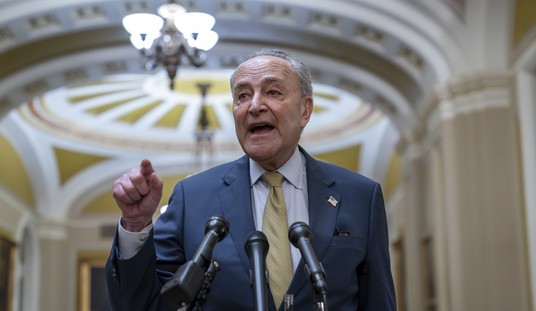

Federal prosecutors Sam Buell, far left, and Andrew Weissmann, center, smile as they talk with reporters outside the Federal Courthouse after winning their case against Arthur Andersen in Houston Saturday, June 15, 2002. A jury on Saturday convicted Arthur Andersen of shredding Enron-related documents, dealing the company a huge blow and giving a first victory to prosecutors investigating Enron’s collapse. (AP Photo/David J. Phillip)

Washington investigative reporter John Solomon reveals that a mere two weeks after the Special Counsel’s appointment, over-zealous prosecutor Andrew Weissmann, made a bold but secret offer to the American attorneys for Ukrainian oligarch Dmitry Firtash. According to Solomon, the essence of the offer was: “Give us some dirt on Donald Trump in the Russia case, and Team Mueller might make his 2014 U.S. criminal charges go away.”

In 2014, Firtash was indicted by the Chicago U.S. Attorney’s office on bribery and corruption charges in India related to a U.S. aerospace deal. The indictment followed a 13-year DOJ investigation. Firtash has remained in Austria for the past five years as he fights extradition to the U.S.

Solomon writes that details of this never before reported offer were confirmed to him by “multiple sources with direct knowledge, as well as in contemporaneous defense memos” he has read.

The timing of this news couldn’t be better, given that Robert Mueller is expected to testify before two House committees on Wednesday.

Although there is nothing extraordinary about a prosecutor offering a deal to the subject of an indictment, Solomon’s sources have said this particular “overture was wrapped with complexity and intrigue far beyond the normal federal case.”

First, several days before the offer was made, FBI agent Peter Strzok had sent the text heard around the world which said, “there’s no big there there.” This text indicates that, two weeks in, investigators had no “smoking-gun evidence against Trump in the Russia case because the Steele dossier — upon which the early surveillance warrants were based — was turning out to be an uncorroborated mess.”

At the same time, Solomon wrote:

Key evidence [against Firtash] was falling apart. Two central witnesses were in the process of recanting testimony, and a document the FBI portrayed as bribery evidence inside Firtash’s company was exposed as a hypothetical slide from an American consultant’s PowerPoint presentation, according to court records I reviewed.

In other words, the DOJ faced potential embarrassment in two high-profile cases when Weissmann made an unsolicited approach on June 4, 2017, that surprised even Firtash’s U.S. legal team.

Next, even for Weissmann, the overture was thought to be “audaciously aggressive.”

Firtash’s attorneys shared several memos with Solomon which provided details about Weissmann’s communications with their team. One memo indicated Weissmann had claimed they could “resolve the Firtash case and neither the DOJ nor the Chicago U.S. Attorney’s Office could interfere with or prevent a solution, including withdrawing all charges. The complete dropping of the proceedings … was doubtless on the table.”

Firtash’s attorneys were skeptical of Weissmann’s authority to make the charges go away. Mueller was a special counsel, as opposed to an independent counsel, which meant he answered to the Attorney General.

Finally, Firtash’s attorneys were surprised by “how much Weissmann communicated to them about his hopes for the Ukrainian oligarch’s testimony.” Solomon explains:

Prosecutors in plea deals typically ask a defendant for a written proffer of what they can provide in testimony and identify the general topics that might interest them. But Weissmann appeared to go much further in a July 7, 2017, meeting with Firtash’s American lawyers and FBI agents, sharing certain private theories of the nascent special counsel’s investigation into Trump, his former campaign chairman Paul Manafort and Russia, according to defense memos.

