For refugees, peace is something that happens briefly between periods of stark terror.

They squat on the roadside, feet filthy in broken sandals, eyes empty, faces averted. Their belongings are few. Most were abandoned on their long flight from fear. Or stolen at gunpoint by armed marauders. Comfort to these lost souls is a foreign word. Hoping seems dangerous. They try to forget sights they’ve seen. They have no idea where they’re going.

The scenes you see these days on TV of refugees in Afghanistan or Syria or anywhere convulsed by war are truly awful. Innocent people terrified into silence, abandoned by decency and hope in conflicts driven by angry men they’ve never heard of with important agendas that encompass no little people.

So many have gathered around Hamid Karzai International Airport in the last two weeks that the crowds are visible from space. But, honestly, the terrible scenes of death and fear and children lost to families are nowhere near the truth on-site.

The actual scenes are much worse, far worse, so much worse, in fact, that media too often don’t say or show all of it. A refugee shot in the face because he had nothing to give a government deserter. That’s a truth. But do you want to see that tomorrow at breakfast just before the chipper weatherman?

Remote controls in hand, we can only imagine how bad it really is in the broiling heat, searing fears, and swirling scary rumors within the crowds around and inside the airport in Kabul these long days. They’re desperately seeking to escape somewhere — anywhere — from the needless, deadly chaos of ruthless new rulers and Joe Biden’s botched troop withdrawal from Afghanistan, his troop redeployment back into the country, and now, another troop withdrawal that threatens to leave some Americans behind.

But I need not imagine what it was like in Vietnam in the closing days of that last lost war of 1975 when people became refugees within their own country. I was there.

The United States, convulsed by years of anti-war protests, race riots, assassinations, and government lies, had withdrawn its troops in 1973. After 13 years, the national patience finally expired over a bloody foreign war with inept leaders and no end or goal in sight, as the relentless communist insurgents knew it would.

We flew into Cam Ranh Bay from Saigon in early morning. It was a beautiful place, a natural, deep-water harbor where so much war materiel flowed through. But now it was in abandoned tatters.

The chartered plane circled the harbor. Amazingly, it was full of ships crammed with people — about 9,000 it was estimated, covering every inch of decks.

These were refugees from Danang, some 300 miles north. Kurt Oltmeyer was captain of the Andrew Miller, an ancient Liberty ship turned commercial carrier. He’d been instructed to stay in international waters as fighting raged throughout Danang.

But he saw thousands of refugees huddled on the beach and remembered another disobedient captain in 1940 who maneuvered near a Dutch beach to rescue him and many others from the advancing Nazis.

“Now, I have my turn to help somebody,” he said.

