My father was a very funny man, full of quiet humor, optimism, and play. But he could become quite serious, too.

When I was a little boy learning his rules of life, Dad had a saying, “Right kind?” When he looked me straight in the eyes, stuck out his hand, and asked that question, I knew an extremely important time had come.

Forget anything I had said before, that was the very last moment I could change my story to The Truth, if necessary.

If I looked at him straight back, said “Right kind,” and shook his hand, I better be telling The Truth because that sealed the deal forever.

I’m sure I did come clean at times before saying his phrase, though I do not remember.

I honestly don’t know what would have happened if I had lied. I never asked. I was too afraid. Honor and trust seemed so important to him. And I never wanted to violate that.

What I do remember still, after his passing and all these decades, is that telling the truth is of paramount importance. I make no claim of perfection. But I carried that belief into journalism. And I thought others did, too.

Turns out, it was easy to cheat in journalism. We had notebooks, pens (with backup pens), and pockets laden with dimes for pay phones. I confess that at a few major news events, I rendered the occasional pay phone inoperative by removing an important part. That way, after the event, I could replace the piece and always have phone access to send in my story.

Cellphones were nonexistent then. Radio reporters had tape recorders. Those devices betrayed my blind trust twice over the years and left me feeling like the doomed Titanic lookouts when the iceberg suddenly emerged from the North Atlantic darkness.

In those days, you scribbled notes in your own shorthand. If a quote was important, you’d check it with the subject. At times, I phoned newsmakers after writing a story. Just to double-check quotes with them, not provide access to the whole story.

That was also insurance against later complaints to editors.

I wrote a major story about the surrogate mother controversy. I talked to many women directly, both proponents and critics. So readers would feel the compelling power of both sides: the couples who desperately wanted a baby, the women who helped them, and those who found borrowing a womb immoral.

It led the paper on a Sunday. Next day, one female reporter said, “I could never have written that story that way.” I took it as a compliment, but later realized it was an honest confession.

I assumed my northeastern colleagues were liberal. We talked political stories, but not politics. They expressed surprise twice — when I left after 26 years to work for a governor and when they discovered he was Republican.

So, recent and ongoing revelations of journalistic dishonesty are sickening personally. They have totally and properly demolished trust in our vital media. In a recent survey, Gallup found trust in media at an historic low. Most of us know that without polling.

This isn’t surprising anymore. But it is dangerous for the long-term viability of a functioning democracy when voters lack access to reliable sets of facts. Or media provide only selective information that supports their agenda.

The Founding Fathers gave media special constitutional protections because of their essential role as government watchdog and purveyor of a common set of facts.

Newspapers in the late 19th century were basically a party press with facts being only convenient tools to make partisan arguments.

I’ve likened the 20th century’s monopoly newspapers to pharmacies where a class of editors, cloaked in titles, chose the subjects and versions of what they deemed the day’s important or interesting events to deliver to readers as their daily dose of news.

The Internet’s arrival destroyed that monopoly and created a multi-headed media dragon whose priorities were to attract the maximum online clicks offering fare that might be important and could be true.

That dumped responsibilities back on the news consumer. As Russell Crowe’s “Gladiator” screamed at the blood-thirsty crowd in the Coliseum, “Are you not entertained?”

Part of this, I believe, dates back to the Watergate days of the 1970s. That was an historic exposé that revealed the secret, illegal political undertakings of the Nixon administration. All worthy watchdog work by the Washington Post, with others following.

Unfortunately, too many young people were attracted to journalism then, not so much to tell compelling stories that illuminated life in our common society, but to "fix" society, whatever that meant and took. And hopefully to be not the old-fashioned, working-class, shoe-leather reporter, but to become celebrated stars like Woodward and Bernstein, the primary Watergate reporters.

At roughly the same time, major journalism institutions came under mounting pressures to boost minorities and women in their ranks, perfectly reasonable improvements.

But in the haste to meet their own racial and gender quotas, many of these institutions shortened or even eliminated training.

My generation sought to become reporters in the 1960s. Many of us spent several years as copyboys and clerks, learning the skills of reporting, absorbing the standards of objectivity, accuracy, and culture of the institution, while writing on our own time to practice and gain recognition.

One egregious example was Jayson Blair of the New York Times. In less than four years, he went from intern to star national reporter. Then, following reader complaints, a Times investigation found “widespread fabrication and plagiarism” in scores of his stories, and he resigned in 2003.

Janet Cooke of the Post won a 1981 Pulitzer Prize for a touching feature story about the life of an inner-city youth who, it turns out, did not exist.

