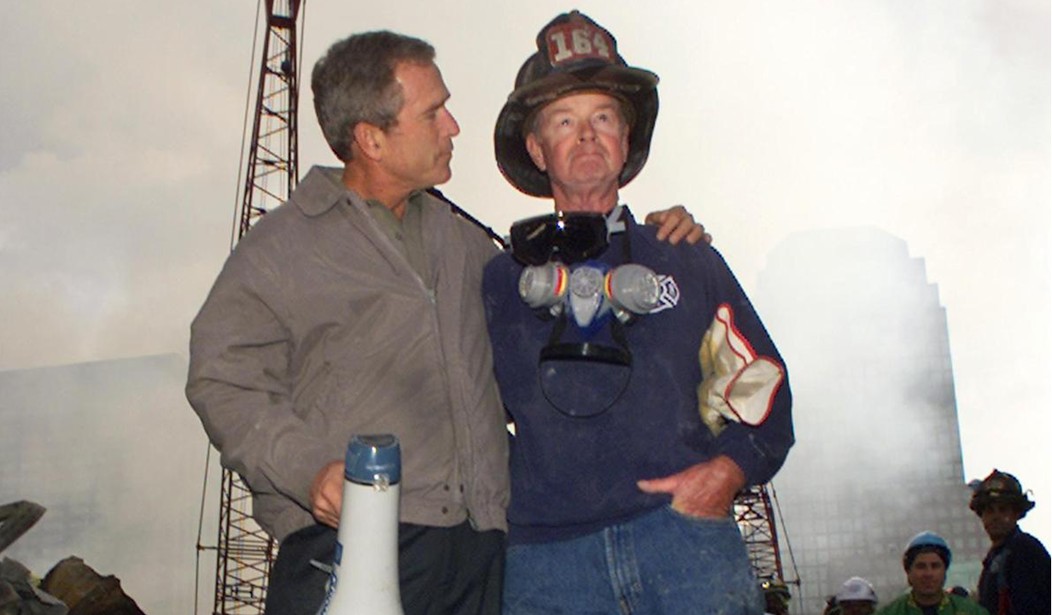

It was an iconic moment, George W. Bush at his authentic best talking to rescue workers and a shocked America from atop a heap of 9/11 rubble. Just three days after those awful sights of collapse and death the president stood there, arm around a firefighter, bullhorn in hand.

Someone yelled, “Can’t hear you.”

“I hear you!” said the commander-in-chief, “The rest of the world hears you. And the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon.” Loud cheers ensued at the site and far beyond.

The cheering has long since died, replaced by political and military exhaustion, appropriate disillusion, political opportunism, and incalculable suffering.

Less than one month after Bush’s remarks, following a night of air bombardment and Tomahawk missile attacks, the first commandos – American Green Berets and Delta Force with the British SAS — were on the ground in Afghanistan foraging for Osama bin Laden and Taliban leaders. To be followed at one point by more than 100,000 American troops and thousands more from NATO allies.

Nearly 800,000 Americans served at least one deployment in that God-forsaken land. No one knows how many suffered PTSD.

Now – 7,206 days, 3,596 allied deaths, more than 20,000 wounded, and three presidencies later – the withdrawal of the last 1,900 U.S. troops is underway, scheduled for completion by Sept. 11th, the 21st 9/11 since the first and the tenth since Benghazi.

The troops’ original goal was to destroy terrorist training camps, oust the Taliban, and capture bin Laden. The first two came easily and quickly. Then arrived the temptation to ensure that Afghanistan never became a terrorist haven again by building a new nation in a place that is not a nation.

And what has all that time, ammo, money, lives, blood, materiel, shattered hopes accomplished? “The security situation is not good,” said Gen. Austin Miller, a former Delta Force captain and the 17th U.S. commanding general there.

In fact, the security situation is awful. Maybe worse.

Like most insurgents facing superior organized armies, including American revolutionaries and Vietnamese communist guerrillas, the Taliban fade away to hiding places including next-door Pakistan. They emerge to attack only when the situation benefits them. And their commanders are not bothered by high casualties.

