[Originally posted in 2015 and recycled because the subject came up elsewhere.]

Most everyone, outside the Obama administration, its supporters, the liberal arts faculty in most major universities, and a disturbing number of high school history teachers, is familiar with Washington’s crossing of the Delaware on the night of December 25-26, 1776, and the stunning surprise victory that ensued in the streets of Trenton, New Jersey. What is often lost in the telling of the narrative is the tactical sophistication that George Washington was developing by the winter of 1776-77 and a little known battle, one which I think shows Washington at his finest, that took place on January 2, 1777. This battle, Second Trenton or the Battle of Assunpink Creek, preserved the initiative gained at First Trenton and set up the victory at the Battle of Princeton (January 3, 1777) which resulted in the Forage War and the forced evacuation of New Jersey by British forces during the winter of 1777.

First Trenton

A grave disservice is done to Washington and to the Continental army and Pennsylvania and New Jersey militia in the traditional telling of this story. There is quite a bit of evidence that Washington planned the crossing of the Delaware, in broad terms, during the retreat through New Jersey. As the Continental army retreated across the Delaware, Washington ordered the Delaware river scoured for miles for watercraft of all sizes to be collected from the Jersey shore and concentrated at spots near his winter quarters in Pennsylvania. A traditional approach would simply have burned or destroyed the craft to prevent the British from using them in pursuit or for their own crossing in the spring. The fact that Washington had the boats confiscated ensured that he had the ability to cross the Delaware while the British were effectively marooned on the far side of the river.

In popular imagination, Washington pounced on arrogant and drunk Hessians the morning after Christmas, routing them. The actual facts tell a different tale. Though Washington held militia in general low regard when it came to holding their place in line of battle:

To place any dependence upon militia, is, assuredly, resting upon a broken staff. Men just dragged from the tender scenes of domestic life – unaccustomed to the din of arms – totally unacquainted with every kind of military skill, which being followed by a want of confidence in themselves when opposed to troops regularly trained, disciplined, and appointed, superior in knowledge, and superior in arms, makes them timid and ready to fly from their own shadows.

But he recognized there were some things militia could do very well. They could scout and they could fight delaying actions where they were not expected to slug it out, bayonet to bayonet, with British regulars. Using Pennsylvania and New Jersey militia built around a core force of the 1st Pennsylvania Regiment (aka the Pennsylvania Rifle Regiment, commanded by Colonel Edward Hand), Washington created a veritable hell on earth for British and Hessian forces billeted in south New Jersey. By the time Washington crossed the Delaware, any messenger required the escort of a company of infantry if he were to be able to make it to his destination. Food was in short supply because entire battalions were required to forage for food and to provide security for the foragers. This was to be repeated during the Forage War that drove the British from New Jersey. On that morning after Christmas, 1776, the Hessians at Trenton were sluggish but it wasn’t from drink. They were exhausted. Many in the regiment had not been out of uniform for days, they were called out several times a night to react to raids on outposts, when not on guard in Trenton they were marching about the countryside foraging for food and escorting messengers.

Trenton was a gamble on Washington’s part but it was a cold blooded and calculated one where the ground work had been cleverly laid over a period of weeks.

Second Trenton: Prelude

After winning at First Trenton, Washington, rather than waiting around for a British counterattack, retreated back across the Delaware on December 27, planned his next moves. The enlistments of most of Washington’s army expired at midnight on December 31. It was no secret that most of the men with expiring enlistments felt that they had done their duty and now it was time for someone else to step up. He also knew that the numbers of British and Hessian forces in New Jersey would grow during the spring and unless he did something to change the strategic situation the war would end in the next campaign. Because the British didn’t respond to his attack on Trenton, he decided to strike again.