The newer generation of journalists was dissatisfied with traditional objectivity and wanted to cause change and make a difference, whatever that took and how they saw it.

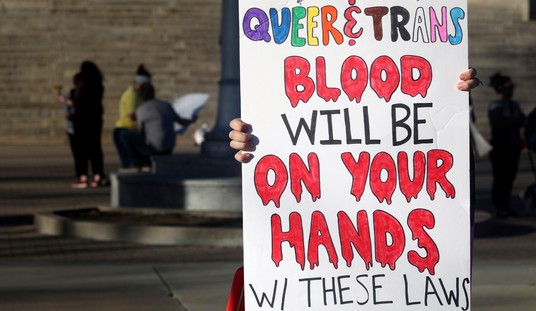

Examples of that bias, distortions, and the poison of newsrooms’ Woke culture are too numerous to list, especially during these later days of a heated presidential campaign.

Just recently, CBS News, once considered the gold standard of TV news, was caught editing its taped interview of Kamala Harris to make her sound better, meaning less like herself. And refusing to release the actual transcript. Possibly igniting a government inquiry.

Despite all the liberal talk about the importance of diversity in everything, media joined with Biden agencies in a conspiracy to suppress online conservative news, including here at RedState.

They successfully pressured social media to adjust algorithms accordingly, which reduces revenues and the financial viability of media that doesn’t follow accepted narratives. So, targeted media had to develop alternative sources of income.

Government and industry cooperating for social control used to be called fascism.

Prime example was two years of dismissing and ignoring the Hunter Biden laptop story, buying the Biden campaign and intelligence community claim it was Russian disinformation. It wasn’t. But such suppression helped Democrat election outcomes.

Perhaps you saw the FBI report this year that violent crime was down 2.1 percent nationally in 2022. That became a helpful Democrat campaign talking point, obediently and eagerly mirrored in widespread media reports.

ABC News’ David Muir got himself in credibility trouble by contradicting Donald Trump’s debate statement that crime was up.

But then, a conscientious RealClearPolitics did some digging and discovered the FBI had stealth-edited its crime statistics. Violent crime in that year actually increased 4.5 percent.

Trump was correct. But Muir's false correction was already circulating, as intended by Democrats.

CNN’s Candy Crowley laid the same stunt on Mitt Romney during a 2012 debate to the benefit of Barack Obama.

Now, we learn the Bureau of Labor Statistics pulled a similar trick recently, belatedly admitting it had cooked new job reports by adding 800,000 jobs that were not actually created.

Humans make mistakes. But all of these strangely seem to benefit the same political party.

Until Joe Biden’s nationally televised debate disaster in June, Democrats, along with sympathetic media, helped hide his worsening mental and physical condition. Which could reasonably be considered a national security concern.

But they have been all over Donald Trump for perceived grievances, even suggesting the Pennsylvania assassination attempt was staged.

During his first term, the Post kept a running daily count of alleged Trump lies, mounting into the thousands. For some "reason," the Post has not undertaken a similar conscientious count of Biden’s copious untruths that he continues to spout even when proven false.

Normal news consumers do not have the time to personally fact-check everything they read or hear. They have relied on and been betrayed by media operatives like Muir, who only “fact-check” details that don’t fit their partisan narrative agenda.

I have long held that media cannot tell people what to think. They can, however, tell Americans what to think about. And by malicious omission what not to think about.

So, we have been blanketed in recent weeks with coverage of Harris’ campaign of “joy,” but not so much about the emptiness of her policies.

Given the media’s record in recent years, I’m not sure I can trust their report that the presidential race is historically close. Not by accident, this would keep news consumers paying close attention, which is good for business and falsely gives one candidate a better standing than deserved.

However, such a claim is, by necessity, based on polls, which are based on what respondents tell pollsters, which might be true.

I confess I have no idea how media can restore trust. As important as it is to the proper functioning of a democracy, at the moment, that appears impossible. I doubt they even see it as a problem. That’s another problem.

The only reliable recourse now, it seems, is to crowdsource that trust or mistrust. Leave it to individual news consumers to leverage their media use; despite temptations, don’t patronize sites or networks that betray our trust. Share that choice.

And hope that over time the collective market impact of that lost business forces improvements. When I entered journalism, my father offered the wry observation: “Isn’t it amazing how every day just enough news happens to fill the newspaper?”

If he was here now, I imagine him sticking his hand out to media and asking, “Right kind?” Sadly, we know what their honest answer would have to be.