Joe Biden is quietly implementing a drastic, dangerous, and many would argue naïve change in foreign policy toward recalcitrant states such as Iran and Russia.

As part of a new approach to sanctions, built more around time-consuming collaboration and consultation with allies, Biden is already easing some existing strictures with no matching quid pro quos. Some Iranians have already been removed from Treasury sanction lists with no new commitments to negotiate.

Relieving those sanctions unilaterally is intended by the Democrat president as a sign of goodwill and allied collaboration.

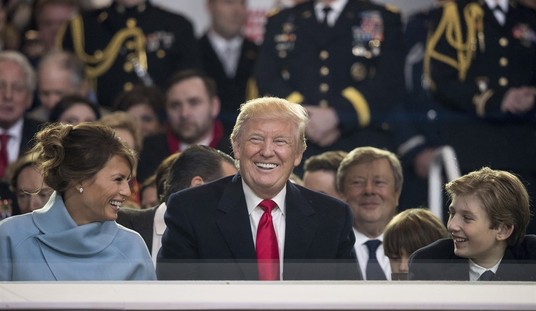

Biden clearly hopes that will lead to a renewed willingness by Teheran to engage in new talks to limit its nuclear weapons program. Also, it runs directly counter to the diplomatic strategies of Donald Trump, which is a plus in this White House.

But such relief instantly reduces the incentives to comply. And recent history by Democratic administrations suggests the goodwill is likely to be accepted willingly as just another Democrat freebie that will not be reciprocated.

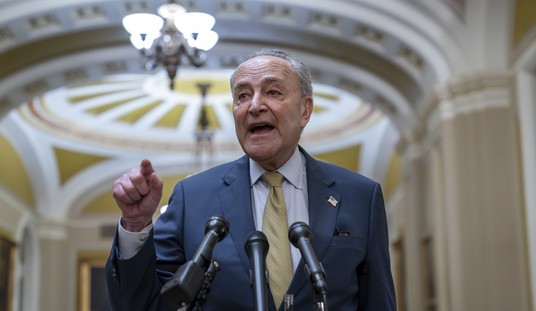

Last month, Mike Pompeo, former secretary of state, said by so eagerly seeking to revive the nuclear deal and ease existing sanctions, “the Biden administration is about to empower the world’s foremost state sponsor of terrorism again.”

When North Korea’s minute despot, Kim Jung-un, sought economic sanctions relief before meeting with Trump, the Republican refused, saying he’d first have to see concrete steps to reduce ICBM development before any relief.

Kim agreed to meet anyway – twice — at least to begin a diplomatic dialogue for the first time in any U.S. presidency.

Former Trump administration officials point out that Biden’s automatic relief squanders the pressures for changes built up over the past four years. Why should adversaries alter aggressive tendencies if waiting patiently produces the same results from a less-than-dynamic American leader who likes ice cream cones but is too eager for some kind of agreement?

It does give Biden an excuse to delay any action as he’s done now for several weeks over deciding on some retaliation for growing Russian ransomware attacks. Biden says he feels “good about our ability to be able to respond” to these attacks. But that good feeling has yet to result in any retaliatory action to discourage future attacks.

Awaiting sanction consensus to develop among allies also takes valuable time and often involves policy compromises that many feel damages U.S. national security and can appear weak and less than alert, as some of Biden’s recent military and diplomatic moves have.

The commander-in-chief last month told the nation’s military forces that the worst threat to America’s national security was not Russia, China, or a nuclear Iran that they’ve trained so hard to prepare for but it was climate change.

In 2009, when Biden was Barack Obama’s vice president, their administration unilaterally canceled an anti-missile defense system planned for Eastern Europe against any future overflights of Iranian missiles. That was intended as a goodwill gesture to Russia’s Vladimir Putin to obtain his cooperation in reining in Iran’s nuclear ambitions.

It didn’t work. Obama eliminated a threat to Putin at no cost to the Russian while getting nothing in return except a sense of betrayal among Eastern Europeans who had the rug pulled out from under them with no notice for siding with an American leader against their hostile next-door neighbor.

Putin did nothing to discourage Teheran’s nuclear ambitions. He went ahead to sell the mullahs a nuclear reactor and train their militias fighting in Syria’s civil war.

Emboldened, two years later Putin annexed Crimea from Ukraine and fomented armed rebels in eastern Ukraine. The Obama-Biden administration slapped a wide range of economic sanctions on Russia, Russians, and their institutions. Trump added more.

Nothing changed.

Which could be an argument against initiating sanctions as the opening go-to diplomatic tool to dissuade adversaries.

Sanctions are better than declaring war, of course. But with a few exceptions like South Africa in the 1990s, which gave up its domestic apartheid policies in the face of international sanctions and boycotts, such sanctions have been notable failures in recent times altering any regime’s policies.

In the early 2000s, sanctions on Libya convinced Moammar Gadhafi to turn over his entire nuclear weapons program in return for being left alone. Nine years later, however, Nobel Peace Prize winner Obama joined European powers in overthrowing Libya’s strongman, who was killed by a mob.

That allied diplomatic betrayal as a reward for relinquishing a nuclear program likely looms large in the minds of the current leaders of Iran and North Korea.

Besides Putin’s resistance, a variety of sanctions on Venezuela’s Nicolas Maduro and his team, including oil boycotts, banking restrictions, and frozen personal and government assets have yet to produce any signs of a return to democratic methods there.

Indeed, as part of his new policy direction, Biden’s team has already eased some restrictions on Venezuelan shipping, citing the need for aid to combat and ameliorate Covid’s impacts.

So, it appears Joe Biden has decided since sanctions haven’t worked, more of the same probably wouldn’t either. Not an unreasonable analysis. Try something new, which might work.

But if it doesn’t, you better be prepared to walk away. History with Democrat presidents, however, suggests they end up vainly just offering billions more up front, as Obama did with rewards for Iran signing the short-term pact to slow its nuclear program.

Would be better for Biden to apply his eased sanction policy to future persuasion efforts, since all he’s doing now is watering down existing sanctions and weakening the pressures.