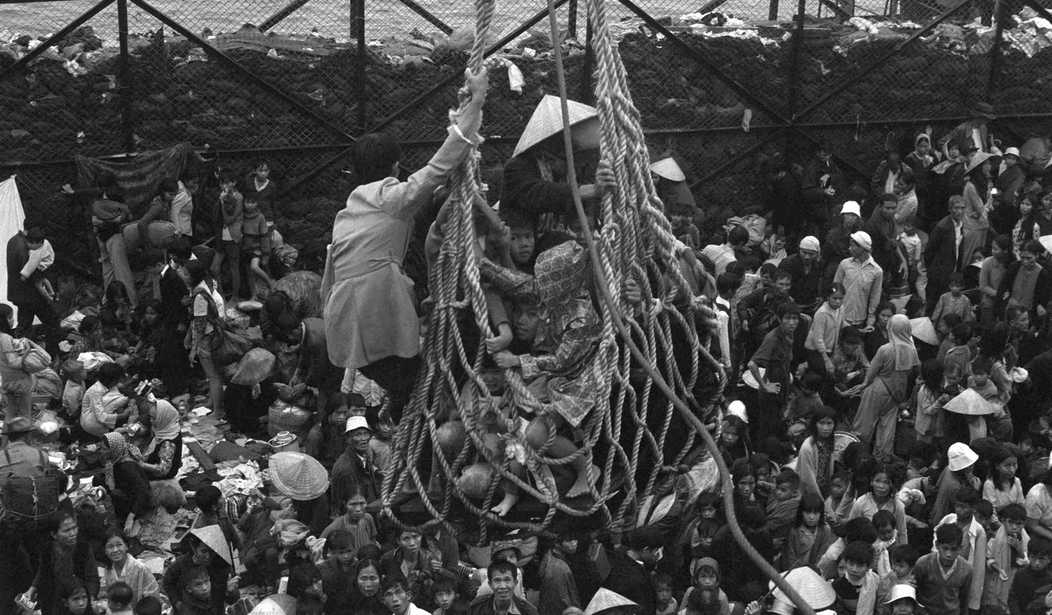

So, he eased into the harbor, opened entries. Thousands climbed, swam, fought onboard. So many, in fact, that no one could move on deck jammed standing up for two days. People fell off, screaming. Some died in the heated crush. At least four mothers gave birth standing up. If the babies survived, they’d be American citizens, born on a U.S. vessel in international waters.

As they streamed off the ships in Cam Ranh Bay, the captain gazed at a deck ankle-deep awash in human waste and litter.

Thousands milled around the docks, including dozens of lost little children. They did not know their family names. They just kept looking for a familiar face. Many were barefoot on the hot cement or wore sandwich bags for shoes.

One little girl seemed unaffected by the crowds and trucks and chaos surrounding her. She played quietly, drawing in the dirt with a stick. Where would she live now? she was asked. She did not know.

Was she worried? No, she replied calmly, her mother would take care of her. The little girl gave me a darling smile. Then she vomited in the dirt.

Within those refugee hordes was Nguyen Xuan Ngon and 10 family members. They awakened one morning near Danang. Everyone in the neighborhood was running away. Men with guns lurked everywhere. Should they hide from whatever was coming? Or flee their home for the fourth time in eight years?

They fled, but were experienced enough to know that time what to bring and what to leave. Artillery boomed in the distance. For days they trekked south in a human stream along Highway 1. The heat and noise were too much for the baby. He died.

What to do? Step off the road for a simple burial and a little service that would ensure the child’s entry into Heaven, but risk armed men catching up to the survivors? Or just bury the baby and continue running, keeping other family members alive for now but living with the baby’s wandering soul in their heads forever?

They fled. And I never saw them again.

Later that month, I was in Guam, standing on the tarmac of Andersen Air Force Base next to a line of B-52’s no longer bombing North Vietnam. Remember those daily war news about “Guam-based B-52s pounding suspected Communist strongholds”?

It was after 1 a.m. and one by one, an endless stream of chartered commercial jumbo jets taxied toward the terminal with some thousands of new refugees every day for weeks. Every plane window was lit in the darkness and filled with fearful faces peering out at their new refuge.

Guam was a five-hour flight from Saigon, a short hop in the vast Pacific area, but another world for the 110,000 refugees who ended up housed on that 30-mile-long island in 10 camps, including a massive tent city so large it got its own Zipcode.

Guam and an area of the Pacific Ocean the size of the United States was overseen by an admiral named G. Stephen Morrison, a soft-spoken naval pilot from Georgia who bombed these islands in World War II, then flew off of and commanded carriers during Vietnam. He commanded the fleet involved in the Gulf of Tonkin incident at the war’s start and had three children, including Jim, lead singer of the Doors.

A wise, organized military executive, Admiral Morrison saw a refugee exodus coming three weeks before it arrived. He had thousands of cots flown in from storage, field kitchens set up, security gates and fences erected. Besides its B-52’s, Guam is home to a naval air station and a base where nuclear subs change crews after 90 days lurking beneath the sea.

Unlike some general officers today, Morrison was ready and knew the importance of public information, even in a secretive military. He held daily briefings for the battalion of news people who descended on Guam looking for “stories.” He gave the news people daily population stats, meals served, health reports. And he facilitated their unescorted visits to camps.

Reporters had access to the top officer every day. And no excuse for misinformation.

Such a system enabled Morrison to snuff rumors before they became international news, rumors like incoming refugees carrying exotic deadly diseases, including the plague. The base doctor said he was more worried about healthy refugees catching Western diseases new to them, like chickenpox.

I asked Morrison how he was handling planeloads of orphans from a war zone. “Very carefully,” he replied.

One day near the beginning of the refugee flood, Admiral Morrison asked the immigration chief how many cases his team could process in a day for onward transport to the mainland.

“About 3,400,” was the reply.

Morrison nodded, looked down at his notes of the day’s arrivals, and said, “How about 6,000?” Except the admiral wasn‘t asking.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member