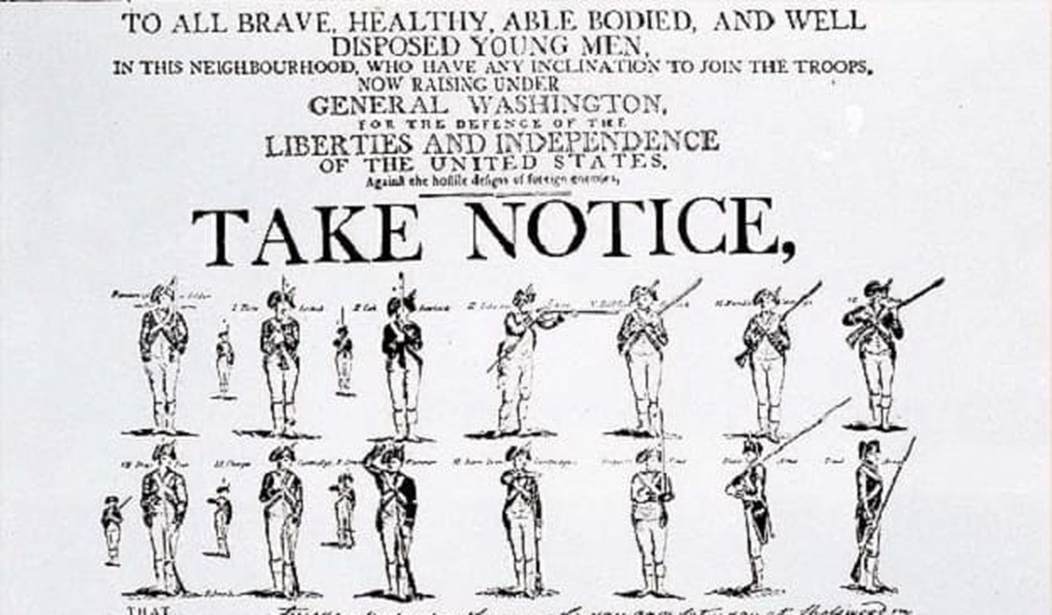

Washington was nothing if not an optimist. On December 28, with over a third of his army incapacitated by disease and most of it looking forward to being a civilian again in three days, Washington issued a call to the New Jersey militia to harass British forces in southern New Jersey and announced to them that he would shortly be on the attack:

I am about to enter the Jersies with a considerable force immediately.

Then Washington turned his attention to making sure he had an army in three days time. From the epic Washington’s Crossing by David Hackett Fischer:

He mustered the New England regiments and begged them to serve another six weeks. A sergeant remembered that the general “personally addressed us…told us that our services were greatly needed, and that we could od more for our country than we ever could at any future date, and in the most affectionate manner entreated us to stay.” Then the regimental commanders asked all who would stay to step forward. “The drums beat for volunteers,” one remembered, “but not a man turned out.” One explained that his comrades were “worn down with fatigue an privations, had their hearts fixed on home and comforts of the domestic circle.” The men watched as Washington “wheeled his horse about, rode in front of the regiment,” and spoke to them again. Long afterward, a sergeant still remembered his words.

“My brave fellows,” Washington began, “you have done all I asked you to do, and more than could be reasonably expected; but your country is at stake, your wives, your houses, and all that you hold dear. You have worn yourselves out with the fatigues and hardships, but we do not know how to spare you. If you will consent to stay one month longer; you will render that service to the cause of liberty, and to your country, which you probably can never do under any other circumstances.”

The drums rolled again. The sergeant recalled that “the soldiers felt the force of the appeal” and began to talk among themselves. One said, “I will remain if you will.” Another said, “We cannot go home under such circumstances.” A few men stepped forward, then several others, then many more and “their example was [followed] by nearly all who were fit for duty in the regiment, amounting to about two hundred volunteers.” These were veterans who understood what they were being asked to do. They knew well what the cost might be. One of them remembered later that nearly half the men who stepped forward would be killed in the fighting or dead of disease “soon after.”

Second Trenton: Arrival in Trenton

Almost immediately after reenlisting these soldiers were again in boats, crossing the ice-choked Delaware, and marching towards Trenton. The arrived on January 1 and took up positions on high ground behind Assupink Creek, south and east of Trenton.

The British Army in Princeton was quickly apprised of Washington’s arrival in New Jersey and most of the garrison, some 5,000 men under General Charles Cornwallis marched to attack. Washington had a small advantage in numbers, probably outnumbering the British by about 1,000 and having 40 field pieces to Cornwallis’s 28. This is deceptive as by any qualitative measure the British Army was superior.

