It has always been an idiotic idea — one that puts a premium on “convenience” over all else.

Absentee ballots have played a role in elections for as long as I can remember, but only where they were dictated by necessity.

While the COVID-19 pandemic did lead most states to look for alternatives to having voters congregate in public polling places as the primary method for voting, the Democrats were pushing for expanded absentee and “vote-by-mail” (VBM) as an election strategy long before COVID-19. Some one-party Democrat states — Hawaii and Oregon come to mind — were already in the process of moving to all VBM voting; the Democrats in most other states were pushing for greater eligibility for use of absentee ballots across the country.

There were two primary motivating factors for seeking to dramatically increase mail-in ballots. First, the parties could track the names of voters who had mailed in ballots in advance of election day. That meant efforts to get their remaining registered voters to the polls on election day could focus on those who had not yet voted thereby making those efforts more efficient and more effective.

Second, combining vote-by-mail with “ballot harvesting” put party operatives in the business of actually delivering ballots to be counted. It put party operatives in touch with registered voters in a situation where the party operative could sit with the registered voter while they filled out their ballots. The “privacy” of the polling booth was lost, and greater party “peer pressure” could be used to ensure straight-ticket voting.

The impact of these practices in the 2018 midterm elections in California played a large role in the Democrat efforts to expand the practice to other states — especially anticipated battleground states in the Presidential election. The Democrats were able to “flip” on very narrow margins long-time GOP held House seats in Southern California using ballot harvesting, thereby validating the effectiveness of the practice.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, state legislatures took pending efforts by Democrat interest groups for expanded absentee voting and recast them as state-wide VBM authorizations. Without giving much consideration to the practical problems of implementing VBM on such a massive scale, the states saw it as a necessary step to take as a public health matter. “Signature matching” verifications similar to those used for existing absentee ballot voting were adopted as a basis to prevent fraudulent voting in the name of other people — dead or alive. But, again, these processes were not well thought out in terms of the mechanics and practical limitations of what could — or would — be done in the very short window of time that millions of mailed-in ballots would need to be counted.