For example, Firtash’s legal team wrote that Weissmann told them he believed a company called Bayrock, tied to former FBI informant Felix Sater, had “made substantial investments with Donald Trump’s companies” and that prosecutors were looking for dirt on Trump son-in-law Jared Kushner.

Weissmann told the Firtash team “he believes that Manafort and his people substantially coordinated their activities with Russians in order to win their work in Ukraine,” according to the defense memos. And the Mueller deputy said he “believed” a Ukrainian group tied to Manafort “was merely a front for illegal criminal activities in Ukraine,” and suggested a “Russian secret service authority” may have been involved in influencing the 2016 U.S. election, the defense memos show.

Weissmann’s private observations and sharing of prosecutor’s theories went beyond what prosecutors normally do in proffer negotiations and risked planting ideas that could lead the witness to craft his testimony, according to legal experts I consulted.

Firtash’s attorneys told Solomon they had rejected the offer because their client simply did not have “credible information or evidence on the topics Weissmann outlined.”

As mentioned previously, Firtash has been fighting extradition to the U.S. from Austria for five years and last month, an Austrian court ruled against Firtash.

Firtash’s team has taken the fight up a notch. They have now presented information about Weissmann’s offer to the court as potential defense evidence that the DOJ’s prosecution is flawed by bogus evidence and political motivations. According to Solomon:

In a sealed court filing in Austria earlier this month, Firtash’s legal team compared the DOJ’s 13-year investigation of Firtash to the medieval inquisitions. It cited Weissmann’s overture as evidence of political motivation, saying the prosecutor dangled the “possible cessation of separate criminal proceedings against the applicant if he were prepared to exchange sufficiently incriminating statements for wide-ranging comprehensively political subject areas which included the U.S. President himself as well as the Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Austrian officials suddenly reversed course last week and ordered a new, lengthy delay in extradition.

That new court filing asserts that two key witnesses, cited by the DOJ in its extradition request as affirming the bribery allegations against Firtash, since have recanted, claiming the FBI grossly misquoted them and pressured them to sign their statements. One witness claims his 2012 statement to the FBI was “prewritten by the U.S. authorities” and contains “relevant inaccuracies in substance,” including that he never used the terms “bribery or bribe payments” as DOJ claimed, according to the Austrian court filing.

That witness also claimed he only signed the 2012 statement because the FBI “exercised undue pressure on him,” including threats to seize his passport and keep him from returning home to India, the memo alleges. That witness recanted his statements the same summer as Weissmann’s overture to Firth’s team.

Somehow, after witnessing the FBI’s treatment of General Michael Flynn and others, it’s not difficult to believe they would engage in such heavy-handed tactics.

Additionally, the Firtash team presented “evidence of alleged prosecutorial wrongdoing.” A key document provided by the DOJ which they claimed was proof of Firtash’s guilt was actually “created by the McKinsey consulting firm as part of a hypothetical ethics presentation for the Boeing Co. and had no connection to Firtash’s firm.”

Moreover, McKinsey claims in an official statement that it had no knowledge of a bribery scheme by Firtash, and the PowerPoint’s use of the phrase “bribery payments” never came from Firtash or his company and were, instead, hypothetical “assumptions by McKinsey about standard business practices in India,” according to the new Austrian court filing.

Firtash’s attorneys told Solomon they had informed Weissmann about this document in 2017, however, he minimized its importance and never notified the Austrian court. “The document was never withdrawn as evidence, even after the New York Times published a story last December questioning its validity.” One of Firtash’s attorney wrote to Solomon:

Submitting a false and misleading document to a foreign sovereign and its courts for an extradition decision is not only unethical but also flouts the comity of trust necessary for that process where judicial systems rely only on documents to make that decision. DOJ’s refusal to rescind the document after being specifically told it is false and misleading is an egregious violation of U.S. and international law.

Firtash’s experience with Andrew Weissmann, although unethical, is not a bombshell. Nor is it a surprise. It is simply one more questionable act in Weissmann’s long history of improper prosecutorial misconduct.

Still, it should be brought up during Mueller’s testimony on Wednesday to show the American people how Weissmann operates and just how politically driven and corrupt the Special Counsel investigation has been.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member