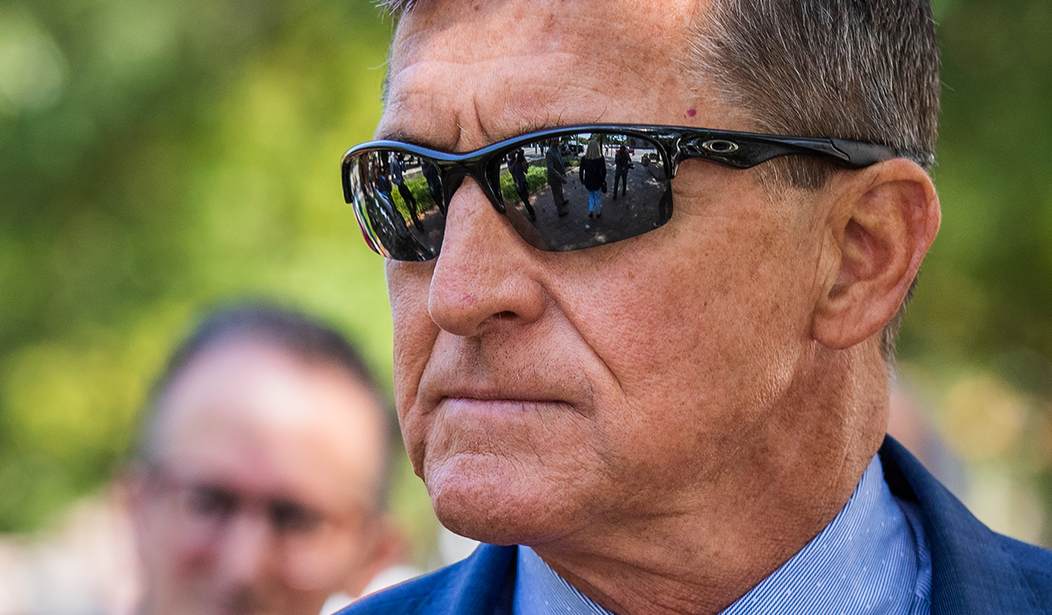

The Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia issued a decision this morning denying the Petition for Writ of Mandamus previously filed by General Michael Flynn. I gave a brief overview of the decision in this earlier story.

Through the Petition General Flynn’s counsel had sought an order from the Circuit Court directing Judge Emmet Sullivan to grant the motion to dismiss filed by the government, which Judge Sullivan has resisted doing up to that point.

At the time the Petition was filed, Judge Sullivan had appointed retired Federal Judge John Gleeson to serve as “amicus” counsel for the purpose of briefing an “opposition” to the government’s motion. He had also scheduled a hearing on the motion, with an extensive briefing schedule for the parties to follow.

In what certainly looks like a mistake now, with the benefit of hindsight, that hearing would have taken place on July 16 – six weeks ago – and the outcome likely known by now.

Even though the briefing of the Petition and much of the time arguing the issues before the Appeals Court dealt with the proper standard for resolving a Rule 48(a) motion to dismiss, and how much discretion Judge Sullivan possesses in reaching his decision, the Opinion today is nearly silent on that question.

The decision turns almost exclusively on two points having to do with the lack of “irreparable harm” that either party will suffer if the matter remains with Judge Sullivan until he issues a decision.

First, that the delay in resolving the case does not inflict the type of “irreparable harm” to a criminal defendant such as General Flynn that requires mandamus relief to avoid. The Court pointed out that some criminal defendants remain incarcerated– suffering much greater harm — when similar types of motions are pending decision before a trial court.

While we recognize the gravity of the burdens imposed on criminal defendants, those burdens, without more, generally do not suffice to bring a case within mandamus’s ambit. See In re al-Nashiri … noting “the bedrock principle of mandamus jurisprudence that the burdens of litigation are normally not a sufficient basis for issuing the writ”… Roche … observing that the “inconvenience” of a “trial . . . of several months’ duration” and its corresponding costs “is one which we must take it Congress contemplated in providing that only final judgments should be reviewable” in criminal cases). And here, it bears noting, Petitioner is not in confinement pending resolution of the proceedings in the District Court.

