Because the overwhelming majority of people never run for office or even serve any time in elective office, their understanding and perspective on politics are governed by a lack of real-world, on-the-ground knowledge, understanding, and experience of how politics works.

So, let me light a candle to illuminate things rather than simply curse the darkness. We hear and read a lot lately about the idea of political loyalty. A sort of unspoken but understood quid-pro-quo — I scratch your back, you scratch mine. Fair enough. Nothing inherently wrong with that.

However, it’s worth understanding that in politics, there’s no such breed of animal called a Loyalist. In the political jungle, where everything is rough and tumble, it’s eat or get eaten. It’s kill or get killed. You can call it nasty, you can call it whatever you want, but you might choose to simply call it zero-sum.

At the risk of being presumptuous, we’ve all heard the phrase “All is fair in love and war.” Well, you can add politics to that equation: All is fair in love, war, and politics since politics is war by other means.

I want to share with you an important concept. And despite its logical elegance, it might seem complex or perhaps counterintuitive. So stay with me.

Just as in economics, where supply or production creates demand, we refer to this supply-side economics principle as Say's Law (named after political economist Jean-Baptiste Say [1767-1832]), so too is it in politics. The overwhelming majority of political candidates don’t begin their campaign with voter demand. Instead, they start by supplying ideas and positions on issues, which creates political demand. And sometimes it doesn’t.

I say the overwhelming majority of candidates don’t start with demand because, as with everything, there are exceptions. Some candidates do start with voter demand. Think Colin Powell, Oprah Winfrey, The Rock. In California, in the early 2000s, Arnold Schwarzenegger, who won his race for governor by 17 percentage points, started his campaign with tremendous demand before anyone had the slightest idea what he stood for.

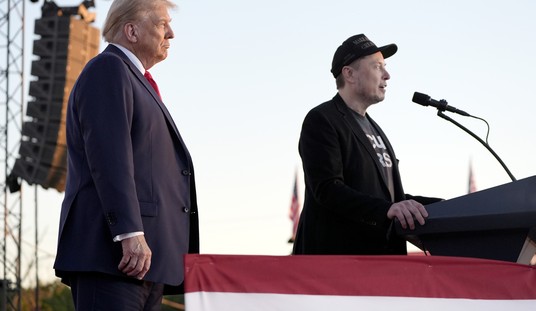

Donald Trump provides us another example of Say's Law in politics. In 2015, there was little to no political demand for Donald Trump’s candidacy for president. That is why he was trailing in most of the national polls in 2015 and even into early 2016. It wasn’t until he laid out his supply of ideas and unconventional positions, with disciplined repetition, that a demand for a Trump presidency really caught fire.

Similarly, in 2018, there was no political demand for Ron DeSantis to be governor of Florida. Much of the demand for that (not all of it) was essentially created when Donald Trump endorsed him in the Republican primary. We can debate as to when and why he rose in the polls; still, it’s reasonable and fair to acknowledge that demand for a Governor Ron DeSantis was mostly nonexistent before he was endorsed by Donald Trump. And even then he managed to only win in the general by a fraction of a percentage point, or 32,463 votes.

However, in 2022, things changed, and Governor DeSantis no longer needed anyone’s endorsement to fuel demand for his reelection. After four years of a steady production of stellar policy results, tremendous demand from the voters vaulted him to a reelection victory by a shocking 19+ percentage points, or 1.5+ million votes.

This gets us back to my essential point:

For those attacking DeSantis running for president in 2023 as somehow an exercise in disloyalty, they are ignoring the tenuousness of political demand or political capital. But if you think of political capital the way you think of financial capital, you can perhaps appreciate that, like financial capital, unless you lend it or invest it, it can rapidly lose its value. Political time waits for nobody.

So, whether you support him or not, there’s no doubt that DeSantis entered the 2023 presidential race with significant demand based on what most conservatives describe as a remarkable production of political successes and public policy victories.

Americans love winners. And DeSantis, before he found himself on the wrong side of $30 million of negative ads on TV and relentless ad-hominem attacks on social media, was considered a winner. And in politics, winners win, and losers, well, losers tend to lose. That is another law of the political jungle, but perhaps that's a column for another day.