The topic of jury nullification is an interesting subject that gets very little attention. But if it was used more often, it could move us closer to a society that values and protects liberty.

A recent case in Houston demonstrates how jury nullification can work when the government is trying to enforce what the residents perceive as unjust laws. On Thursday, Houston prosecutors will either have to dismiss or reschedule a case against volunteers working with Food Not Bombs, an organization that has been targeted by the local government for feeding the homeless.

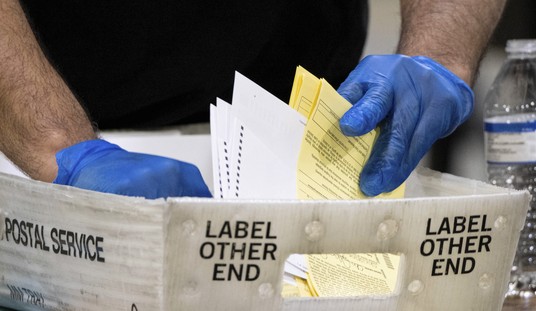

Fifteen Houstonians called for jury duty filed into a courtroom Thursday afternoon. They were there for an unusually high-profile case for municipal courts, known for hearing traffic violations and facilitating weddings.

Three of the 15 would be selected to decide the outcome of a case alleging that a woman had violated Houston law by feeding the homeless without the city's permission.

Roughly an hour later, the jury pool filed back out — all 15 of them. The lawyers had been unable to fill an unbiased jury.

Too many of the potential jurors said that even if the defendant, Elisa Meadows, was guilty, they were unwilling to issue the $500 fine a city attorney was seeking, said Ren Rideauxx, Meadows' attorney. A few jurors were also struck because they could not stay late that afternoon to serve on a jury.

The busted jury panel illuminates the potential difficulties the city could face in enforcing its controversial law through a jury of peers. Roughly 90 tickets have been issued since March to volunteers with the loosely organized Food Not Bombs, which serves meals to people in need near Central Library. The city has yet to win a single case. The one case that reached a verdict was decided for the plaintiff. City attorneys have repeatedly asked for the other cases to be reset, according to the defendant's lawyers. On Thursday, two other cases against Food Not Bombs volunteers were dismissed, said Remington Alessi, who represented the volunteers, because the city had not filed responses to motions.

In an emailed statement, City Attorney Arturo Michel said that because a dismissal was in response to complaints of delays, there was "nothing to read into the dismissals regarding strategy, policy decisions, or an overall view of the cases by the judiciary." He did not mention whether he intended to refile and did not comment on the failure to assemble a jury panel.

This scenario seems to be more common than it might seem. Wade Smith, a criminal defense attorney, told the Houston Chronicle that “busted” panels happen quite frequently.

"A lot of times, a jury will nullify the law while thinking they followed it. Because they're interpreting the facts and the law in a way to get to a verdict that they feel they can be proud of," he said. "At the end of the day, the jury has to decide: Is this guy a criminal, or is he a good neighbor? I could see the jury saying, 'This guy is a good neighbor.'"

Jury nullification occurs when one or more members of the jury decide not to vote to convict a defendant of an offense, even if they believe they actually violated the law. It typically happens when jury members believe the law under which the defendant is tried is unjust or unfairly applied. It can happen in all kinds of cases – even those involving drug use.

Former prosecutor and current Georgetown University Law Center professor Paul Butler has dubbed another variation on this theme to be “jury nullification 2.0”. He used this term in reference to the case of Touray Cornell, a Missoula, Montana man charged with possession of 1/16th of an ounce of marijuana in a county that had passed a citizen initiative instructing law enforcement to make marijuana enforcement their lowest priority. Of 27 potential jurors questioned during voir dire, only five said they would vote to convict a person of possession of such a small amount of marijuana. Skeptical that it would even be possible to seat a jury, the judge in the case called a recess during which time the lawyers worked out a deal known as an “Alford plea” in which the defendant didn’t admit guilt.

When these kinds of rejections of enforcement of laws stack up over time, the laws become unenforceable. We’ve seen this rejection of the Fugitive Slave Laws and alcohol prohibition, for example, undermine such laws’ enforcement. Eventually, it is no longer worth the time or hassle or embarrassment for government officials to try to enforce these laws. They may be further nullified in a sense either remaining on the books but not being enforced or being repealed altogether.

In this case, it appears the jurors made the right call. The notion that the government should be empowered to take $500 from a resident simply for feeding the homeless is absolutely absurd. Prosecutors are not protecting anyone’s rights by prohibiting volunteers from offering food to homeless individuals.

Perhaps jury nullification should become even more common. With all of the laws our governments place on us, there is certainly room for resisting those that are unconstitutional or immoral. Imagine if we had more people who were willing to do the same against governments seeking to convict citizens for violating COVID-19 restrictions? What if there were people who could do the same for the J6ers who were unfairly convicted of crimes?

There are many weapons we should be using to fight for liberty. Jury nullification can be one of the most effective if enough of us are willing to use it.