The Court held that General Flynn retains other avenues of relief for any adverse outcome that might result from Judge Sullivan’s ultimate decision. Judge Sullivan might grant the government’s motion, and no further proceedings would be necessary. If Judge Sullivan denied the motion, such a decision could be subject to collateral challenge or a new petition for mandamus. The problem for the Appeals Court is that at Judge Sullivan has done neither at this point, and there is no case law that supports the position advanced by General Flynn that an appeals court should step in via mandamus and direct a trial court on how it must rule on a motion the district court has yet to decide.

Second, with regard to the potential harm and “separation of powers” issues raised by the Government, the Court held that all those claims are speculative at this point. Judge Sullivan hasn’t actually conducted any proceedings that harm the government or could be said to constitute a violation of “separation of powers” concerns. The Court stated that should that eventually happen, the Government itself could file a Writ of Mandamus, and raise the issue of what Judge Sullivan has actually done.

The Court makes a point of highlighting something that I always thought was an issue, and that I could not understand why General Flynn’s counsel and the government had not addressed it. After Judge Sullivan appointed amicus counsel and set a schedule for briefing and hearing the government’s Rule 48(a) motion, neither party raised an objection to either order. Such an objection would have forced Judge Sullivan to better explain on the record the steps he was taking, and any Order issued by him denying the objection would have been an Order that could have been taken up on Mandamus. But that state of the record before the Appeals Court is simply that Judge Sullivan set a schedule for the hearing, and appointed amicus counsel. Rather than challenge the propriety of both, General Flynn’s counsel went straight to the Circuit Court with it’s mandamus petition. That tactical decision was noted in today’s decision.

The Court also noted that the Government had not filed the writ seeking relief, yet the original panel decision granting the Petition had focused almost exclusively on the claimed harms the government asserted in its brief filed in support of General Flynn’s petition.

The Majority opinion states that it is not necessary to resolve the issue of whether the harm asserted by the Government, as a party who had not sought relief, was appropriately considered by the three-judge panel, as it finds that the harms asserted by the government don’t satisfy the requirement that they be “irreparable” – primarily because at this stage the alleged harms are all speculative. Judge Sullivan hasn’t yet compelled the government to do anything as part of his decision-making on the motion to dismiss that might be deemed a “separation of powers” problem. Until he does so, there is nothing for the Appeals Court to review.

The Court distinguished its earlier decision in Fokker Services on the different procedural posture of each case at the point in time where the Circuit Court was asked to intervene via mandamus. In Fokker Services the district court had denied the Government’s motion to dismiss – something Judge Sullivan has not yet done, and might never do. The Court held that the harms that might come as a result of such a denial are speculative at this point because they might never arise if Judge Sullivan ultimately dismisses the case without any searching inquiry into the decision-making processes of the Government. The Court AGAIN notes that the Government did not raise these objections before Judge Sullivan, and put him in the position of having to defend his intentions which the Appeals Court might have then reviewed.

Quite simply, the only separation-of-powers question we must answer at this juncture is whether the appointment of an amicus and the scheduling of briefing and argument is a clearly, indisputably impermissible intrusion upon Executive authority, because that is all that the District Judge has ordered at this point.

Frankly, as a strictly legal matter, it is difficult to challenge the Circuit Court’s view on this issue. It is easy as a commentator to claim to know what Judge Sullivan is likely to do based on his conduct and comments to date, but saying what he will actually do is an exercise in “predicting the future.” Because of the nature of the distinctive roles played by the trial court and an appeals court, this is a practice that cannot be indulged without disrupting the way the two courts function together as part of a whole.

The dissent seeks to debate the metes and bounds of separation of powers depending upon how the hearing might actually unfold, but “[a] fundamental and longstanding principle of judicial restraint requires that courts avoid reaching constitutional questions in advance of the necessity of deciding them.”