According to an agreement negotiated with the Trump administration, in return for allied troop withdrawal, the fundamentalists, who used to execute women for not wearing a burka, were to reduce violence, deny safe haven for terrorists, and work with the elected central government in Kabul on a coalition. They have done none of that.

Government troops see the handwriting. Morale is crumbling. Taliban forces are marching through province after province, closing in on the capital. Along the way, they murder any locals who collaborated with Americans, who as in Vietnam had no plans in place to extract to safety more than a handful of them or their families.

U.S. officials including Gen. Miller promise to support the Kabul government, which is a CYA promise that can’t happen with the planned 600 remaining U.S. troops to protect the embassy.

The U.S. complains about Taliban violations, but frustration and impatience back home with what Trump called “endless wars” has created an inexorable momentum to get the hell out asap.

As always happens even with the best American intentions, insurgents have far more patience and tolerance for deaths than American politicians or their constituents. It’s an enduring lesson the U.S. government and its taxpayers have refused to learn.

The original temptation to stay in Afghanistan is understandable, if naïve.

A quick scan of any history book would show even a millennial that no one has ever conquered, tamed, civilized, or endured long as an occupier in a space now called Afghanistan, an area slightly smaller than Texas.

Alexander the Great couldn’t do it 23 centuries ago. Sikh warriors couldn’t do it. The British couldn’t do it in the 19th century. The Russians gave up in 1989 nearly 10 years of occupation after trying to impose a sympathetic regime there.

And now comes – or rather goes — the U.S. after nearly 21 years of trying to construct a more modern society with such idealistic reforms as free votes, health care, and education for girls and women.

The reality is that despite the maps, Afghanistan is not a nation, not anything even resembling a single country. It is a wild collection of rugged feudal fundamentalist fiefdoms run by ruthless warlords whose allegiance is to self.

For more than a year now, the Institute for the Study of War has been reporting these warlords were quietly arming for the civil war they knew was coming when the foreigners give up, as they always do.

Tuesday Gen. Miller “warned” there could be a bloody civil war there. Could be?

No one is arguing the United States and Britain should remain in Afghanistan militarily or donate one more well-trained life to the good intentions of helping others there.

The fact is we stayed too long because overall Americans are by nature optimistic, hopeful, generous, and kind. And no elected politician wanted to bite the bullet and be the one to “lose” there until Trump turned an exit into recognition of reality. The enlarged mission was unwinnable from the start.

The Afghanistan War that began basically as a limited revenge operation suffered mission creep, turned inevitably into a generous but vain effort at nation-building. The likelihood that China will now move in to siphon natural resources and strategic positioning is not an argument to stay forever.

The future argument over such U.S. engagements ought to be when, if ever, the United States should commit its sons and daughters in such historically hopeless places for foreigners.

In 1954, France was losing its Indochina colony in a war against communist insurgents. It appealed to President Dwight Eisenhower for military help. He was a new president, but a veteran soldier. As Supreme Allied Commander in World War II, Ike knew a fair amount about war, mission creep, and insurrections.

He declined any U.S. involvement. The French were defeated. Indochina became a communist North Vietnam and a free South Vietnam.

But like the Taliban, the North ignored its signed commitments and horrendous casualties to infiltrate guerrillas to take over the South. In May 1961, just four months after succeeding Eisenhower, President John F. Kennedy dispatched 500 Green Berets to the South. But only to advise and train its troops, you understand.

Within a few years, however, the military mission had crept up to active combat with 1,000 times that many U.S. troops in-country. Then, by the spring of 1975 — 14 years, four presidencies and nearly 50,000 dead Americans later — the insurgents were marching through province after province closing in on the capital. Government troop morale crumbled.

The American president then, Gerald Ford, promised the Vietnam central government full support. He sent a cargo plane with 37 105mm howitzers as visible proof. I watched them unload that folly. But three weeks later, remaining Americans and a handful of Vietnamese were hastily evacuating.

Does any of this sound familiar?

Join the conversation as a VIP Member