic weapons for some time now.

The Russians claim to have deployed their new Avangard missile capable of delivering a 2 megaton nuclear payload late last year, as reported here:

Russia’s first regiment of Avangard hypersonic missiles has been put into service, the defence ministry says.

The location was not given, although officials had earlier indicated they would be deployed in the Urals.

President Vladimir Putin has said the nuclear-capable missiles can travel more than 20 times the speed of sound and put Russia ahead of other nations.

They have a “glide system” that affords great maneuverability and could make them impossible to defend against.

As for the Chinese, they have deployed their new DF-17 after displaying it for the first time last fall in Beijing marking the 70th anniversary of Communist Party rule, as reported here:

The DF-17 is the first deployed hypersonic strike weapon for the PLA and can travel at speeds of more than 7,000 miles per hour — enough to outrun current U.S. anti-missile interceptors. Additionally, the missile is said to be maneuverable, a feature that allows it to further avoid electronic detection.

The state-run Xinhua News Agency described the DF-17 as a conventionally armed missile, a possible deception because Pentagon officials in the past told Congress that the missile was expected to be outfitted with either conventional or nuclear warheads.

Current U.S. missile interceptors, include the Navy’s ship-based SM-3 and the Army’s THAAD and Ground Based Interceptors (GBI), are said to be unable to counter the DF-17.

The 44 GBIs and related sensor systems are capable of stopping long-range missiles and their warheads that travel in non-maneuvering ways, but the high speeds of the DF-17 pose significant challenges for current defenses.

The US invested over $1 billion to accelerate the development of US hypersonic missiles, and an operational test was conducted last week in Hawaii (watch the launch video at this link):

The template for a new generation of Army and Navy weapons was put to the test in a late Thursday missile launch in Hawaii.

A prototype of the joint common hypersonic glide body (C-HGB) rode a modified Polaris A3 booster from a launch pad at the Pacific Missile Range Facility, Kauai. The successful test ended with the glide body landing at an undisclosed distance from the launch site, officials said.

The joint program is developing the common glide body that will house a conventional warhead and guidance system. This system will be the heart of the Army and Navy’s developing prompt global strike capability that will allow the U.S. to strike anywhere in the world within an hour.

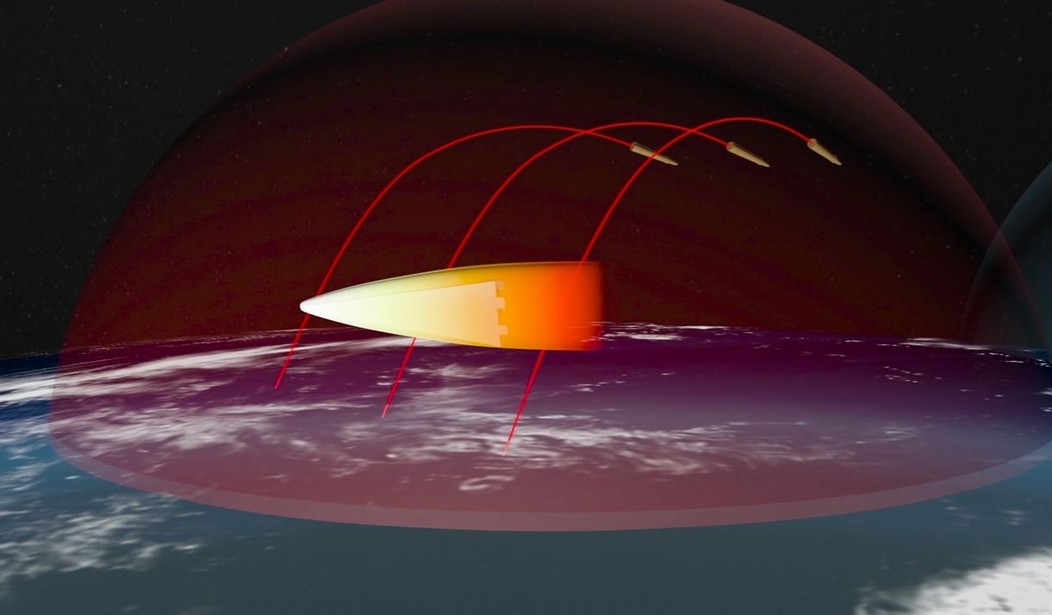

“Hypersonic weapons, capable of flying at speeds greater than five times the speed of sound (Mach 5), are highly maneuverable and operate at varying altitudes,” read a statement on the test. “This provides the warfighter with an ability to strike targets hundreds and even thousands of miles away, in a matter of minutes, to defeat a wide range of high-value targets.”

There are two variations of hypersonic weapons: glide vehicles and cruise missiles. Glide vehicles are similar to ballistic missiles in that they are rapidly boosted to high altitudes and then use momentum and control surfaces to “glide” through the atmosphere before hitting their targets. The cruise missiles use an advanced propulsion system for powered flight (although maneuverability during flight is the main engineering problem that must be overcome to ensure effectiveness).

The speed of these weapons adds a new calculus to the use of long-range missile systems, as the reaction times of defensive systems are greatly reduced and tracking the missiles in flight is a challenge. In addition, their potential use in a conflict complicates the decision-making process. One could argue that these weapons are more for intimidation of potential adversaries than for actual use – a sort of deterrent that reinforces a country’s diplomatic actions or implements “mutual vulnerability” – although their use in a “surprise attack” is within the realm of possibility. If deployed in large numbers, a first-launch could inflict near-instantaneous effects on a large number of primary and secondary targets at the beginning of a conflict. The speed at which these targets would be hit could change the escalation decision-making thought process, i.e., whether, how and when to respond to an attack.

At any rate, reaction times are greatly decreased, and the ability to detect pre-launch actions is complicated, as the weapons do not require easily detected launch preparations, complicating the tactical decision-making thought process of commanders in the field in particular.

The US is moving quickly to test and field operational hypersonic weapons systems. It is an arms race for all practical purposes.

The end.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member