First things first: A Wall Street Journal report on Friday added new spice to the Russian collusion investigation.

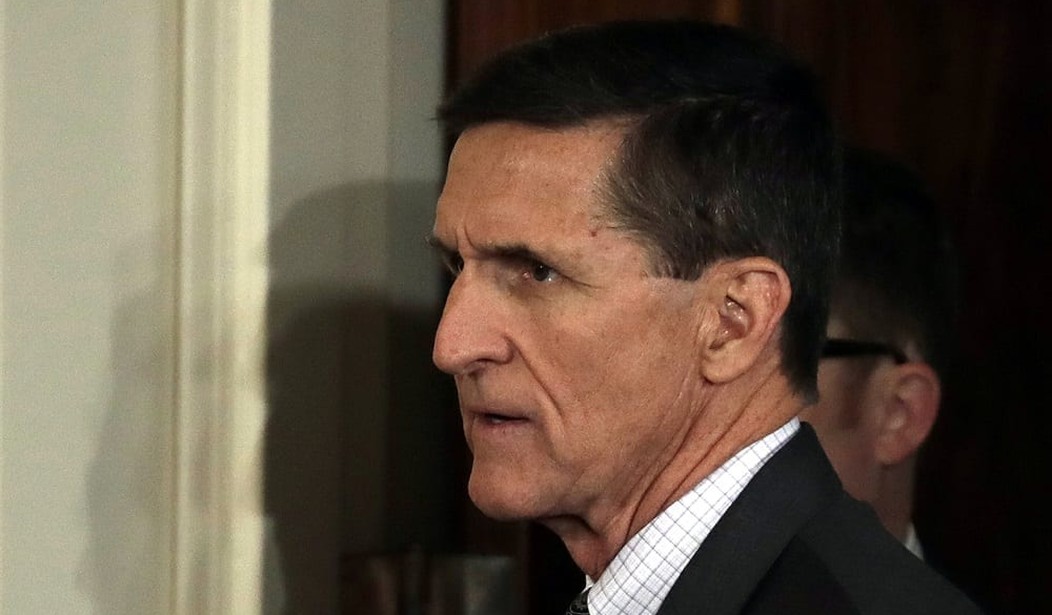

In the WSJ story, a tale unwinds of members of the Trump team working with Russian hackers, in order to get emails through a cut-out, during the Summer of 2016. Particularly, the hackers were trying to get to Michael Flynn, and a man by the name of Peter Smith was hotly working with the campaign to make that happen.

Smith turned to Matt Tait, the CEO and founder of a UK security firm called Capital Alpha Security.

In the initial WSJ story, an unnamed source was quoted about Smith’s attempts to recruit Russian hackers to go after Clinton’s emails, because, as Smith and those he was apparently working with believed, there would be something damaging in those emails that could be used.

Tait wrote for the Lawfare blog that he is the unnamed source for the WSJ story, and he goes on to explain exactly what happened, as well as why it was very concerning.

To begin, this is from the initial report:

Officials identified in the document include Steve Bannon, now chief strategist for President Donald Trump; Kellyanne Conway, former campaign manager and now White House counselor; Sam Clovis, a policy adviser to the Trump campaign and now a senior adviser at the Agriculture Department; and retired Lt. Gen. Mike Flynn, who was a campaign adviser and briefly was national security adviser in the Trump administration.

Tait made it clear that he has no dog in this hunt. As a citizen of the UK and a security specialist, his only interest was in the larger implications of Russian players tampering in the election process of another nation.

Said Tait:

My role in these events began last spring, when I spent a great deal of time studying the series of Freedom of Information disclosures by the State Department of Hillary Clinton’s emails, and posting the parts I found most interesting—especially those relevant to computer security—on my public Twitter account. I was doing this not because I am some particular foe of Clinton’s—I’m not—but because like everyone else, I assumed she was likely to become the next President of the United States, and I believed her emails might provide some insight into key cybersecurity and national security issues once she was elected in November.

A while later, on June 14, the Washington Post reported on a hack of the DNC ostensibly by Russian intelligence. When material from this hack began appearing online, courtesy of the “Guccifer 2” online persona, I turned my attention to looking at these stolen documents. This time, my purpose was to try and understand who broke into the DNC, and why.