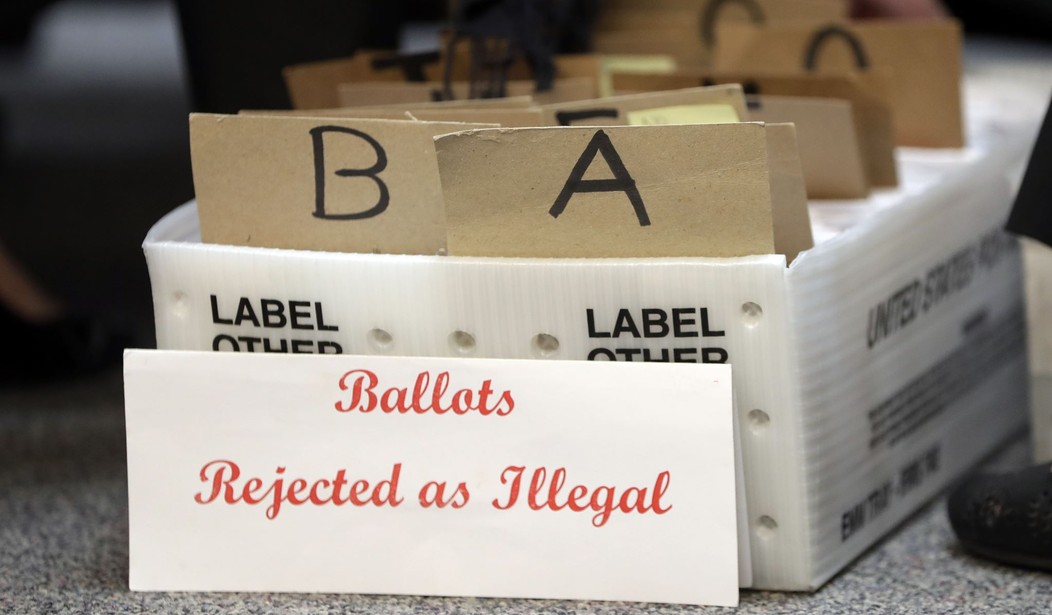

Further, no sooner had these VBM statutes passed than Democrat interest groups and state Democrat party organizations began filing lawsuits challenging the signature matching requirements on the basis that it would be a violation of the right to vote for untrained election workers to reject VBM ballots based on their “opinion” that signatures on the ballot and in the voter’s “file” — in whatever form that may be — did not match. In response to some of these actions — including in Georgia — state officials, including elected GOP officials, opted to reach settlements in advance of upcoming elections that imposed cumbersome bureaucratic processes on any decision to reject a ballot based on mismatched signatures. Georgia’s process — agreed to in order to settle a lawsuit brought by the Democrat Party of Georgia, represented by Marc Elias and the Perkins Coie firm — requires the election workers who seek to reject a ballot to stop the process, solicit the involvement of two other election workers on the issue, with all three of them taking the time to look at the voter’s signatures in an “eFile”, and then make a determination as to whether the signatures match. If all three agree the signature does not match, they write “Rejected” on the envelope, provide the information required by the statute on the envelope as to why, and the names and signatures of the three election officials who made the decision. That envelope then goes to another election official who must take certain steps set forth in the settlement agreement to contact that voter, advise him or her that the ballot has been rejected and why, and then explain their options for “curing” the defect in their ballot.

The alternative is just to count the ballot and move on.

Which do you suppose happened more often in the frantic 24 hours after the polls closed in Georgia on Election Day while the entire country waited for the VBM ballots to be counted?

Several federal court actions managed to land before district court judges appointed by Pres. Obama ended with these kinds of outcomes in the sense that state election officials were ordered to make modifications to their practices in making signature matches due to the extraordinary volume of VBM ballots that were being anticipated. In many cases, the orders from those district judges were overturned on appeal. But not all of them. In Georgia, as noted, the elected GOP officials in the state agreed to settle the case there and election day went forward on the terms as set forth in that settlement agreement. Now you have the State GOP establishment defending itself in a situation where no one can say how many mismatched signatures there were — or if a meaningful effort was even made by election workers to actually match signatures on VBM ballots to the signatures in voters’ “eFiles” as required. The Georgia Secretary of State says the procedures were followed, but has resisted all suggestions for a validation process that would show that to be the case.

A statewide hand recount is underway, but that recount won’t test the effectiveness of the signature matching verification process that was supposed to guard against the introduction of fraudulent ballots.

What would do so is a statistically significant sampling of VBM ballots from each county by a third-party group which then does an independent “signature matching” analysis. Then compare the rejection rate of that neutral process against the rejection rate of each county’s election workers to determine if some counties were more “lenient” in allowing invalid VBM ballots to be counted.

Each invalid ballot that was counted cancels out a valid ballot cast for the opposing candidate. It cancels out the right to vote of another voter who expressed a different choice. The voter whose ballot was canceled out by an invalid ballot is the victim of this process no less than a voter whose ballot is wrongfully rejected because of an inaccurate signature match decision.

But all the pontificating about guaranteeing the “right to vote” always fails to acknowledge the harm done by allowing invalid votes to be cast and counted.

Most legislation that I’ve reviewed which expanded VBM based on COVID-19 concerns did so for only the 2020 election cycle, and not as a permanent expansion of absentee ballot eligibility. That is the direction that Democrats want to go.

GOP controlled legislatures must step up and put a stop to this. In-person voting on election day at polling places must be the method by which nearly all votes are cast. Election integrity — NOT VOTER CONVENIENCE — needs to drive the debate and the decision-making.

Nothing can be done for now in those states where Democrats control the state legislature, or state government is divided. But that doesn’t mean the GOP should drink the hemlock in the states they do control.

Voter marked paper ballots, in a controlled environment, delivered directly to election officials without the participation of partisan actors in the process, is the most secure election process. It can be inconvenient, and that might influence voter participation.

But “best practices” — not most convenient practices — must be the determinative factor for something as crucial as the method by which this country picks its political leaders.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member