I feel like such a failure. We're 25 Supreme Court decisions into the 2024 term...and I've gotten us through 11 of them. In my defense, there have been quite a few other court cases (some even involving input from SCOTUS) hitting the docket fast and furious, and it's been rather like the proverbial drinking-from-a-firehose on the litigation front, but enough with the excuses.

We've got four more cases from February to digest. Two of them were 9-0 decisions, while one was a 7-2 split and the other a 5-3 split (with Justice Gorsuch not participating). All four of these were procedural rulings, some more complex than others.

So, let's get to it:

February 2025 Decisions - Part 1

Date: February 25, 2025

Author: Roberts

Split: 7-2

Dissent: Jackson, Sotomayor

Appeal From: 4th Circuit

Drivers whose licenses were suspended under a Virginia statute for failure to pay court fines sued the Commissioner of the Virginia Department of Motor Vehicles under 42 U. S. C. §1983, challenging the statute as unconstitutional. The District Court granted a preliminary injunction prohibiting the Commissioner from enforcing the statute. Before trial, the Virginia General Assembly repealed the statute and required reinstatement of licenses suspended under the law. The parties then agreed to dismiss the pending case as moot.

Section 1988(b) allows an award of attorney’s fees to “prevailing parties” under §1983. The District Court declined to award attorney’s fees to the drivers under that section on the ground that parties who obtain a preliminary injunction do not qualify as “prevailing part[ies].” A Fourth Circuit panel affirmed, but the Fourth Circuit reversed en banc. The en banc court held that some preliminary injunctions can provide lasting, merits-based relief and qualify plaintiffs as prevailing parties, even if the case becomes moot before final judgment.

- Whether a party must obtain a ruling that conclusively decides the merits in its favor, as

opposed to merely predicting a likelihood of later success, to prevail on the merits under 42 U.S.C. § 1988.

Whether a party must obtain an enduring change in the parties' legal relationship from a judicial act, as opposed to a non-judicial event that moots the case, to prevail under 42 U.S.C. § 1988.

Holding: Reversed and remanded.

The plaintiff drivers here—who gained only preliminary injunctive relief before this action became moot—do not qualify as “prevailing part[ies]” eligible for attorney’s fees under §1988(b) because no court conclusively resolved their claims by granting enduring judicial relief on the merits that materially altered the legal relationship between the parties

Skinny: To collect attorney fees under the statute in question, you have to score an outright win — not just a predicted win.

Date: February 25, 2025

Author: Sotomayor

Split: 5-3

Dissent: Thomas, Alito; Barrett - partially

Appeal From: Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals

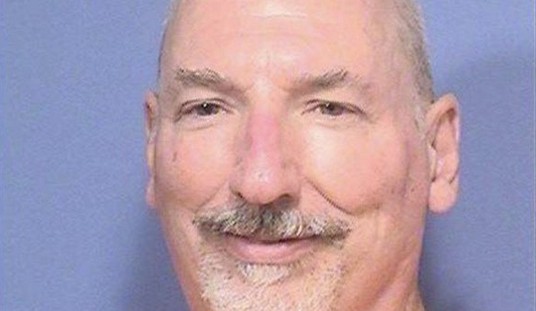

In 1997, Justin Sneed beat Barry Van Treese to death with a baseball bat at an Oklahoma hotel owned by Van Treese and managed by petitioner Richard Glossip. Glossip initially made inconsistent statements to the police about Sneed’s role in the murder, but he ultimately told police that Sneed admitted to killing Van Treese. Sneed later claimed Glossip had asked him to murder Van Treese because, among other things, Glossip had wanted to steal Van Treese’s money. Glossip maintained his innocence and refused a plea deal that would have had him avoid the death penalty in return for testifying against Sneed. Sneed then testified against Glossip at trial in exchange for avoiding the death penalty, and Sneed’s testimony was the only direct evidence connecting Glossip to the murder. The jury convicted Glossip and sentenced him to death. The Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals (OCCA) overturned that conviction because the defense had been ineffective in challenging Sneed’s testimony and the remainder of the evidence only weakly corroborated Sneed’s account. At the retrial, Sneed provided inconsistent testimony on potential motives for Glossip’s murder. Sneed also denied that he had been prescribed lithium or seen a psychiatrist. After the defense established (through the State’s medical examiner) that Van Treese had been attacked with a knife as well as a bat, Sneed testified that he had repeatedly tried to stab Van Treese in the chest with a pocket knife. But Sneed had previously denied stabbing Van Treese both when questioned by the police as well as at Glossip’s first trial. Glossip moved for a mistrial based on the prosecution’s failure to notify the defense about Sneed’s change in testimony, which the trial court denied after the prosecution disclaimed any knowledge about the change. Glossip was again convicted and sentenced to death, and a closely divided OCCA affirmed, holding that circumstantial evidence suggesting Glossip had mismanaged the hotel, combined with Glossip’s concession that he had been dishonest in his initial statements after the murder, sufficiently corroborated Sneed’s testimony that he killed Van Treese at Glossip’s direction.

Glossip subsequently filed several unsuccessful habeas petitions. Concerns over the integrity of his conviction led a bipartisan group of Oklahoma legislators to commission an independent investigation by a law firm, Reed Smith. In June 2022, Reed Smith reported “grave doubt” about Glossip’s conviction, citing factors such as the prosecution’s deliberate destruction of key evidence and the false portrayal of Justin Sneed as a non-violent “puppet.” The State then disclosed seven boxes of previously withheld documents, including letters suggesting Sneed had considered recanting and a note from prosecutor Connie Smothermon to Sneed’s lawyer noting they should “get to” Sneed to discuss his problematic testimony about a knife found in Van Treese’s room. Glossip filed for post-conviction relief based on this evidence and evidence revealed by Reed Smith. Glossip also argued that, during his second trial, Smothermon had interfered with Sneed’s testimony about the knife in violation of the rule of sequestration, which prohibits witnesses from hearing each other’s testimony. Oklahoma waived any procedural defenses to Glossip’s claims, and asked the OCCA to deny the claims on their merits. The OCCA denied Glossip’s claims as procedurally barred and meritless.

