[You can read Part 1 of this incredible and appalling but, sadly, totally true story here.]

One Man, Five Stories, Zero Credibility

Putting Bill Browder’s story on film was a natural decision for Andrei Nekrasov. A well-known and respected member of the international human rights community who already had a history of making documentaries exposing the regime’s lies and militarism, the abuses occurring in what he sadly called “Putin’s Russia” occupied and sickened the talented Russian film-maker.

At the beginning of his film, The Magnitsky Act – Behind the Scenes, he tells us that Browder’s story of Magnitsky’s imprisonment, torture, and brutal murder “deeply shocked me and I knew one day I’d make a movie about it.” But, as he was filming, Nekrasov began to notice—almost against his own will—that some things in his script just weren’t making any sense.

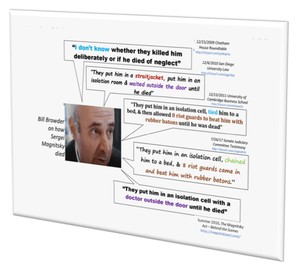

In March of 2012, while lobbying Congress to pass the Magnitsky Act, Browder had testified about Magnitsky’s death. He told them that a couple of Russian cops named, Artem Kuznetsov and Pavel Karpov—after eleven months of inflicting constant degradation and torment on the poor man—finally came to understand that Sergei Magnitsky was so pure of heart as to be unbreakable.

And so, on the night of November 16, 2009:

The put him in an isolation cell, chained him to a bed, and allowed 8 riot guards with rubber batons to beat him for 1 hour and 18 minutes until he died.

But, while filming a reenactment of this harrowing scene, Nekrasov found that he had trouble even fitting eight men with batons into a room the size of an isolation cell; which got him to wondering about Browder’s story aloud with his film crew.

Why would it take an hour and eighteen minutes for eight riot guards with batons to beat a gravely ill man chained to a bed to death?

Why would eight trained riot guards with weapons even bother to chain down an unarmed and mortally ill prisoner before administering their beating?

At that point, various problems with Browder’s account of Magnitsky’s imprisonment and death that Nekrasov’s intense empathy had pushed aside crept back to center-stage to unsettle him.

In an interview shot in the summer of 2010, [shown at 30:40], Browder had told Nekrasov a quite different story in which Magnitsky had been intentionally denied treatment so that he would perish from natural causes. No baton-wielding riot guards made an appearance nor was he beaten or even restrained; and the only constant was that hour and eighteen minutes that Browder somehow knew it had taken Magnitsky to die:

He went into critical condition on the night of November 16 [2009]. He was yelling that someone was trying to kill him. They put him in an isolation cell for one hour and eighteen minutes with a doctor outside the door, until he died.

Of course, neither President Obama nor anyone in congress can be faulted for being unaware of a story Browder told that only became public four years after the Magnitsky Act was signed into law.

But it turns out the episodes covered in Nekrasov film are far from the only times Browder has changed his tune.

And, shockingly, most of the different versions were told before Browder’s testimony and were easily discoverable if anyone had bothered to even cursorily investigate before passing a law irreparably damaging relations between the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals based on a story by a man who traded in his US citizenship to avoid paying a fraction in taxes on an enormous pile of money he’d acquired buying valuable shares of Russian industries at low prices because the common folk to whom they were issued didn’t know they were worth more than a bottle of vodka or a few slabs of pork.

At a December 6, 2010 conference at the University of San Diego School of Law—15 months before telling the House of Representatives that Sergei Magnitsky had been chained to a bed and beaten to death by 8 riot guards—Bill Browder can be seen on video claiming, instead, that Magnitsky was purposefully mistreated and neglected till he became mortally ill and then left alone for one hour and eighteen minutes to die of natural causes while his tormentors waited outside his cell.

Like the story he’d told film-maker, Andrei Nekrasov six months earlier, there was no beating by eight riot guards with rubber batons or anyone else. However, unlike the version Nekrasov had heard, in this telling Magnitsky was put in a straitjacket.

Almost exactly a year later on December 13, 2011, Browder was interviewed by the University of Cambridge Business School, again on video, and the rubber-baton-wielding riot guards who three months later played such an important role in his testimony to Congress made what seems to be their first appearance.

However, no handcuffs were yet used nor was the straitjacket from the year before hauled out.

This time, Magnitsky was tied to the bed.

Yet, two years earlier, on December 15, 2009, while speaking at a round table discussion at the London policy institute, Chatham House, Browder didn’t know exactly how Magnitsky died or even whether he was killed intentionally!

I don’t know what they were thinking. I don’t know whether they killed him deliberately on the night of the 16th, or if he died of neglect.

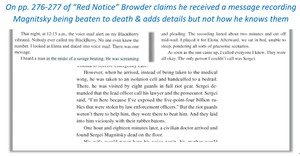

Magnitsky had been dead for less than a month. So you might think that Browder simply hadn’t yet discovered any of the details of the quite different stories he would later go on to tell. However, if his 2015 book, Red Notice, is to be believed, not even Browder’s earliest discrepancies can be justified.

You see, on pages 276-277, Browder claims that on the night Magnitsky died, a message recording a portion of his fatal beating was left on his voicemail!

I heard a man in the midst of a savage beating. He was screaming and pleading. The recording lasted about two minutes and cut mid-wail… I called everyone I knew. They were all okay. The only person I couldn’t call was Sergei.

The sensational voicemail message isn’t the only part of Red Notice that reads more like a Robert Ludlum novel than real life. And Browder never says who sent it or why.

But even Robert Ludlum wouldn’t write a story in which a deathly ill, agony-stricken man imprisoned and tortured for eleven months and finally chained to a bed while eight riot guards finish him off with rubber batons suddenly finds himself in possession of a phone and manages to leave a message on his boss’s voicemail.

