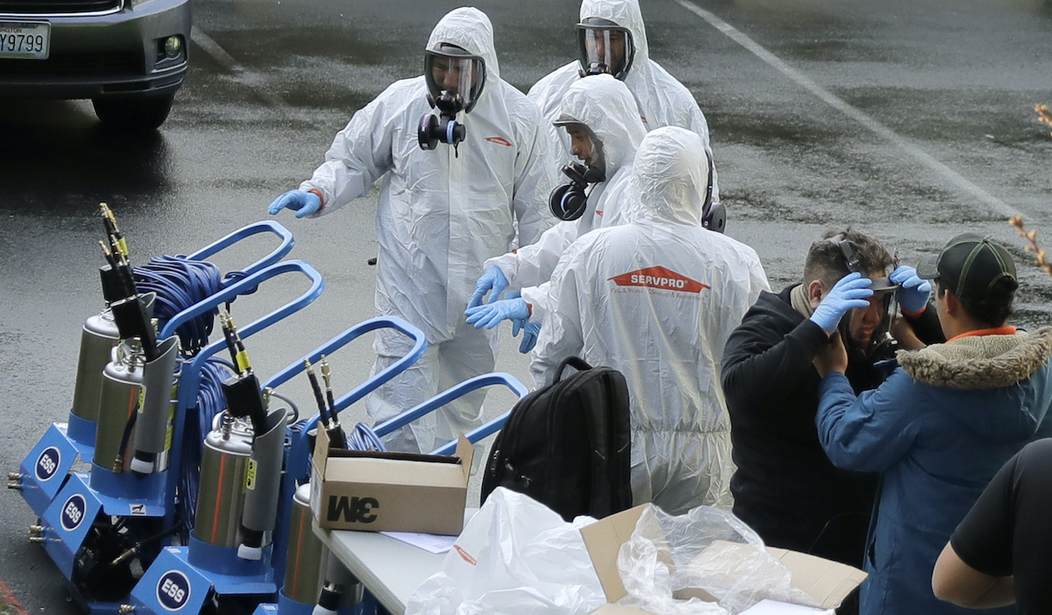

Workers from a Servpro disaster recovery team wearing protective suits and respirators more toward equipment as they line up before entering the Life Care Center in Kirkland, Wash. to begin cleaning and disinfecting the facility, Wednesday, March 11, 2020, near Seattle. The nursing home is at the center of the outbreak of the COVID-19 coronavirus in Washington state. (AP Photo/Ted S. Warren)

Many a news story will be written — and has been written — about how the government failed to stockpile enough mechanical ventilators to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic. Whether that’s because the media latched on to this narrative because machines are easy to understand, or because it somehow thinks that ventilators are the only issue, the sad fact is that the media is missing the larger story in this pandemic.

President Trump has referred to this as a war. Imagine going to war and knowing you need to get supplies (food, ammunition, medicine, etc.) to the front lines. You buy 1,000 two-and-a-half ton trucks from General Motors. But, the darned things aren’t made by Tesla and won’t drive themselves. So now you have 1,000 trucks sitting idle while you train up 1,000 men to drive them. That’s what this pandemic has exposed: we do not have enough skilled clinicians who deliver respiratory patient care at the bedside or enough monitoring equipment to assist them. There is a woefully insufficient number of trained respiratory therapists out there to manage patient ventilators. Even if there were enough trained and experienced respiratory therapists to handle this pandemic, there is insufficient monitoring equipment available to support patient monitoring prior to and after intubation and ventilation.

In an ICU environment, the ventilator is one — among many — pieces of life support technology. There are IV pumps, cooling mattresses, and suction equipment in an ICU. There are chest-drainage systems in the event a patient develops a pneumothorax. But most importantly, there are pieces of equipment that provide early warning of impending disaster: pulse oximeters and end-tidal CO2 monitors. The pulse oximeter is an ingenious tool that uses two or more wavelengths of light shining through the skin, and a pressure measuring device called a plethysmograph, that measures arterial pressures. Usually, these devices are clamped on a finger and can give doctors a readout of a patient’s oxygen saturation. Some, like Masimo’s SET system, also provide measurements of carboxyhemoglobin, methemoglobin, and offer indexes to both oxygenation and perfusion. These are vital tools necessary to monitor patients on ventilators. While arterial blood gases are still the gold standard for determining oxygenation and ventilation, a pulse oximeter is the single most valuable tool in the ICU because it gives the staff a window into both oxygenation and perfusion.

So ubiquitous have pulse oximeters become, that no ICU could get insurance without them. While the media is listening to a New York governor whine about ventilators, it is completely missing the boat on the issue of patient monitoring. If you have a 16 bed ICU and all 16 beds have ventilators, most hospitals will run out of ventilators pretty quickly. But once outside of the ICU, there is no centralized monitoring except in step-down units. Even there, the pulse oximeters may not be networked into the alarm system. As a result, a patient who is not on a ventilator, but may be heading that way, can’t count on being monitored for developing trends because he will only be “spot-checked” for oxygen saturation; the networked monitors that provide trend information are all on the ventilated patients.

By focusing on ventilators to the exclusion of monitoring tools, the government has done a disservice. As shown by Boris Johnson’s recovery in the UK, not every patient will require mechanical ventilation. Some will respond to aggressive oxygen therapy and pulmonary hygiene measures. But you can’t know who will and who will not by looking at them. You need monitoring equipment and clinicians skilled enough, and with enough experience, to interpret the monitoring data and intubate if needed. This means one-on-one time with a respiratory therapist, and plenty of experienced respiratory therapists managing the patient in response to the patient’s oxygen and ventilation status.

Sadly, this isn’t something that nurses can be trained to do in a pinch because the management of these patients is based on experience, and without experience in seeing patients at the bedside, specifically as it relates to their breathing, a clinician is likely to miss important signs. But because of short-sighted government reimbursement in healthcare, and a general belief that all those ventilators would never be needed, the government chose to focus solely on the mechanical ventilators and not on the status of

the patients or the providers taking care of them.

While I am not of a mind to support a 9/11 type commission looking into the response, I am interested in seeing someone evaluate the planning for this pandemic and making changes necessary to secure our response to the next one. That planning should involve not only the doctors who write orders for ventilators, but the therapists and nurses who carry out patient monitoring and patient care in and out of the ICU. Too many people have been left out of the planning process. That needs to change.

*Anthony L. DeWitt, RRT, CRT, Attorney at Law

Before pursuing a career in law, Tony DeWitt was a respiratory therapist and

department manager at several different hospitals. He is now an attorney with the law

firm of Bartimus Frickleton Robertson Rader in Jefferson City, MO.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member