The State then discovered additional documents revealing that Sneed had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and prescribed lithium, contradicting his trial testimony. The attorney general determined that Smothermon had knowingly elicited false testimony from Sneed and failed to correct it, violating Napue v. Illinois, 360 U. S. 264, which held that prosecutors have a constitutional obligation to correct false testimony. Glossip filed a successive petition for post-conviction relief, which the attorney general supported, conceding multiple errors that warranted a new trial. The OCCA denied the unopposed petition without a hearing, holding that Glossip’s claims were procedurally barred under Oklahoma’s Post-Conviction Procedures Act (PCPA), and further that the State’s concession was not “based in law or fact” because it did not create a Napue error. This Court stayed Glossip’s execution and granted certiorari.

1. a. Whether the State's suppression of the key prosecution witness's admission he was under the care of a psychiatrist and failure to correct that witness's false testimony about that care and related diagnosis violate the due process of law.

b. Whether the entirety of the suppressed evidence must be considered when assessing the materiality of Brady and Napue claims.

2. Whether due process of law requires reversal, where a capital conviction is so infected with errors that the State no longer seeks to defend it.

Holding: Reversed and remanded.

The court has jurisdiction to review the judgment of the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals; the prosecution violated its constitutional obligation to correct false testimony under Napue v. Illinois.

Skinny: To convict someone of a crime (particularly where the death penalty is on the line), lower courts need to dot "i's" and cross "t's" — and if the prosecution screwed up and allowed in false testimony, they have an obligation to correct it.

Added Note: This one is 5-3 because Justice Gorsuch did not participate in the case. Justice Barrett concurred in part and dissented in part, largely because while she agreed with the court's analysis overall, she would not have ordered the conviction set aside but rather would have remanded for further proceedings consistent with the court's guidance.

Waetzig v. Halliburton Energy Services, Inc.

Date: February 26, 2025

Author: Alito

Split: 9-0

Dissent: N/A

Appeal From: 10th Circuit

Gary Waetzig filed a federal age-discrimination lawsuit against his former employer Halliburton Energy Services, Inc. He later submitted his claims for arbitration, and voluntarily dismissed his federal lawsuit without prejudice under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 41(a). After losing at arbitration, he asked the District Court to reopen his dismissed lawsuit and vacate the arbitration award, asserting Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 60(b) as the basis for reopening the suit. Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 60(b) permits relief from a “final judgment, order, or proceeding.” The District Court reopened the case, finding that a voluntary dismissal without prejudice counts as a “final proceeding” and that Waetzig made a mistake when he dismissed his case rather than seeking a stay. The District Court separately granted Waetzig’s motion to vacate the arbitration award. The Tenth Circuit reversed.

Whether a Rule 41 voluntary dismissal without prejudice is a "final judgment, order, or proceeding" under Rule 60(b).

Holding: Reversed and remanded.

A case voluntarily dismissed without prejudice under Rule 41(a) counts as a “final proceeding” under Rule 60(b).

Skinny: This is a procedural ruling only — i.e., the district court was right to allow Waetzig's case (which he voluntarily dismissed without prejudice) to be reopened. Whether he is ultimately entitled to relief from the arbitration award remains to be seen.

Dewberry Group, Inc. v. Dewberry Engineers, Inc.

Date: February 26, 2025

Author: Kagan

Split: 9-0

Dissent: N/A

Appeal From: 4th Circuit

The federal Lanham Act provides for a prevailing plaintiff to recover the “defendant’s profits” deriving from improper use of a mark. 15 U. S. C. §1117(a). Dewberry Engineers successfully sued Dewberry Group—a competitor real-estate development company—for trademark infringement under the Lanham Act. Dewberry Group provides services needed to generate rental income from properties owned by separately incorporated affiliates. That income goes on the affiliates’ books; Dewberry Group receives only agreed-upon fees. And those fees are apparently set at less than market rates—the Group has operated at a loss for decades, surviving only through cash infusions by John Dewberry, who owns both the Group and the affiliates. To reflect that “economic reality,” the District Court treated Dewberry Group and its affiliates “as a single corporate entity” for purposes of calculating a profits award. The District Court thus totaled the affiliates’ real-estate profits from the years Dewberry Group infringed, producing an award of nearly $43 million. A divided Court of Appeals panel affirmed that award.

Whether an award of the "defendant's profits" under the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1117 (a), can include an order for the defendant to disgorge the distinct profits of legally separate non-party corporate affiliates.

Holding: Vacated and remanded.

In awarding the “defendant’s profits” to the prevailing plaintiff in a trademark infringement suit under the Lanham Act, §1117(a), a court can award only profits ascribable to the “defendant” itself. And the term “defendant” bears its usual legal meaning: the party against whom relief or recovery is sought—here, Dewberry Group. The Engineers chose not to add the Group’s affiliates as defendants. Accordingly, the affiliates’ profits are not the (statutorily disgorgable) “defendant’s profits” as ordinarily understood.

Skinny: You have to sue the actual legal entities whose profits you wish to recover.

Added Note: Justice Sotomayor filed a concurring opinion — she agreed with the court's decision in this case but pointed out that on remand, the lower court could (and hinted it probably should) reopen the record to determine if the Dewberry Group's affiliates truly were properly kept at arm's length and as distinct legal entities, such that their profits couldn't be considered/available for recovery.

You can check out prior installments of The Skinny on SCOTUS series here.