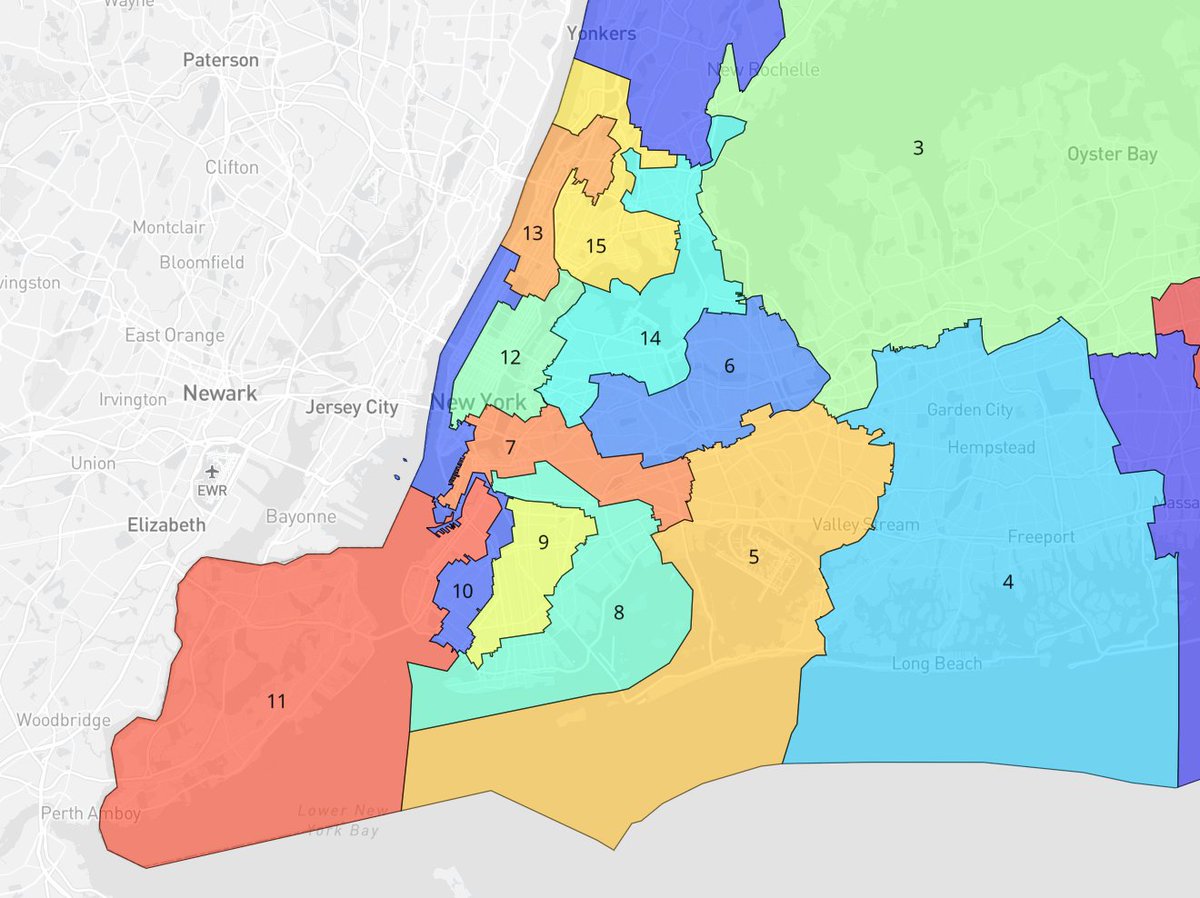

We are in the decennial season of Congressional redistricting, and we all know how this story goes. Democrat states are allowed free rein to draw lines pretty much as they wish. So, for instance, New York (which went for Biden 60-37 in 2020) has drawn a map that is 85-15 Democrat including one magnificent gerrymander to protect the interests of Fat Jerry Nadler in NY-10.

If you are a Republican state, then any attempt to trim away at Democrat seats or protect your current holdings is dragged into federal court and used as target practice by any leftist and Soros-funded group that wants to participate.

This is what is happening in Alabama.

Under the map created in 2011, Alabama has seven House seats. Six are held by Republicans and one by a Democrat. The one Democrat seat, AL-7, is also majority Black. None of the GOP seats are particularly vulnerable; an R+32 advantage is available to the weakest seat.

When the GOP tried to approve a new map with basically the same district lines, it was challenged in federal court, and a panel from the Northern District of Alabama concluded that Alabama was short one Black majority seat.

A panel of three federal judges threw out Alabama’s congressional map on Monday and ordered state lawmakers to draw a new one with two, rather than just one, districts that are likely to elect Black representatives.

The map that Alabama’s Republican-majority State Legislature adopted last fall drew one of the state’s seven congressional districts with a majority of Black voters. The court ruled that with Alabama’s Black population of 27 percent, the state must allot two districts with either Black majorities or “in which Black voters otherwise have an opportunity to elect a representative of their choice.”

“Black voters have less opportunity than other Alabamians to elect candidates of their choice to Congress,” the panel of judges wrote.

Singleton vs. Merrill by streiff on Scribd

Let me just stop here for a moment and throw out my opinion. Contrary to what the panel of judges thinks, I can’t think of anything being more racist in intent and more hostile to the vision of the Founders of our nation than the notion that black voters can only vote for black candidates or that black communities will always opt for black representation or that black candidate can only win in minority Black districts. If you want racial balkanization and de facto segregation, then I can’t conceive of a better way of going about it than by creating ethnic enclaves that politically fence in minority groups and ensure that they are represented by candidates running on a platform of racial identity or racialism, if not outright racism (looking at you, Maxine Waters).