That passage is the point around which the majority is able to rally itself without sending any signal to Judge Sullivan that his approach is being validated by the Court’s decision. The caution to Judge Sullivan is that, while he hasn’t done anything yet to warrant intervention, the Court is not suggesting the path he seems to have staked out is free of obstacles. In fact, the Court “invites” THE GOVERNMENT to return to the Court with its own mandamus petition if concrete steps infringing on “separation of powers” concerns actually happen.

Regardless of the exact form the proceedings take below, these developments underscore the point that a petition for mandamus filed in anticipation of a district court argument is almost invariably premature.

….

Nothing in this decision forecloses the possibility of future mandamus relief should the District Court’s disposition of the motion to dismiss or other order violate the separation of powers or some other clear and indisputable right. We need not and do not now pass on the issues that might be presented by such a mandamus petition; it suffices that no such petition is before us, and that the ability to seek mandamus at the appropriate time (if necessary) provides “[an]other adequate means to attain the relief,” …. such that the writ may not issue now.

The Court also declined to order that the case be reassigned to another judge. The Court noted that judicial decisions handed down by a judge are almost never sufficient, by themselves, to justify removal. Such decisions are always subject to appeal. Further, the Court found that all the comments made by Judge Sullivan amount to comments by him based on his review of the evidence in the case. Such reactions by a judge do not constitute impermissible “bias.” Judges are expected to develop opinions about cases as they review and consider evidence in the case, so comments by the judge that reflect a point of view based on the evidence do not reflect an improper bias justifying removal. “Bias” must be based on something other than what the judge learns about the case during the course of presiding over it.

The majority did, however, include a sentence at the very end that I have never seen in an appellate decision before, and there is no other reason for the sentence other than to send a subtle message to Judge Sullivan.

For the foregoing reasons, the Petition for a writ of mandamus is denied. As the underlying criminal case resumes in the District Court, we trust and expect the District Court to proceed with appropriate dispatch.

I read that as a modest rebuke of what Sullivan has done to date and the manner in which he has handled the matter since the filing by DOJ of the motion to dismiss. It’s a not-too-veiled expression of disapproval. Had Sullivan acted with “dispatch” to this point, there would have been no need to include the admonition. It is an overt recognition that all can see Sullivan engineering events in the case to satisfy personal interests in the outcome.

What the Court avoided doing altogether was to take any position on the substantive issue regarding the scope of a district court’s discretion to deny a Rule 48(a) motion. The opinion is silent about what action(s) by a district court would intrude on exclusive executive authority so as to create a possible “separation of powers” problem. The issue remains entirely unaddressed by the majority opinion, and no clarity is provided to the district court on what it may or may not do in its deciding the pending motion.

But what the broader Court membership also did — in my opinion — was to rebuke Judge Rao, one of the newest members of the Court, for writing an extremely broad majority opinion for the panel. Judge Henderson, who was the senior judge in the majority on the panel, and therefore assigned the opinion to Judge Rao, probably did her no favors by not forcing her to pull back some on the scope of her decision. Her status as one of the newest members of the Court, and the fact that her opinion really pulled the Court’s jurisprudence far down the “separation of powers” path with regard to how Rule 48(a) motions should be addressed, set her up to be second-guessed by the Court as a whole, especially given its ideological makeup. Judge Wilkins on the panel showed there is clearly a sentiment among more liberal members to allow district court judges to “probe” the thinking of the government in seeking to dismiss cases. It should not be surprising that other judges of similar ideological dispositions would agree with Judge Wilkins, and that they would be inclined to not let Judge Rao’s decision be the final word for the Court on the subject.

Counsel for both Gen. Flynn and DOJ should now request an immediate hearing. All the issues have been briefed, including by the Court and by the amicus. The motion has sat in the District Court now for nearly 90 days. Judge Flynn’s motion to withdraw his guilty plea has been pending even longer. Seeking an immediate hearing would force Judge Sullivan to state his intentions on how he proposes to review the motion — whether by way of an evidentiary hearing with witnesses from DOJ, or otherwise. The parties should push Judge Sullivan to address the motion on the merits and force him to quickly document any intention at further “game-playing” with regard to either further briefing or a scheduling a hearing. It is up to the parties to establish what constitutes “dispatch”, and force Judge Sullivan to comply.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member