On Monday, the Supreme Court, in a 9-0 decision in Caniglia v. Strom, overruled the First Circuit Court of Appeals which had held a plaintiff’s Fourth Amendment rights had not been violated in a civil case involving the police entering his house without a warrant to seize lawfully owned and possessed firearms inside.

I wrote about this case originally over on Substack, covering the facts in detail. Simply stated, a domestic dispute between Mr. Caniglia and his wife led to a visit by the police. The matter was resolved with a “voluntary” psychiatric examination of Mr. Caniglia, who was transported by the police to the hospital. While there, and supposedly at the request of Mrs. Caniglia, the police entered the house and removed two handguns. For purposes of the case, the Court accepted as true that the police had misled Mrs. Caniglia with regard to their intentions, and that her consent and assistance in seizing the firearms was not voluntary.

Mr. Caniglia brought a civil action against the local officials claiming they violated his Fourth Amendment rights by searching his house without a warrant and seizing his lawfully owned and possessed firearms. He was never charged with any crime, the police were not investigating a crime when they persuaded him to undergo a psychiatric evaluation — they feared he was suicidal — and the search for and seizure of the firearms was not in connection with a search for evidence of criminal activity.

Relying upon the “community caretaker” doctrine, involving police actions separate from their duty to investigate criminal activity, the lower courts found no “unreasonable” search in violation of the Fourth Amendment, notwithstanding the fact that the search of the home was done without a warrant and without probable cause regarding a crime.

This doctrine has arisen over the course of several decades and began with the 1973 Supreme Court case of Cady v. Dombrowski. That case involved the search by police in Wisconsin of the trunk of a Chicago police officer’s personal vehicle based on a belief that the off-duty officer’s police weapon might be in the trunk of the car. The car was parked in a mechanic’s garage after it had been involved in an accident. Cady was drunk at the time of the accident, lapsed into a coma at the hospital, and could not answer questions after his car was towed. The Wisconsin police searched his vehicle because they believed Chicago PD policy required Cady to have it with him at all times.

But the search of the trunk uncovered evidence of a murder committed by Cady the day before the accident. The Supreme Court upheld the warrantless search of the trunk against a Fourth Amendment challenge because exceptions to the warrant requirement already exist for automobiles, and also because the purpose of searching Cady’s vehicle was non-investigatory. It was done to safeguard the community against the possibility that others might break into the car and discover the firearm.

In Caniglia, the First Circuit — for the first time — extended the “community caretaking function” to include the warrantless search of a residence, upholding the lower court judgment in favor of the police in the civil action brought by Caniglia for an unlawful search of his house.

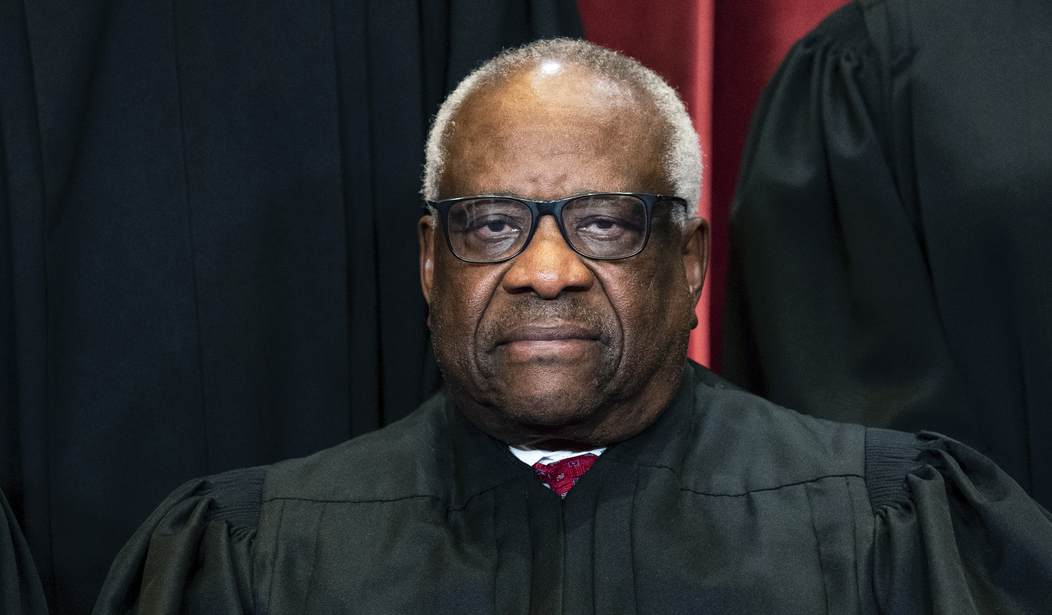

Justice Thomas made short work of the outcome of the case, writing an opinion that, outside of the facts, covers only two pages.

Cady’s unmistakable distinction between vehicles and homes also places into proper context its reference to “community caretaking.” This quote comes from a portion of the opinion explaining that the “frequency with which . . . vehicle[s] can become disabled or involved in . . . accident[s] on public highways” often requires police to perform noncriminal “community caretaking functions,” such as providing aid to motorists. 413 U. S., at 441. But, this recognition that police officers perform many civic tasks in modern society was just that—a recognition that these tasks exist, and not an open-ended license to perform them anywhere.

* * *

What is reasonable for vehicles is different from what is reasonable for homes. Cady acknowledged as much, and this Court has repeatedly “declined to expand the scope of . . . exceptions to the warrant requirement to permit warrantless entry into the home….” We thus vacate the judgment below and remand for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

When I wrote about this case earlier, I stated that I could not envision any circumstance under which the Court took up this case to affirm the First Circuit’s decision.

To have done so would have opened up a “Pandora’s Box” of warrantless searches of homes outside the extremely narrow context that has been allowed by the Court so far.

The First Circuit’s opinion noted that it had never before applied the “community caretaker doctrine” to searches of a home, but also noted that several other federal courts of appeal had adopted the “community caretaker” doctrine and allowed such searches on that premise.

Today’s decision puts a stop to all such searches. The allowable grounds for making a warrantless entry into a home remain limited as defined by previous Supreme Court decisions, and the “community caretaker doctrine” is not recognized as an extension of such permissible warrantless searches.

The alternative to this outcome would have been potentially enormous because it would have set off a frenzy of “gun-grabbing” conduct by law enforcement officials in states and localities where there is overt hostility to the issue of private gun ownership. Only the creativity of the police officials would have limited the “community caretaker” justifications they would have employed to give them grounds to enter a private residence without a warrant in order to seize lawfully owned firearms located inside. It would have made private gun ownership subject to whatever articulation of “reasonableness” could be conjured up after the fact by the seizing authorities.

It would have written the Second Amendment phrase “the right of the people to keep and bear arms” in such a way as to make it conditional on the subjective judgment of government officials that allowing you to do so was not unreasonable.

There is an interesting factual anomaly here that I noted in my earlier article.

Among the three judges on the panel of the First Circuit Appeals Court that extended the doctrine to cover warrantless searches of homes was retired Supreme Court Justice David Souter.

You could look at this as the Supreme Court unanimously reversing a former Supreme Court Justice.

I’m not sure that has ever happened before.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member