Peace/Police Officers and Deputy Sheriffs are all basically the same thing. They are sworn law enforcement officers who are responsible for obviously enforcing the law and conducting investigations, but they're also mandated reporters, family counselors, and, more importantly, they're Fathers and Mothers, Husbands and Wives, Brothers and Sisters—human beings.

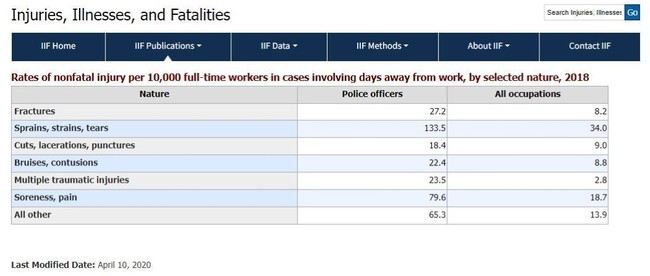

Police Officers have arguably one of the toughest and most dangerous jobs in America. According to data compiled by the Bureau of Labor and Statistics in 2018, the nonfatal workplace injuries and illnesses rate was 371.4 per 10,000 full-time workers compared to a rate for all other occupations of 98.4. Several other sources have police officers listed anywhere between the top 10 or top 25 of the most dangerous jobs in America.

The physical danger, however, isn't the greatest stressor on us. Being a police officer brings a lot more than just physical danger. It brings a massive mental health hazard to us all that tends to go unnoticed or, at the very least, hidden. There are very few professions out there that deal with the stressors that come with being a cop. Off the top of my head, the only ones that come close would be firefighters, paramedics, and medical professionals in hospitals and emergency rooms.

I was a peace officer for a little over seven years, not a long time in retrospect, but long enough to know that I have been forever changed mentally and physically. During my years on the street, working patrol, I was exposed to the absolute worst of humanity, almost the same as I saw when I was in Iraq fighting terrorists who didn't care about the rules of warfare or the Geneva Convention. Every night, I'd say goodbye to my wife; she'd tell me to stay safe, and then I'd kiss my baby boy goodbye. I'd get to work, put the uniform on, and get in my radio car (that's our term for a patrol car). My anxiety went up just a bit after logging onto my computer. I would ask myself how many domestic violence calls we would get that night, how many deuces (slang for a DUI) would be out on the streets, how many party calls would turn violent, etc.

The patrol station I worked at was a busy one. For any given day, on average, it would generate at least 600 calls for service. These ranged from report calls, which were called "routine," but sometimes these went south in a hurry. The others would be priority calls like fights, disturbances, etc., and emergent calls like assaults, robberies, shootings, etc., and finally, the others would be self-generated calls for things like traffic or pedestrian stops or investigations. In the summer months, we could easily see calls for service go well over 900 in a day.

These shifts were normally eight hours, but because we were so short-staffed that we would have to work double shifts, they were really often 16 hours. Or if we didn't have the money in the budget, we'd have to bust cars (meaning not man them), which would mean the area of responsibility for my car just doubled or tripled. There were nights when I put over 300 miles on the car because we were so short-staffed that I was going back and forth between all sides of the RD (reporting district) Map.

During these shifts, I would go to at least four to 10 domestic violence calls, and at least half of them had a legitimate victim with varying degrees of injury. Then there's the TC (traffic collision) calls where I'd see things from minor fender benders to fatal TCs with multiple ejections, bodies torn apart, and injured or killed children, I have seen it all. Then you have the shootings, where you sometimes find no victims and no suspects, or sometimes you'd find both. Bodies riddled with bullets—some lived while some didn't even make it to the hospital. Then, you might have a vehicle or foot pursuit and/or a use of force. These force incidents could range from pinching the wrist of a suspect with handcuffs (yes, that is reportable force) to a full-blown physical fight and all the way up to deadly force. I have seen and experienced it all. But then, when the unthinkable happens, and we lose one of our partners to injury or death, we have to go back to work the next day and are expected to perform our duties. We get told to take a day or two off if you need to and come back to work. We aren't afforded the luxury of taking a bunch of time to mourn the loss of a great friend and partner like the rest of society does. We have to bury that too, deep down, so we can unpack it later if we can, so we can deal with that. But we never do because we need to stay strong, we can't look weak.

Sometimes, I could experience all of that in one shift—or none of it. It was literally the luck of the draw, you could be lucky or unlucky on any given night. The average American will never experience any of this in their careers, let alone their personal lives, but the average officer will deal with that on a daily or nightly basis. Imagine the mental stress load that puts on an officer. Imagine the stress load that puts on their families, their husbands or wives, their kids? I have PTSD from my time in combat, but I can also say that it was amplified by the job.

Ask yourself, how does one go home from work after a shift filled with all that and look their spouse in the eyes after being asked how your day was? How do you answer them without scaring the hell out of them? "Hi honey, how was your day?" What are we supposed to say, "Well, sweetie, I got in a fight with an 18th Street gangster who tried to kill me, but luckily my partners saved my ass just in time?" Or should I say, "I had to play friends with the dad of a small child who he just beat to death for not eating his dinner so we could get him to make a statement that verifies what the dead kid's little sister said?" The answer: no, you don't. You never show weakness or tell them the fear that you felt after almost dying—again—because you need to be strong for them and your kids. You can't scare them with your troubles because the stress it will build over time will lead to either divorce or worse. You compartmentalize it and put it away in a box to deal with it later. Maybe because deep down, you know if you do open that box... Lord knows what will happen.

More to come in Part Two.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member