A hired gun brought in by the plaintiffs drew several maps with two Black majority districts but, to do it, he had to demolish 2-3 districts that have been in existence since 1990, and he had to cherry-pick Black voters to move into his new district. You can see the various permutations at this link.

Alabama decided not to take this judicial overreach for the last word and, joined by fourteen other states (Arizona, Arkansas, Georgia, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Texas, Utah, and West Virginia) appealed to the Supreme Court.

“In a 234-page decision, just four days before Alabama’s candidate-filing deadline and mere months before absentee ballots will be sent to voters, a federal district court has enjoined Alabama from using its newly drawn congressional districts—districts Alabama created on a remarkably truncated schedule, through no fault of its own,” the AGs said. “In doing so, the district court injected confusion in the election cycle, penalized Alabama for diligently drawing new congressional districts on a tight timeline, and improperly held Alabama violated Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act by not using race as a predominate feature of its maps. This Court should grant the stay and end this Court-created injury.”

The legal equivalent of a Jack Russell terrier at Vox.com, Ian Milhiser, sees something more nefarious afoot. I can’t say that I disagree with him.

The lower court ordered the state legislature to redraw the map, relying on a provision of the Voting Rights Act banning racial gerrymanders. To reach that decision, the three judges spent 225 pages walking through the exceedingly complicated test announced in Thornburg v. Gingles (1986), which asks whether a state election law that imposes a disproportionate burden on racial minorities “interacts with social and historical conditions to cause an inequality in the opportunities enjoyed by [minority] and white voters to elect their preferred representatives.”

As I’ve written, the legal rule that the Court announced in Gingles — which governs many redistricting cases filed under the Voting Rights Act — is a mess. It advises courts to weigh at least nine different factors. And it would be reasonable for a state to ask the Supreme Court to come up with something less unwieldy to help lower courts sort through these sorts of cases. Alabama could have gone this route, and if it had proposed a reasonable modification to the Gingles test, it’s possible that such a modification could have helped them defend their maps.

But Alabama does nothing of the sort in the Merrill case. Instead, it proposes a new rule that, if adopted by the Supreme Court, could effectively make it impossible to challenge a racial gerrymander in federal court.

At one point, for example, Alabama quotes favorably from a 1994 opinion by Justice Clarence Thomas, which was joined only by one other justice, and which suggests that no voting rights violation occurs even if a state gerrymanders its districts to make it impossible for racial minorities to elect their preferred candidate. Under this theory, “minorities unable to control elected posts would not be considered essentially without a vote; rather, a vote duly cast and counted would be deemed just as ‘effective’ as any other.”

The state’s primary argument, meanwhile, would trap voting rights plaintiffs in a kind of Catch-22.

Alabama Response to Singleton vs. Merrill by streiff on Scribd

The Catch-22 Milhiser refers to is that Alabama argues that it is illegal to use race as a primary factor in redistricting, but to get two Black majority districts, the only way you can do that is by using race as the only characteristic.

Well-established in the court below, no race-neutral map drawer would draw that map. In a sample of more than two million race-neutral maps generated by 1Plaintiffs’ own experts, not even one contained two majority-black districts. There is no better evidence that the first precondition for a vote dilution claim has not been met here. See Thornburg v. Gingles, 478 U.S. 30, 50-51 (1986). A second majority black district that can be drawn only by initially subverting race-neutral redistricting criteria to a “non-negotiable” racial target is not a “reasonably configured” district. Cooper v. Harris, 137 S. Ct. 1455, 1470 (2017). Accordingly, no invocation of the VRA can justify, much less require, the race-based redraw of Alabama’s race-neutral map.

I am neither a lawyer nor a necromancer, but I can’t help but feel that Milhiser accurately senses the way the wind is blowing here. Not only do you have the state’s defense that the districts have been in place for 30 years, that they got data late, and they are acting in good faith, I get the sensing that the Supreme Court is trying to pull back from some of the positions it took in the past that embroiled it in hot-button issues. For instance, last term, both Roe v. Wade (Supreme Court Humiliates Biden, Refuses to Stop Texas Heartbeat Law, and Gorsuch and the Wise Latina Have a Public Spat) and gun control (Supreme Court Conservatives Maul New York’s Restrictive Concealed Carry Law in First Major Second Amendment Case in a Decade) was manhandled in oral arguments. Of course, you can’t tell how a case is going to turn out by the arguments, but the combativeness of the conservative questions indicated that the majority was tired of seeing the same issue over and over.

Ever since the Supreme Court got the courts out of the redistricting business in Shelby County v. Holder, it has raised the bar for federal judicial interference in a state prerogative. In Rucho vs. Common Cause, the Supreme Court held that blatant partisan gerrymanders were not reviewable by federal courts. It doesn’t take a legal genius to see that a court skeptical about the idea of racial quotas (for the Roberts-doubters, I’d point you toward his record on affirmative action and various voting rights grifts as well as his opinions acknowledging that no matter how virtuous the intent, the government can’t make decisions based primarily on race) that has already done away with “pre-clearance” isn’t very far away from saying that unless you can prove that diluting minority vote was the intent of drawing a district, the state’s version of the map prevails.

The potential irony of this decision is just too much to contemplate. Activist groups suing Alabama over a 30-year-old district map could potentially destroy the racial gerrymandering grift for the entire country.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member