So presumably we’re supposed to think this extraordinary audio was sent to our protagonist by the evil Russian authorities as a warning. That’s certainly how Robert Ludlum would have written it, in any event.

But, if Bill Browder is to be believed, truth must still be stranger than even the most unrealistic fiction since Ludlum certainly wouldn’t have had the message slip his protagonist’s mind less than a month later. And he might have had his hero at least release the audio to verify his fantastic story, something Bill Browder has, for some reason, neglected to do.

In his book, Browder goes on to tell the same story of Magnitsky’s demise involving chains and eight rubber-baton-wielding riot guards that Congress heard but with the additional details that when they entered his cell, Magnitsky “demanded the lead officer call his lawyer and the prosecutor” and told them “I’m here because I’ve exposed the five-point-four billion rubles that were stolen by law enforcement officers.”

But these details weren’t part of the Ludlumesque phone message, which began while the beating was already in full swing and only included Magnitsky screaming and pleading in an anguished unrecognizable voice.

So, one wonders both how Browder could know about Magnitsky’s opening remarks to his executioners and, more generally, how all the august legislative bodies and human rights advocates to whom he’s told versions of his story could have failed to question from where the details of whichever one they happened to be hearing could have possibly come.

Questions Only an Idiot Could Fail to Ask & Answers Only a Bigger Idiot Could Possibly Accept

The Chatham House roundtable isn’t the only time this unforgettable phone message seems to have, nonetheless, somehow slipped Bill Browder’s mind. Apart from his book, he appears to have never once mentioned it in any of his other recitations of Sergei Magnitsky’s fate. In fact, Browder has changed his story about where he’s getting his extraordinary details almost as much as he’s changed the details themselves.

Sadly, however, not with any increase in plausibility.

At the 2010 San Diego Law conference cited above—immediately after telling his audience about straitjacketed Magnitsky dying sans riot guards, rubber batons, or beating, with the Russian authorities who planned his death, instead, sadistically but tastefully waiting outside the door—Browder explained:

The reason that I know the details of his situation is that while he was incarcerated, he wrote 450 complaints in his 350 days of detention.

Though the stories of how Magnitsky died are completely different, this is somehow the exact same explanation Browder gave in the House of Representatives two years later of how he knew Magnitsky was chained to a bed and beaten to death by eight riot guards.

Immediately after providing these ghastly details, Browder testified:

How do we know all this? We know it because Sergei did something very unusual. He documented it all in 45O complaints in his 358 days in detention. And as a result of that, we have the most well-documented human rights abuse and extrajudicial killing case in the history of Russia.

But, on the off chance you’re as inattentive to the obvious as the United States Congress when they pass earth-shattering legislation ramping up tensions with powerful adversaries, how is it even remotely possible that Magnitsky managed to write and submit a complaint during his final 78 minutes among the living while chained to a bed and enduring a savage beating by eight riot guards armed with rubber batons?

Or, in case you like the less sensational Stanford version of the story better, how did Magnitsky write and submit his complaint while dying alone and in agony from intentionally-induced natural causes in a straitjacket while those responsible waited outside the door?

And, even if Magnitsky somehow managed to get a hold of a pen and paper, scribble down the details, either while straitjacketed or chained and savagely beaten, and slip his note to a clever rat he’d spent his time in prison training to deliver his final message to the world, how did he know it would take 78 minutes for the guards to murder him or for his illness to finish him off, again, depending on which of Browder’s stories you like best?

Moreover, even had Magnitsky somehow managed the miraculous task of writing and submitting a complaint minutely describing his predicament and predicting to the minute exactly how long it would take to kill him, no matter the version of his story you prefer, it’s still not clear how Browder could have ever seen it or any of the other complaints Magnitsky wrote since, while being deposed under oath by a company he’d accused of laundering some of the stolen $230 million in New York, Browder denied ever once having consulted with Magnitsky’s lawyers or even knowing whether anyone on his team had.

This is another claim, by the way, which is contradicted in Browder’s book; several times, as a matter of fact.

Nor is it anywhere close to the only statement Bill Browder made while under oath that completely contradicts central parts of the allegations that caused congress to pass the Magnitsky Act.

As a matter of fact, it turns out that Bill Browder was very reluctant to testify under oath at all. One of the few comical episodes in Andrei Nekrasov’s otherwise darkest of films occurs when he discovers a video of pudgy, middle-aged, seemingly mild-mannered, Bill Browder violently knocking aside pedestrians, diving into his limo through one door, fleeing through another, and running down 51st street in New York after a Daily Show appearance in an ultimately futile attempt to avoid the subpoena.

But we’re not finished listing all the different stories Browder has told about how Sergei Magnitsky died and our final entry is of particular importance.

In a Russian language interview from June 2011, Browder gave another explanation of his extraordinary fly-on-the-wall knowledge of Magnitsky’s final hours; also telling yet another variation of his death scene in which no beating occurred but—in what surely must have represented excessive precautions on his murderers’ part—both a straitjacket and chains were used to restrain the mortally-ill and agony-stricken prisoner.

At long last, however, someone finally had the good sense to at least ask how he knew about that damned straitjacket.

Upon which Browder claimed the information had come from a report by an outfit called the Moscow Public Oversight Commission.

***

Believe it or not, Congress and President Obama’s criminal dereliction of duty in buying Bill Browder’s preposterous fairy tale is a whole lot worse. Be sure to check out Part 3:

“Congress Cites a Report That Directly Contradicts Every Single Assertion It’s Supposed to Corroborate“

***

Join the conversation as a VIP Member