Second Trenton: Delaying Action

It is only 11 miles from Princeton to Trenton. Cornwallis was on the road early on January 2. He expected to arrive at Trenton in about three hours, well before noon, and settle Washington’s hash soon afterwards.

Washington had no intention of fighting the British on their own terms and his move to Trenton was designed merely to draw the British out of Princeton. He established what would today be called a covering force of militia and Pennsylvania riflemen under the command of French soldier of fortune, Matthias Alexis Roche de Fermoy. This was not an inspired choice. De Fermoy lost his nerve, got blind staggering drunk, though not too drunk to ride a fast horse, and decamped from his command. Into the breach stepped the colonel of the 1st Pennsylvania, Edward Hand, a 33-year old physician and part of the Scots-Irish ascendancy that was rapidly replacing Quakers as the political class of Pennsylvania. Hand had been with the 1st Pennsylvania on Long Island and had learned a lot about soldiering the hard way: by getting shot at by professionals.

He fought a series of brilliant delaying actions — most prominent were Five Mile Run, Little Shabbakunk Creek, and Stockton Hollow — that slowed the British advance to a crawl. Rather than an easy four hour march, the approach turned into an ordeal of about twelve hours that left the British bloodied, Fischer estimates they lost about 400 men, nearly 10% of their strength, and they arrived at Washington’s positions with less than a half hour of daylight.

Second Trenton: The Battle

Washington had chosen his position with a canniness that maximized his army’s preference from fighting from a strong defensive position (Washington constantly tried to recreate Bunker Hill in his battles, in fact, the entire Long Island campaign is really one attempt after another to lure the British into a headlong attack. Second Trenton is as close as he ever came to doing this). He was entrenched on high ground. Assupink Creek was running high and could only be crossed at a few fords and a single bridge. He also minimized the ability of his army to run at the sight of British bayonets, an unfortunate trait the Continental Army possessed until the hard Valley Forge winter under von Steuben and demonstrated at its coming of age battle at Monmouth. While Assupink Creek could only be crossed in a very few places by the British, the Delaware River, behind the Continental lines, couldn’t be crossed at all. If Washington’s line didn’t hold then every man was going to be killed or imprisoned on a prison hulk in New York harbor.

Pressing to finish Washington before dark, the British did a rudimentary reconnaissance and attacked. Cornwallis made an attempt to flank Washington by sending Hessian Jaegers and Britiish Light Infantry against the Continental outposts and the lower fords on the Assupink. They were stopped in their tracks. Then Hessian grenadiers were sent in column to attack over the lone bridge. Continental musket and artillery soon stacked the bridge with corpses. Another attack was made on the bridge, this one by British infantry. Washington’s chief of artillery, a rotund, bespectacled Boston bookseller called Henry Knox, massed his artillery and drove off the attackers.

By now it was dark, as temperatures fell into the teens, British and German pickets were deployed to keep watch and to fight off American patrols. Cornwallis called a council of war. Should, he asked his commanders, they continue the attack in the dark or wait until the next morning. His Quartermaster General (a much different position in those days than today) and Eton schoolmate, Sir William Erskine counselled an immediate attack.

“My Lord, if you trust those people tonight you will see nothing of them in the morning.”

Corwallis demurred. His army was tired. He was on unfamiliar ground. He had been repulsed by the Continentals three times. He was keenly aware of the political impact of the Hessian surrender on December 26 and didn’t want to give Washington another victory.

We’ve go the Old Fox safe now. We’ll go over and bag him in the morning.”

That night, behind a mask of blazing bonfires, rags were tied on wagon wheels , the wheels of artillery caissons, and horse’s hooves and the Continental Army silently slipped around the British flank, and fell on the British supply depot at Princeton the next day.

In short order, what had been a decisive British campaign in New York and New Jersey in the summer of 1776 was nullified. Washington won three victories over the British in a period seven days, moved his winter quarters to a position to threaten New York City in the spring, and unleashed the New Jersey militia on a dispersed ring of British camps that forced the evacuation of the colony of New Jersey.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member