But then there’s this:

A few weeks later, right around the time the DNC emails were dumped by Wikileaks—and curiously, around the same time Trump called for the Russians to get Hillary Clinton’s missing emails—I was contacted out the blue by a man named Peter Smith, who had seen my work going through these emails. Smith implied that he was a well-connected Republican political operative.

Tait felt Smith wanted to talk about the hack of the DNC emails, but instead, Smith was more interested in Hillary Clinton’s server, and the possibility that she could have been hacked by Russians, or anybody else. His hope was to get those emails and expose them.

Smith explained to Tait that he’d been contacted by somebody from the “dark web” who claimed to have Clinton’s missing emails. His point in contacting Tait was to determine if the emails were authentic.

Tait wasn’t convinced Clinton’s server had been hacked by Russians, but this was all going on at the same time that every U.S. intelligence agency was reporting that there was an active attempt by Russia to influence the U.S. election. He also felt that if somebody had contacted Smith through the “dark web,” that there was the very real chance that this person was part of a wider sphere of Russia’s campaign against the U.S.

Smith didn’t care.

Although it wasn’t initially clear to me how independent Smith’s operation was from Flynn or the Trump campaign, it was immediately apparent that Smith was both well connected within the top echelons of the campaign and he seemed to know both Lt. Gen. Flynn and his son well. Smith routinely talked about the goings on at the top of the Trump team, offering deep insights into the bizarre world at the top of the Trump campaign. Smith told of Flynn’s deep dislike of DNI Clapper, whom Flynn blamed for his dismissal by President Obama. Smith told of Flynn’s moves to position himself to become CIA Director under Trump, but also that Flynn had been persuaded that the Senate confirmation process would be prohibitively difficult. He would instead therefore become National Security Advisor should Trump win the election, Smith said. He also told of a deep sense of angst even among Trump loyalists in the campaign, saying “Trump often just repeats whatever he’s heard from the last person who spoke to him,” and expressing the view that this was especially dangerous when Trump was away.

Over the course of a few phone calls, initially with Smith and later with Smith and one of his associates—a man named John Szobocsan—I was asked about my observations on technical details buried in the State Department’s release of Secretary Clinton’s emails (such as noting a hack attempt in 2011, or how Clinton’s emails might have been intercepted by Russia due to lack of encryption). I was also asked about aspects of the DNC hack, such as why I thought the “Guccifer 2” persona really was in all likelihood operated by the Russian government, and how it wasn’t necessary to rely on CrowdStrike’s attribution as blind faith; noting that I had come to the same conclusion independently based on entirely public evidence, having been initially doubtful of CrowdStrike’s conclusions.

Tait went on to explain that he didn’t fully understand Smith’s connection to the Trump campaign, until he received a cover page for a dossier that would serve as opposition research against the Clinton campaign. The dossier was entitled: “A Demonstrative Pedagogical Summary to be Developed and Released Prior to November 8, 2016.” It was dated September 7.

The contact between Smith and Tait ended in September, after Smith attempted to have Tait sign a non-disclosure contract. Tait felt uncomfortable with the request – and for that matter, with the entire operation that was underway – so he refused.

The cover page that Tait got the opportunity to view, however, listed those involved in the operation.

The first group, entitled “Trump Campaign (in coordination to the extent permitted as an independent expenditure)” listed a number of senior campaign officials: Steve Bannon, Kellyanne Conway, Sam Clovis, Lt. Gen. Flynn and Lisa Nelson.

The largest group named a number of “independent groups / organizations / individuals / resources to be deployed.” My name appears on this list. At the time, I didn’t recognize most of the others; however, several made headlines in the weeks immediately prior to the election.

Tait explains that while it may seem odd that he kept quiet, until now, he did so because the Clinton emails were never uncovered, and he never had the opportunity to authenticate them, nor could he say for certain that the individuals Peter Smith was in contact with on the “dark web” were actually connected to Russia’s campaign against the U.S.

When the Journal story broke, describing how Russian hackers were attempting to get emails to Michael Flynn through a cut-out, everything suddenly seemed much more ominous, and relevant to the ongoing investigation.

Join the conversation as a VIP Member